The Sherborne Pageant 1905

‘The Mother of All Pageants’

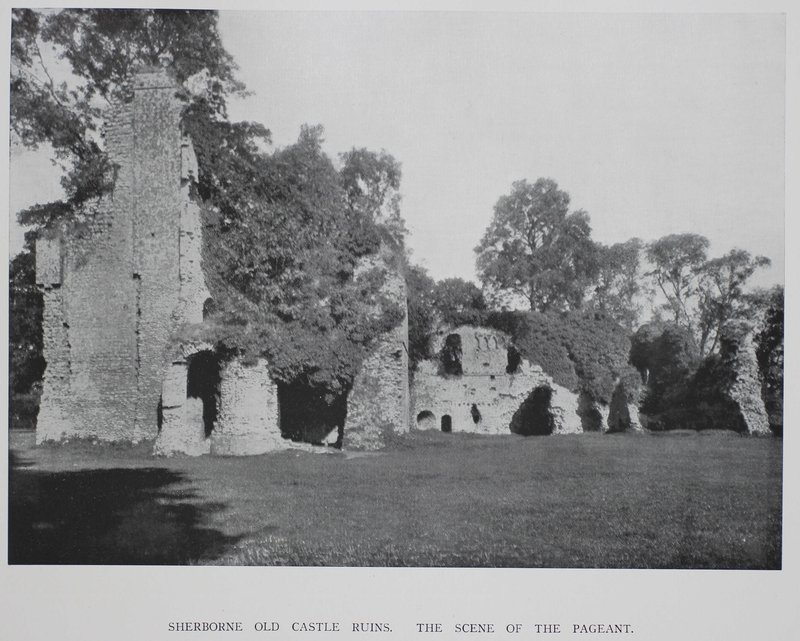

In 1904 Sherborne was a small sleepy town of about six thousand people, ‘a dull enough place to live in’, according to the Daily Express, bypassed by tourists heading for the coast of Cornwall and Devon. If it was unremarkable to onlookers, it nevertheless had a long and distinguished history. At one point the capital of the Kingdom of Wessex, King Alfred’s brothers Ethelbert and Ethelbald were buried in the towns Abbey, and it was home to a glorious sixteenth century Tudor mansion built by Sir Walter Raleigh, not to mention the even older romantic ruins of a twelfth century castle. Apparently unknown to many of its modern inhabitants its history went back further still, being founded by the bishop St. Aldhelm in 705 when the great Diocese of Winchester was divided into two. When Canon Mayo of the nearby Longburton village informed the Church Council in 1904 that the 1200th anniversary of this momentous occasion was approaching, it was decided that it would be fitting to have a local ecclesiastical celebration. Twelve months later most of Britain knew the name of Sherborne, and many towns and cities were scrambling to stage their own historical play as ‘pageant fever’ swept the land.

Source: Cecil P. Goodden, The Story of the Sherborne Pageant (Sherborne, 1906). Dorset History Centre: 791.624

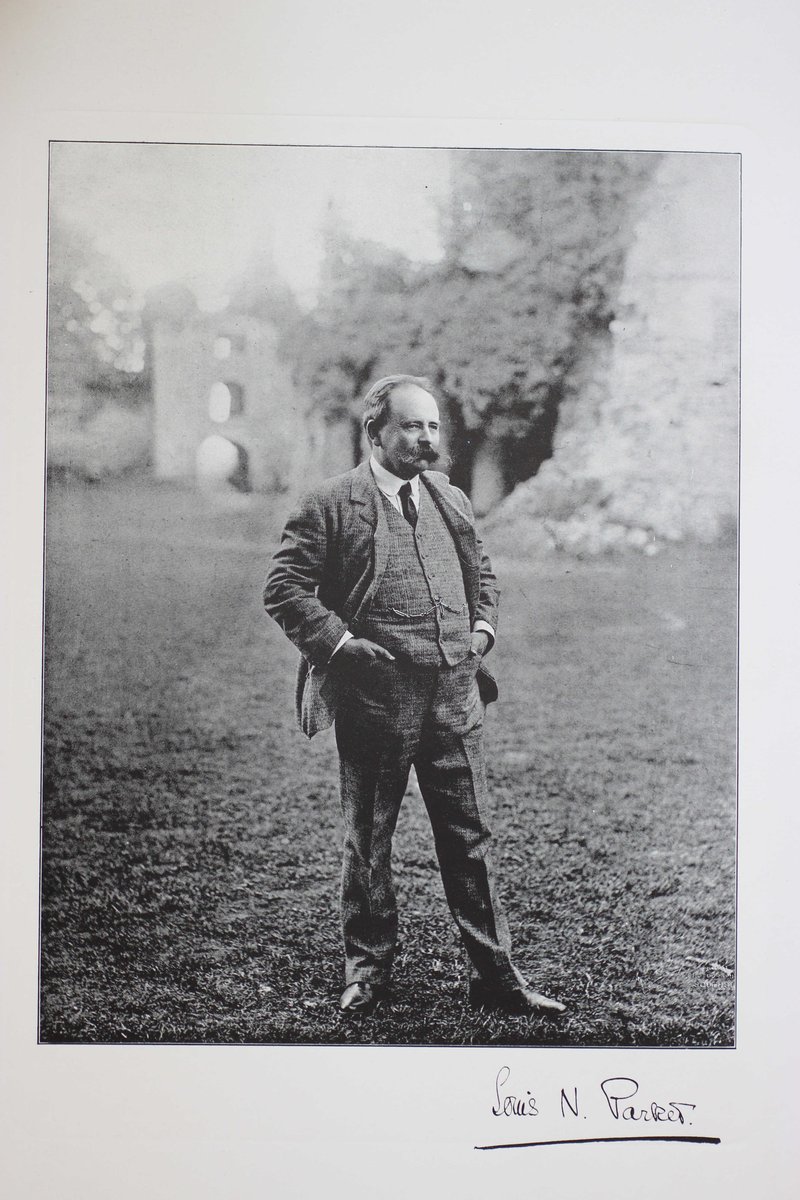

If Canon Mayo deserves the credit for bringing the anniversary to the attention of the Church, it was the Rev. Arthur Field who set in motion the chain of events that led to the staging of a grand local pageant. A former pupil of Sherborne School, Field recalled the local patriotic school songs written by his old schoolmaster Louis Napoleon Parker in the 1880s. Now a successful playwright and composer resident in London, Parker, a French-born English/American, jumped at Field’s suggestion of a play telling the towns local history as part of the anniversary celebration. Following a public meeting hosted by the town council in July 1904, at which Parker both charmed and brought the audience to a near-hysterical enthusiasm, it was settled. Drawing his inspiration from both English traditions of Shakespeare and mystery plays, Parker was also a devotee of Wagner and familiar with foreign customs like Schiller’s William Tell in Altdorf and the passion play of Oberammergau. Originally envisaged as a smaller event including ‘only’ three hundred performers, the cast of his modern historical pageant eventually grew to nine hundred. Crowds flocked from across the country, and even the Atlantic, to witness the innovative spectacle they’d seen glorified in both local and national newspapers.

Source: Cecil P. Goodden, The Story of the Sherborne Pageant (Sherborne, 1906). Dorset History Centre: 791.624

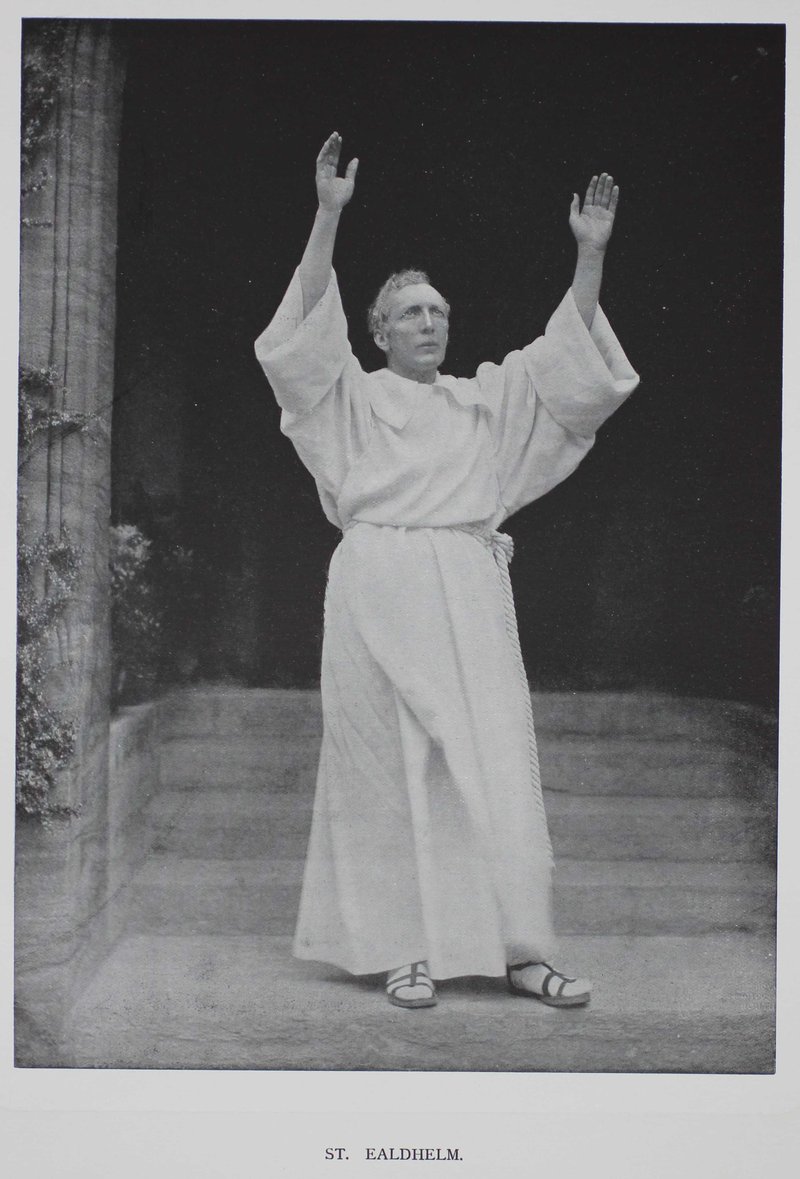

The pageant took place in the ruins of the twelfth century castle and consisted of eleven distinctive episodes, beginning with the coming of Ealdhelm in 705 and ending with a humorous, even farcical, visit from Sir Walter Raleigh in 1593. In between the whole story of Sherborne was told, from intense battles with Danish marauders in 845 and the imposition of the Benedictine Order on greedy drunken monks in 998, to the foundation of the twelfth century castle and the receiving of the schools charter in 1550. Religious themes and lessons loomed large, unsurprising due to the pageants origins, as did the notion of a Merry Old England, complete with maypoles and Morris dancing. Local history was joined to the history of England with the arrival of Kings and noble figures, as the pageant made a case for remembering Sherborne’s role in the larger life of the nation. Many of these themes were replicated across Britain in future pageants, as other towns rediscovered their history and the power it could have in the present-day. Indeed this was the point of Parker’s pageant; celebrating and performing local history could secure social stability and pride in both town and country. As he told a meeting of the Society of Arts in December 1905, ‘out of local patriotism, I think, springs a far finer national patriotism than any founded merely on rifle-clubs and Morris tubes.’

Bishop Ealhstan Defeats the Danes, 845 (Episode II). Source: Dorset History Centre – D.2259/6

All of the participants seemingly sank themselves anonymously into the organising and performing of the play, with Parker instructing the press to not print the names of any performers – though many could not help but notice the appearance of the famous actress Mabel Terry Lewis as Elizabeth Throckmorton in the eleventh episode. All the stage sets and costumes, apart from the armour, were made locally, and the whole town was bedecked in bunting and flowers celebrating 1200 years of civic pride. For the press and for Parker this was a display of classless cooperation, from ‘peasant’ to shopkeeper to squire, united in doing their best to put Sherborne on the map. In ending the narrative of the pageant hundreds of years before the present day, Parker avoided having to tackle any of the thorny social and political issues of the day. For him this made sense anyway; it was in Old England, untouched by ‘the modernising spirit, which destroys all loveliness’ that the true romance and poetry of the town could be found. Looking back provided lessons for the modern inhabitants; as the final ‘triumph song’ carolled of the great ship of Sherborne, ‘With twelve hundred years beneath her, and the bend of heaven above, Down the ocean of the ages lo! We launch her forth once more.’

The Death of Ethelbald and the Coming of Alfred, 860 (Episode III). Source: Dorset History Centre - D.2259/6

Over several days thirty thousand people packed themselves into the pageant grounds, two thousand each performance in the specially built grandstand and many more on benches or standing. Newspapers widely reported the overflowing attendances, suggesting that some visitors had paid two or three times the asking price for tickets to guarantee a seat. The Times praised ‘the beauty of the spectacle, the smoothness of the working, and the vividness of the effects’. The Speaker declared the pageant ‘a thing of such beauty’ that would ‘remain a joy in the memory of all who saw it.’ The Western Gazette, a champion of Dorset pageantry throughout the first half of the century, described the event as a ‘Gorgeous and unparalleled spectacle.’ Thrilled spectators wrote to the local press and the pageant secretaries to express their pleasure – a Mr Edwin Arrowsmwith, for example, saw the pageant three times, adding ‘I have witnessed many striking spectacles, including the last Delhi Dulbar, but nothing has ever pleased me more than the beautiful scene I witnessed with much grateful appreciation for all your splendid labours.’

Crowds pack themselves into the pageant grounds. Source: Dorset History Centre - D.2259/6

The crowds – ‘Beware of pickpockets’! Source: Dorset History Centre - D.2259/6

Unsurprisingly popular with American visitors and newspapers like the New York Times was the final tableau following the eleventh episode. Raised on a pedestal was a majestic female figure symbolic of Sherborne, holding a model of the abbey in one hand and a shield emblazoned with the school arms on the other. Alongside her was a younger woman, representing the American town of Sherborn, holding a model of a caravel, a type of sailing ship, and resting her left hand on the arms of the State of Massachusetts. This scene was the outcome of an exchange of letters and goodwill between Sherborne, Dorset, and Sherborn, Massachusetts, in the months leading up to the pageant. First contact had been made by the town clerk of the American town, Francis Bardwell, when he requested from the Church any possible information about Sherborne, Dorset - what he considered as the ‘Mother Town’ due to it being the original home of English emigrants who created Sherborn in the seventeenth century. Arthur Field replied with answers to Bardwell’s questions, as well as informing him of the upcoming anniversary and pageant. This elicited great excitement in Sherborn, who sent official greetings to the Mother Town, as well as announcing the pageant to the press in America. At the end of the pageant a Herald stepped forward and read the official message of greeting as the strains of the Star Spangled Banner burst forth from the Orchestra. Parker’s daughter played Sherborn, since she was an American descendant through Parker’s American father; by a strange turn of fate it even turned out that it was actually a descendant of Parker who had originally sold the land to the Dorsetshire emigrants.

The final tableau. Source: Dorset History Centre - Cecil P. Goodden, The Story of the Sherborne Pageant (Sherborne, 1906). Dorset History Centre: 791.624

The spectators were just as appreciative to Parker as the press, calling him back into the arena following the final performance to deafening applause. Sherborne school boys tore the rosettes from their caps, throwing them onto Parker has he went past; he was carried around the arena in a chair; and he shook hands with the performers as the band played ‘for he’s a jolly good fellow.’ When the time came for Parker to leave for London by train a tremendous crowd gathered to see him off, presenting a bouquet of flowers as there was more singing of ‘he’s a jolly good fellow’, accompanied by handkerchief and flag waving. Following the pageant the residents of Sherborne were intent on further showing their gratitude, inviting him back for a public presentation of two massive richly bound albums consisting of photos of the pageant and the autographs of all the performers. Parker, for his part, thanked the performers of Sherborne in the Dorset and Somerset Standard, stating that he could not ‘even begin to describe the enthusiasm and zeal with which they have carried out every small hint or wish of mine. When one realises that here were eight hundred people, not six of whom had trodden the boards, even as amateurs, the result is little short of marvellous.’

Source: Cecil P. Goodden, The Story of the Sherborne Pageant (Sherborne, 1906). Dorset History Centre: 791.624

Memories of the pageant continued far beyond 1905. The Story of the Sherborne Pageant, published in 1906, would, Parker argued, ‘help us to remember what it was… I see many an old man and many an old woman, too, for that matter, years and years hence, opening its battered covers and calling the children, and crooning: ‘This is what we did in the year 1905 to show honour to our dear town and to the dear school which is the glory of the town.’’ In 1925 a memorial block of granite, with an inscription commemorating the pageant, was unveiled in Sherborne by Parker, his speech maintaining that ‘the memorial would be a reminder to coming generations of how a handful of enthusiasts helped to restore to the country the ancient title of “Merry England” and showed some of its buried treasures of history, song, and romance.’ This twentieth anniversary was also an occasion for the Rev. Arthur Field, one of the original secretaries, to give a lecture on ‘Thoughts on the Sherborne Pageant’ to the members of the Congregational Brotherhood, where he put across his opinion that the ‘delightful spirit of harmony… lingered amongst them still.’ In this same year James Rhoades, one of the original writers of the pageant, published ‘In remembrance of the Sherborne pageant’ as part of a volume of collected poems. When Parker died in 1946 the event was again evoked, with the former Bishop of Salisbury, Dr. Neville Lovett, unveiling a brass to the memory of the pageant master in the Sherborne School Chapel, followed by a screening of the old pageant film in the Carlton Theatre to a full house. The pageant gardens, costing £700 and opened in 1906, were paid for and maintained using the £1872 profits of the pageant, and provided a lasting memorial to the event.

The Book of Words. Source: Dorset History Centre – PE/SH: PA2/5

The Sherborne pageant clearly deserves its status as the first modern historical pageant. While it was influenced by previous forms of ritual and local theatre, drawing on Parker’s knowledge of continental traditions especially, it created a distinctive format that was replicated throughout Britain and, indeed, North America. While certain aspects of pageant narratives became increasingly open to interpretation, such as the chronological spread of the episodes and the mixture of real and mythical history, certain aspects were dominant: pageants were voluntary, with the vast majority of performers being unpaid; episodes depicted historical events in a linear fashion; episodes also connected the history of the local with that of the nation; pageants were seen as a way to bracket class tension and create a sense of local community; and, while they were in a sense conservative in the way they looked back, they also projected values into the future – and were not above using modern methods of advertising and production. The Sherborne Pageant was by no means the biggest, but it was definitely a trailblazer, effecting a massive change in how Britons engaged with the past in the present of the twentieth century.

Disclaimer: My thanks to the Dorset History Centre for the permission to reproduce these images. For The Story of the Sherborne Pageant if you own the copyright for this book and wish to be credited, please contact historicalpageants@kcl.ac.uk.