‘Not for Glory, Nor for Wealth…For Freedom!’: The Arbroath Abbey Pageant, 1949… and a few other Arbroath pageants…

Headline image from a pageant pullout-souvenir produced in 1949

The Longest running series: On the windswept shores of the North Sea lies the UK’s historical pageant capital: the town of Arbroath. This fishing port takes the title because it has been host to no fewer than eighteen historical pageants between 1947 and 2005. It is fair to say that the Arbroath pageant experience is a long running saga rather than a simple tale of one town's pageant adventure. Unlike the vast majority of pageants, the Arbroath Abbey Pageant was not an ephemeral event, but instead was repeatedly held, although it did go through some changes over its successive runs.

The 1949 event was third in

this series. It did not prove to be the most

spectacular within the Arbroath pageant oeuvre. However, this particular production

of the pageant seems to have been when, for the organisers, pageanteering

turned from a fond act of commemoration of an ancient document, held to raise

money for a good cause, into an obsession that aimed to make an impact not only

the locally but also on a national and international scale. From this moment

on, they were on a mission! It is for this reason that it has been selected out

of all of the town’s pageants, to feature as the Arbroath contribution to our pageant

of the month. Necessarily however, a few others from the Arbroath pageant canon

must be mentioned along the way.

All the stars seemed to be aligned to create success for this pageant in the post war years. Arbroath is, from some points of view, an unpretentious town but as well as fame for its local fish delicacy, 'Arbroath Smokies', it also possessed the immense legacy of the Declaration of Scottish Independence, written in 1320 and forever associated with the town’s medieval abbey. The creation of this document was described at the time of the pageant by one newspaper as, 'the most glorious event in Scottish History'.

A Show with International Appeal: In 1949, one stalwart supporter of the pageant in its early years, the then popular historian, Agnes Mure Mackenzie, summed up the impact of Arbroath’s pageant, commenting, that it had begun as 'a burgh commemoration. By its second performance it belonged to Scotland. By its third it already transcends the national, and spreads out to the world the truth of the freedom of nations, "that no good man surrenders but with his life” ’.

Dr Agnes Muir Mackenzie O.B.E., photographed delivering the Epilogue at the 1949 Arbroath Abbey Pageant.

What did she mean? The final statement from Mackenzie’s words is of course a direct citation – taken from perhaps the most quoted segment of the Declaration. This phrase has been variously translated from its original Latin, but is often presented like this:

…for so long as a hundred of us are left alive, we will yield in no least way to English dominion. We fight not for glory nor for wealth nor honours; but only and alone we fight for freedom, which no good man surrenders but with his life.

Stirring words! And it has been ably demonstrated by historians, most notably by Professor Ted Cowan of Glasgow University, that far from being ignored and falling into obscurity in the centuries after its creation, the significance of the Declaration continued to be out and about within historical consciousness, and its words in no way forgotten by Scots – whether at home or abroad.

In the late 1940s, there was perhaps a particularly potent reason to recall the Declaration and to broadcast the sentiments it had come to embody. Within Scotland’s post war zeitgeist, there was both anxiety about the future of the world and Great Britain's place in it, as well as general unease closer to home - about how Scots themselves could or should have more of a say in their own affairs within the Union Kingdom. The big questions about what was the future of the British Empire in a world that now possessed nuclear weapons; as well as what would be the fate of the Scottish economy and Scottish governance in a unified state that through years of war had become increasingly centralised, were all lurking in the wings of the pageant arena. The pageant provided the perfect historical lens through which the troubles of the day could be filtered. Hence, by 1949, it was being claimed that this production was not just an expression of local enthusiasm for a local audience. Though, of course, all this was not necessarily at the forefront of the minds of the pageant's creators... or was it?

How it All Began: The Arbroath Abbey Pageant began in 1947 as a fundraiser for the Y.M.C.A.’s overseas’ fund. The war may have been over, but many service personnel were still stationed far from home, both in Europe and in unstable outposts of a flagging empire. Money raised was intended to fund ‘healthy’ recreational facilities for these troops. As a seaport, tourist town, industrial centre within northeast Scotland, and as the site of a naval air station, the ‘Y’ was also active in Arbroath looking after the interests of young male incomers. It was natural therefore, that Arbroath should play host to such a fundraising pursuit. A local Y.M.C.A. organiser, David Band, and some other enthusiasts got the ball rolling. The focus for the pageant was the ruined medieval abbey that dominates the local landscape, and, its most famous export – the document that also came to be dubbed, The Declaration of Arbroath because of this association.

Image of the The 'Tyninghame' copy of the Declaration [available at Wikimedia Commons: <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_arbroath.jpg>

The ‘Declaration’ was of

course first written as nothing of the sort; and instead, was a letter to the

then pope, John XXII and dated as being 'given

at the monastery of Arbroath in Scotland on the sixth day of the month of April

in the year of grace thirteen hundred and twenty'. This

particular dispatch has remained the most enduring legacy of the diplomatic

wrangle that had ensued between Scotland and England during the Wars of

Scottish Independence. Its contents have come to be regarded by many as the most

eloquently written assertion of nationhood ever produced; and as the first

example in Europe of a statement proclaiming that a monarch has a

responsibility towards his subjects, and failure to fulfil this obligation

meant that said subjects had a perfect right to get rid of the monarch. It is

these sentiments that have resulted in this diplomatic missive, morphing over

time into being described as a full-blown ‘declaration’, although this was not

part of its original intention.

The existing ruins of Arbroath Abbey showing the famous ‘round O’ window, which was a backdrop to successive pageants in the town.

The first run of the pageant in 1947 was not an episodic drama, but more of a pageant-play. It was held within the abbey ruins and re-enacted a scene that almost certainly never took place. That is, a great gathering at the Abbey of the barons of Scotland, their king, Robert the Bruce, the Scottish bishops, and the man who for much of the twentieth century was the assumed author of the Declaration, Bernard de Linton, the Abbot of the Abbey of Aberbrothnock [Abroath's archaic name]. All were depicted coming together in order to seal and send off the iconic letter. The actual historical provenance of the letter’s composition, endorsement and despatch to the pope was likely much more protracted and complicated; but the fiction thus propounded in the pageant, does not seem to have troubled the pageant's author. This was the local businessman and town councillor, F. W. A. [Frank] Thornton who was to become the mainstay of the event as pageant-master, scriptwriter and narrator for over a decade.

Thornton seems to have been

an indefatigable type; as well as owning an established drapery shop in the

town and being a civic official, he was also involved with local amateur

theatre. Although elected to the local council as an independent candidate, it

was well-known that he was a strong supporter of what was then talked of as

'home rule' or greater devolved power for Scotland within the United Kingdom.

The success of the pageant in 1947 led to the foundation of the Arbroath Abbey Pageant Society a few

months later. Thornton and others who had taken a lead in the 1947 production

would go on to be active within this and

all were determined that for as long as possible, the pageant would be an annual

commemoration.

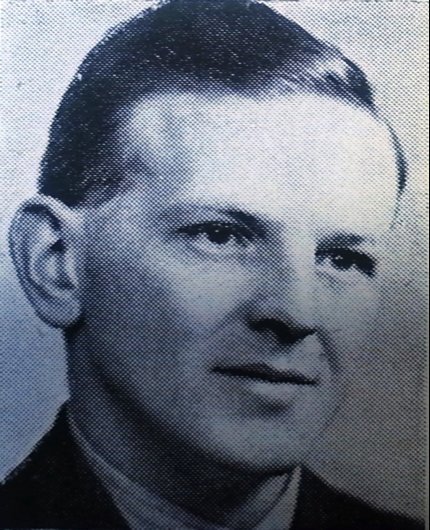

Publicity still of Frank Thornton used in 1949.

In the wake of the setting up of the Arbroath Abbey Pageant Society, it was agreed that any profits made from future pageants in 1948 and 1949 would be divided fifty-fifty between the Society and the Y.M.C.A. Thereafter this association would be severed: the ‘Y’ would need to find another outlet for its fundraising. Plain old civic acquisitiveness as well as loftier ideals about delivering an annual message to the world was at the root of this decision. Another of Arbroath's industries was tourism, and the pageant was an undoubted visitor attraction. While the Society was theoretically independent of the local town council, most of its membership were townsmen who had an interest in local commerce, and a quota of the membership were, like Thornton, elected councillors as well. Thus while the anniversary of the Declaration was in April, the pageant commemorating it would always run in high summer when Arbroath attracted thousands of tourists. The plan for the pageant following 1949 was that all profits made would be given over to the Society which would use them to ensure the longevity of the event.

Third Time Lucky: the Arbroath Abbey Pageant in 1949: The second pageant in 1948 had a slightly enlarged programme with the addition of another episode: a drama entitled The Laurel Crown, which was also written by Thornton and enacted part of the trial of William Wallace, the famous freedom fighter long garlanded in Scotland as the 'real' hero of the Wars of Independence. The event was again a success, which spurred on the Pageant Society (if it needed any encouragement) to keep going for another season.

Like its two predecessors, the 1949 pageant had three performances (on Thursday and Friday evenings and on Saturday afternoon in August). Each was fronted by a religious service and an elaborate opening ceremony spearheaded by a succession of speakers who were either politicians, decorated military heroes, or titled members of the upper classes (with occasionally all three attributes being combined in one person). In the run up to the event, numerous advertisements for hotels and boarding houses included mention of the pageant in their notices. All of which underlined the fact that by its third year the pageant had become an established week-long celebration of local culture with dances, displays and following the final show, a large historical procession through the town. In a celebration of the fishing community that was so important within Arbroath, those involved with this industry, also staged a performance of a traditional fisher wedding for the entertainment of locals and holidaymakers. In 1949, this spectacle drew huge crowds to view the wedding party as it processed through the main streets; the wedding ceremony itself took place in the town's Drill Hall on Saturday night and tickets for this were sold out. In respect of the pageant itself, the organisers conceded that obtaining a good view for the large audiences that might now be expected to attend was an imperative and for the first time a grandstand was erected within the abbey, although chairs placed around the arena and a standing enclosure continued to be utilised.

In many ways, the Arbroath pageants of 1947 and 1948 had been more clearly inspired by an older form of pageantry that was processional, stately, ceremonial, imbued with religiosity, and accompanied by sacred music. The solemnity of the occasion, the costumes of the performers (creatively manufactured despite post war austerity) and the authentic backdrop of the medieval abbey determined such spectacle as existed. There was no attempt to engage in any sort of chronological or episodic narrative spanning centuries, no action-packed battle scenes and certainly, no pagan figures from legend included. The pageant was driven by one fact of history: the Declaration and its supposed place of creation. This was a pageant that was quite simply different and proud to be so. Four decades after the birth of modern historical pageantry at Sherbourne in 1905, the Arbroath pageant managed to be both antiquarian and avant-garde in equal measure. However, perhaps somewhat bizarrely, for the third annual run and despite the huge success of the previous two years, the organisers decided to run a pageant along more recognisable Parkerian lines.

For 1949, the pageant now included a prologue, delivered in verse and written by the local poet, J. Crawford Milne. Also added were three 'ancillary historical tableaux', which were 'designed to portray important events which went into the making of Scotland's noble stand for independence'. These preceded what was now heralded as the 'main scene', this of course being the enactment of the great gathering and signing of the Declaration. The first two tableaux included a perennial staple of Scottish historical pageantry, the coming of Christianity featuring St Ninian; and following this, an episode describing the foundation of the Abbey by William I in the twelfth century. The third tableau returned to Bruce's forerunner, William Wallace and showed his last tribulation and final humiliation in London, although the actual grizzly execution of this Scottish freedom fighter was not portrayed.

The 'main scene' itself, proceeded as it had always done with the Abbot's procession into the abbey, which having made its way to the high altar was interrupted by the arrival on horseback of King Robert the Bruce. Having greeted the monarch, the Abbot and King made their way back up the aisle together followed by the King's retinue. At the altar, all kneeled to receive a benediction from the Abbot. The sacred Declaration was spread ready on a table in front of the altar and 'one by one the nobles sign' [sic] after which, each bowed to the King. The Bishops then added their signatures, and lastly, the Abbot signed the document. At the end of this ceremony, the Declaration was carried to the King and received his seal. The King and his entourage then departed the Abbey with all others making their way to the cloisters.

This ceremony was accompanied by choral music sung by the Arbroath Male Voice Choir who took the parts of monks. There was also narration given by Frank Thornton, which both described the events being enacted in appropriately solemn tone, and, at the moment of signing, in a piece of verbatim theatre, the entire script of the Declaration, as produced in a specially commissioned translation executed by Agnes Mure Mackenzie, was read out loud.

Illustration of the Declaration scene's arrangement from 1950.

Not a Mere Entertainment: The pageant organisers were always at pains to point out that their event was a reaffirmation of the Declaration, and not a trivial amusement. At the same time, they knew they had to hold the attention of the audience. The three additional episodes were clearly a concession to this. However, overall, the provision of engaging storytelling was probably less important at Arbroath than other ambitions. In the early years of the pageant, that classic troublesome duo of politics and religion had rather more of the centre stage.

Although most pageants in Scotland (and indeed across the UK) were very deferential to Christian religious beliefs and often included prayers and hymns, the general air of religiosity that surrounded the Arbroath events was even more evident than was generally found within Scottish historical pageants. Notably, at the Arbroath pageant, the audience were expected to remain respectfully silent, and there was an unwritten 'no applause' rule during the Declaration scene.' Every performance was preceded by a religious service and hymn singing, and in 1949, the introduction of a grandstand meant that a larger-scale church service on Sunday was also instituted within the abbey ruins in order to formally close pageant week. At this Sunday event, a local Church Minister stated that:

... This had been a week of pageantry, but a week of pageantry in a church... this was a house of God, and it must always be regarded as such. Our Pageant was young in years. A hundred years from now men might be celebrating it; on the other hand, it might be dead in five years' time. But the originators were wise. They decreed that each performance should open with an act of worship... should the pageant be divorced from the worship of God and degenerate into mere miming of sacred things, should these hallowed walls be desecrated by being turned into a place of mere interest and entertainment, then the pageant is doomed. Spiritually it must die. Only a spiritual impulse will keep our Pageant alive...

The historian Callum Brown has alerted us to the fact that the Protestant churches in Scotland enjoyed an almost unprecedented surge in popularity during the 1940s. The Arbroath pageant reflected this enthusiasm. Yet what the Minister did not mention of course, is that the house of God in question was once a Roman Catholic place of worship and indeed had quickly fallen into ruin post-Reformation. The Presbyterian churches therefore had good reason to assert their influence forcefully within any ceremony that took place in this iconic building. This may well have acted as a means to offset the pre-reformation reality that was yearly enacted in the pageant, where two of the central figures were Roman Catholic Bishops and where the aim of presenting historical authenticity meant that genuflection and other elements of Roman Catholic ritual were included as part of the performance.

The One Where Cultural Nationalism Met Political Nationalism and Resulted in a Pageant!: The stirring words of the Declaration could not help but be an inspiration for both separatist-nationalists and home-rule enthusiasts. Views on the political destiny of Scotland almost certainly lurked around in the background of the pageant, even if these were not a guiding force on the actual drama portrayed. Nonetheless, it was an open secret that Frank Thornton and others amongst the pageant's organisers were at the very least, home rule supporters, if not quite yet, outright separatists.

By its third staging, the pageant coalesced with a heady time in the development of the Scottish National Party (SNP). In 1949, the Party drew up the National Covenant for Home Rule and launched it at their third annual conference. Only the following year, in 1950, a group of nationalists famously removed the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey and some months later deposited it at Arbroath Abbey from where it was recovered having been placed in the guardianship of (surprise surprise!) Frank Thornton and one of his fellow town councillors. It is a reasonable supposition therefore, that the pageant may have influenced the politics of some and coalesced with the views of others who already had nationalist sympathies. Certainly, in the epilogue which was also added to the pageant in 1949 and given by Agnes Mure Mackenzie following the final performance, she ended her oration on the significance of the Declaration with the rallying cry, 'That was Scotland. And please God it would be Scotland–-Scotland yet.'

The incorporation of an additional scene concerning the martyrdom of the freedom fighter William Wallace was also grist to the nationalist mill. In 1947, members of the SNP had challenged a ban issued on them by Dundee City Council and held a 'Wallace Day Demonstration of Commemoration' in a public park in the city. In support of this act of defiance, a spokesperson condemned Dundee Council and specifically cited the case of Arbroath Town Council, which had 'backed... in every way' the commemoration of the Declaration in its first pageant that same year. This commentator went further to say that:

Wallace did not belong to any party or division of people but to the Scottish people. The Scottish National Party were holding the demonstration for no reasons of selfish party propaganda, but in order that the people of Scotland might learn lessons from the days of Wallace, and might be inspired to put them into effect... If Wallace had been on the same platform in defiance of the Town Council of Dundee, he would have felt perfectly at home...

Yet such commentary, probably inadvertently, did point up a truth, for this most popular, national historical figure was capable of symbolising directly competing political philosophies among Scots, and Wallace had equal appeal for the unionist majority.

A Pageant for all Scots? : Most Scots saw Wallace as an important figure in the creation of a Scottish national identity that was strong enough to survive and, indeed, still flourish alongside political union. The assertions of the Declaration on 'freedom' understood in this period as national self-determination within a democratic state, inspired similar sympathy. So a further element in the Arbroath pageant's success was that while it stirred patriotism, and may have influenced a few to turn to the SNP, it did not necessarily rock the steady unionist boat. Indeed, even the well-known home-rule supporter, the journalist Lewis Spence who had made an appearance at the 1948 Arbroath pageant, seemed more inclined to this stance when he wrote:

The Arbroath Declaration... should be engrossed in letters of gold and suspended on the wall of every Scottish schoolroom. Had its appeal failed, had a reinvigorated England once more attempted the enslavement of Scotland upon the death of Bruce, as indeed it did, although unsuccessfully, our country would assuredly have endured the same miseries and indignities as did Ireland until the beginning of the nineteenth century, and would have languished as a subsidiary and neglected province. But thanks to our staunch and courageous forebears, Scotland was at last enabled to arrive at a peaceful and amicable union with her larger neighbour... The two countries enjoyed an equality of partnership; one not the dominion of another...

Guided by such sentiments, by its third production in 1949, a now enlarged Abbey pageant was able to rouse the passions of Scots of all political persuasions or none, and all denominations or none, and appeal to devotees everywhere, as Agnes Mure Mackenzie highlighted, of 'freedom'. Mackenzie also commented that 'the pageant may very well make new history as well as commemorating the old... I hope Arbroath will not be so modest as to feel that one smallish burgh cannot do so very much to make history?... A few voices speaking Propter Liberatum may explode latent force that can do tremendous things – I am sure.' She clearly spoke to a receptive audience who were still living with very recent memories of their nation being imperilled. Having been a creation of a particular post-war moment, the reminder given to Scots through the pageant of how as a nation they had once stood up to tyranny, rang a peal of contemporary bells. These only rang louder the longer the pageant managed to keep going and attract attention. Yet despite its undoubted appeal to a wide audience, the suspicion that political-nationalist sentiment was somewhere in the mix when the pageant was instituted was one that stuck.

All three performances were well-attended and attracted visitors to the town. It was generally agreed afterwards that 1949 had been the most successful Abbey Pageant so far, transcending both of its forerunners. The weather was lovely over the entire week, and on a clear, balmy night on Saturday, for the first time, the organisers arranged for the Abbey to be floodlit. A torchlight procession walked to the Abbey Green, 'and as midnight approached the great concourse of people joined in singing the 23rd Psalm, and a beacon was lit in one of the tall windows of the south transept immediately under the Round O'.

What was it about this

rather solemn and (on paper at least) austere piece of drama that so moved

audiences, and fired the enthusiasm of its serial supporters? The answer lies

with the doggedness of its organisers, which in 1949 led them to make a

commitment – one which some of them likely did live to regret when the post-war

moment faded and times inevitably did get tougher for the pageant.

Photograph of the main scene in 1949 showing the Abbot of Aberbrothnock accompanying Robert the Bruce as he departs the abbey having set his seal of the Declaration of Scottish Independence.

The pageant Goes Forth: The 1949 production was the beginning of the Arbroath pageant's halcyon days. It was the final one in which the Y.M.C.A. had a fundraising stake. It seems also to have been pivotal in influencing the future composition of the pageant. Following that year's performance and now fully in charge and plentifully encouraged, the Pageant Society determined to make their commemorative performance into an annual national pilgrimage. Any pretence that the event would further adopt traditional prescriptions for historical pageantry with additional, chronological episodes was jettisoned. Arbroath went its own way in order to celebrate local culture and assert national pride – however its audience might understand this.

In every successive run, the 'main scene' remained with only a few changes being implemented within the drama. This was also always preceded by a drama on some aspect of William Wallace's demise. For those taking part, it also developed into a peculiarly male-centred annual event. The additional episodes introduced in 1949 had necessarily involved female performers; but these scenes were never repeated and appropriately perhaps for a show which had developed because of the fundraising needs of the 'Y', it returned to being very much a boy's own pursuit! A pageant for all Scots it may have been, but at the level of participation, Scotswomen would mostly stay well in the background undertaking such tasks as organising fundraising events for the Society, making costumes and providing the audience with a tea stall.

This trajectory would cause problems for the pageant in future years. Yet such traditional attitudes should not give the impression that the pageant did not innovate. The Arbroath Abbey Pageant continued its happy progress into a fourth successful year in 1950. And following this, it would virtually bankrupt itself in order to embrace new technology, which enabled spectacular Son et Lumière shows to be held during the early 1950s.

The pageant and its main subject – the Declaration of Scottish Independence – provided a perfect scenario for the assertion of Scottish identity and for pride in being Scottish that appealed to a slowly growing number of separatist-nationalists but equally to what was then the ‘unionist-nationalist’ majority. It was also a platform to extol the virtues of 'freedom', as the Iron Curtain well and truly descended. Over its first decade, the Arbroath Pageant provided something of a barometer of wider influences on Scottish society: the religious influence steadily declined as part of the show, but accusations that it was a vehicle for SNP supporters and, occasionally, for anti-English sentiment, rose.

Pageant fatigue eventually set in. The sheer slog of organising an annual run caused some disillusionment and the halcyon days of the pageant came to an end in the mid-1950s. The tenth Arbroath Abbey Pageant in 1956 and its financial failure caused the organisers to decide to take a break. Since then, the Pageant Society has resurrected the performance a further eight times, most particularly, for the 650th anniversary of the Declaration, which occurred in 1970. And in more recent productions, women have stepped more into the limelight. The last major performance was held in 2005, but on the basis of past revivals, this almost certainly will not be the last. A remake is likely overdue.

Despite the failure to maintain the momentum of the pageant, interest in the Declaration has not declined and the long run of pageants and the influence this has had on many of its thousands of spectators has almost certainly played a part in this. More information about the Declaration and its possible international dimensions, provided by Professor Ted Cowan, as well as some nice views of the Abbey and clips from of a later enactment of the pageant, can be found in this short film available online at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UChGq43b_lM

Linda Fleming