Edmund of Anglia, 1970

The successful Bury St Edmunds Magna Carta Pageant in 1959 re-awoke an enthusiasm for historical re-enactment in the Suffolk town that had lain dormant since 1907. Around 50,000 people saw the performance, and it made about £33,000 profit in today’s money. Just eleven years later, the town decided to stage another. Dubbed ‘Edmund of Anglia’, it was really more of a pageant-play. The site was again the Abbey Gardens, where the pageant was staged 19 times in the summertime. It was the main attraction of the Year of Edmund - a series of events, including choral music, orchestral music, a carnival, and church services, that commemorated the 1100th anniversary of his gruesome martyrdom. Based on a series of events in the short life of one figure, 'Edmund of Anglia' wasn’t a historical pageant in the same vein as the 1907 and 1959 spectaculars. But it still drew upon the strong pageantry tradition in the town and shared much with the first two events. But, unlike the productions mastered by Louis Napoleon Parker and then Christopher Ede, it faced a surprising amount of vocal public criticism, and even an organized protest! Bury St Edmunds had been undergoing many social and economic changes since the end of the Second World War. By the time the town had geared up to produce a pageant again, these changes reached maturity, and made the pageant seem, at least to some, strangely out-of-touch. Nonetheless, it played to an almost full capacity and, even though it made a small loss, it was deemed by most to have been a success; another example of the pageantry spirit in Bury St Edmunds - though, as yet, also the last.

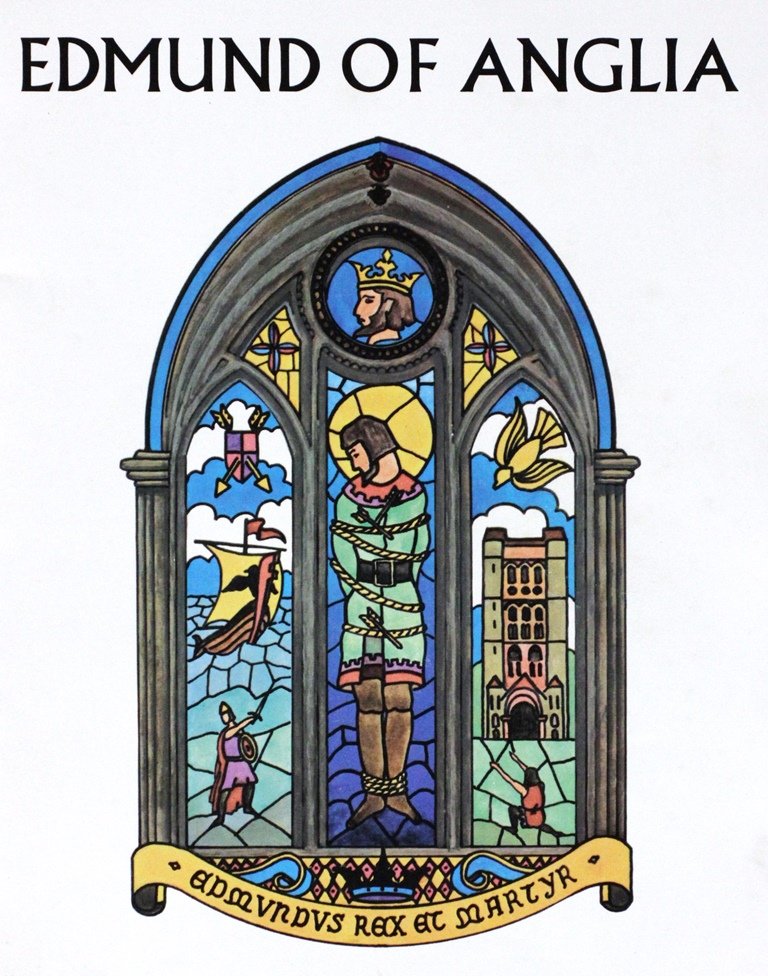

Cover of the pageant programme. By kind permission of the St Edmundsbury

Heritage Service.

First suggested by Councillor Harry Marsh, the Year of Edmund was primarily organised by the Borough Council in cooperation with local associations, clubs and other bodies. The pageant was publicly launched with a promise of £6000 (£60000 in today's money) of funding from the Council, and £4000 (£40,000) from a variety of local businesses as well as the branches of national businesses, such as Adnams, Barclays, Lloyds, Sainsbury’s. It was written and directed by Olga Ironside Wood, the County Drama Adviser for West Suffolk and the designer of some of the costumes for the 1959 pageant. She also wrote plays, and had previously produced a Civil War pageant at Stoke Poges in Buckinghamshire. Wood confidently declared in the programme that the story had ‘almost wrote itself’, and had ‘everything… war, peace, violence, suspense, betrayal, tragedy, idealism, strong human interest and glitter and spectacle.’ She also tried to relate ‘this wonderful story of one man’s fight for his beliefs against overwhelming odds’ to ‘life today’. A historical procession of figures such as Stephen Langton, Tom Paine, Abraham Lincoln, ‘Negro Slaves’, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Jan Palach suggested a link between the story of Edmund and other martyrs and struggles for freedom.

But, in the main, Wood's story focused on a serious portrayal of Edmund’s life. It began at the Palace of King Offa, as he picked his cousin’s son, Edmund, as heir to the throne. In later scenes the dying king crowned Edmund, who then went to meet the people of Beodricsworth. The peace-loving Edmund had a quiet time, until King Lothparck of the Danes washed ashore. When Lothparck was killed in a fit of jealousy by Edmund’s huntsman, Berne, it set the scene for a Danish invasion. When Edmund was captured, and refused to renounce his Christian faith, he was shot through with arrows. While there were some moments of humour, not least a pair of Scandinavian wrestlers, there was certainly no happy ending!

King Offa and his courtiers land in their boat. By kind permission of the St Edmundsbury

Heritage Service.

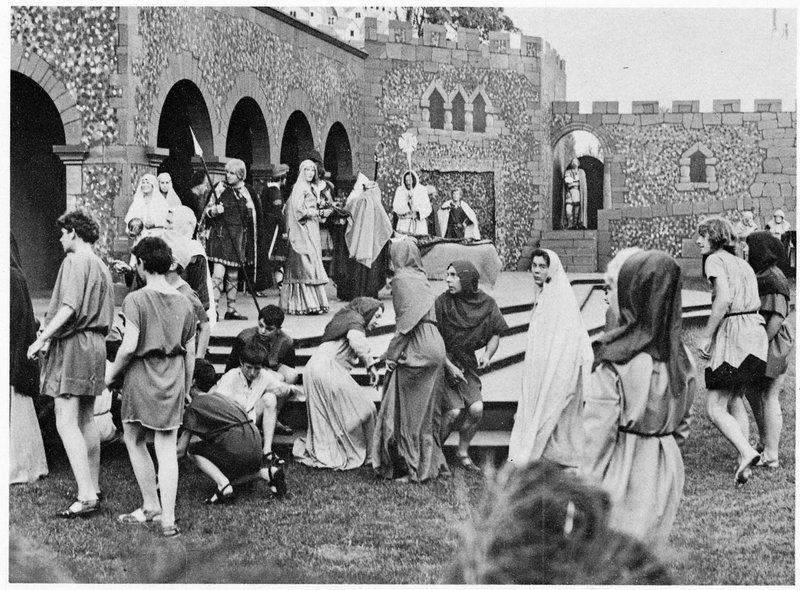

The crowd at offa's palace wait for Prince Edmund. By kind

permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

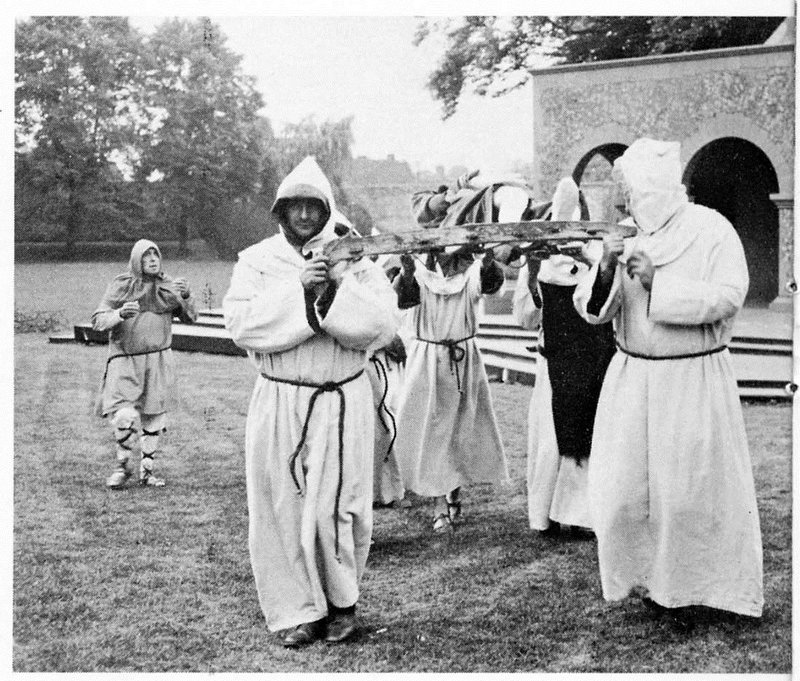

Monks recover Edmund's body after his martyrdom. By kind permission

of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

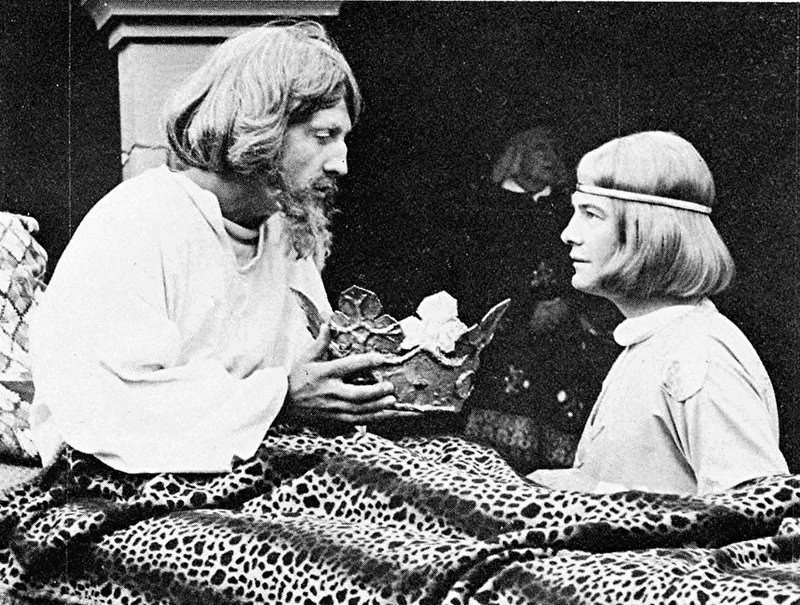

Edmund is crowned by King Offa on his deathbed - by kind permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

Compared to 1907 and 1959, the cast was much smaller, with only 312 taking roles - many of which were doubled parts. A great deal of the work was done voluntarily. Local schoolboys made the shields, weapons, and many of the other properties, and, for almost a year, a team of ladies met weekly to cut out and sew hundreds of costumes. The only people paid for their part in the production were technical administrators and sound and light technicians. This ethos of voluntarism and participation was still a fresh memory of the town’s last pageant, encouraged through photos and stories about its staging in the special 'Festival of St. Edmund' supplement (produced by the Bury Free Press). Some performers and participants from the previous pageants also got involved again. Harrison Oxley, who wrote and conducted the music for the 1959 event, again took that role in 1970. There was even one performer, Harvey Frost as the Royal Physician, who had performed in the 1907 pageant!

Part of the advertising buzz coming from the organisers was about marketing the Edmund Year to the younger people of the town and county. Under the heading of ‘youth, liberty, participation’, in a programme distributed to local organisations, the celebrations co-ordinator, councillor John Knight, pointed towards the martyrdom of the ‘young King’ and declared:

"In 1970 let us reflect on the fast expanding knowledge, experience and comprehension of our fine generation of youth – and the power and responsibility that go with it. Where better to call for vigilance for liberty in Britain and the world beyond than Bury St. Edmunds, whose links with Edmund and Magna Carta shine in the motto ‘Shrine of the King, Cradle of the Law’?"

Knight later expanded on this ideal, telling the Bury Free Press that ‘A feeling for history and tradition, for freedom, for people – particularly youth – and for the arts and other leisure time activities’ had led him to accept his duty to commemorate the King’s martyrdom. Just like 1907 and 1959, the Mayor also stressed the connections between portraying the past, and preparing for the future. In the pageant programme he envisioned how ‘Our pride in our past stimulates those of the present to foster the pride of today and to work and plan for our future, so that Bury St. Edmunds will continue to be a centre in which it is a pleasure to work and live.' He claimed that the Council was 'deeply conscious of this when planning for the future, so that the “Old and New” will blend in perfect harmony.’

But, from the beginning, there was anything but ‘perfect harmony’. Opposition to the Edmund Year, and the pageant in particular (reacted to just as vigorously with counter-opposition from diehard supporters), turned the letters page of the Bury Free Press and East Anglian Daily Times into a battleground. At one level, the celebrations were criticised by one local for using Edmund as a cynical ploy to ‘boost the trade and tourist value of the town… allowing commercialism to obliterate the Christian values by which St. Edmund lived and for which he died.’ In the same issue, a defender of Edmund stepped forward, and opined

"Is it not about time the chairborne critics of the Edmund celebrations devoted more of their misplaced energy to thinking up feasible alternatives to the Festival rather than criticising with monotonous regularity, the honest efforts of others through your correspondence columns?... Those whose favourite pastime seems to be sitting on an over-ample posterior writing anonymous criticism to local newspapers tend to remain traditionally critical of local events regardless of their subject or content, but we have yet to hear one practical suggestions as to how they would deal with the problem of pleasing all the people all the time."

Harry Marsh, chairman of the Bury Town Council Publicity Committee and originator of the celebrations, replied to the distressed Catholic, informing them that ‘claiming that commemoration is being used for commercialism appears to be from one who has not attended the solemnising events or has been unable to enter into the spirit and meaning of the Festival.’ As he pointed out, there had, after all, also been other associated services in Anglican, Catholic and Noncomformist churches – actions that were ‘utterly sincere’ in their ‘dedication and thankfulness’.

But the debate between about commercialisation and religion was only one side of the coin. On the other, there was a lot of criticism that the celebrations were even utterly irrelevant. One local man expressed his sadness that the council seemed so interested in trying to promote Edmund as the patron saint over George, what he thought was an ‘insignificant issue’. There was, he argued, a danger that problems currently being faced would become obscured if too much attention was placed on past events and ‘obsessions’. One such problem, he pointed out, was the Jacqueline Close affair – ‘a disgrace to the reputation and social conscience of the town’. He was referring to an on-going dispute the residents of Jacqueline Close were having with the town council. In 1967 it became clear that the remnants of old mine workings underneath the houses were beginning to suffer from subsidence. After a major collapse in 1968, when a large amount of one house was swallowed by a hole, the area was declared unsafe by the local council, who suggested the residents should leave. Those who stayed behind decided to organise themselves, and sought compensation or repair, which the council deemed too expensive. Before the Borough Council went about creating another historical pageant, which the man argued was merely the ‘preservation of prestige concepts and projects’, the poor folk of Jacqueline Close should first be helped. During an immensely popular carnival procession for the Year of Edmund, around 12,000 people lined the streets of the town to watch the 100 entries (including 52 decorated floats). In amongst the celebratory floats, the press could not help but notice a plain undecorated Land Rover with a protest slogan, “Bury Jacqueline Close?”, on its side.

Others were more concerned with economic matters, and believed that pageantry and history would do nothing to further the progress of the town. One letter, signed mysteriously as ‘Newcomer’, told the Bury Free Press that

"The sooner Bury councillors free themselves from their pitiful pre-occupation with the dim and distant past and devote the time to dealing actively with the problems and needs of a living community the better it will be for the town. To become an efficiently and economically-run town keeping abreast of modern standards will do far more for the name of Bury St Edmunds than arranging carnivals, plays, processions, and bun fights in an attempt to revive the past. To those people who seem obsessed with Bury’s glorious (?) past, may I suggest the necessity of trying to ensure that Bury has a future a little more glorious than is indicated at the moment."

In stark comparison to the enthusiasm of 1907 and 1959 there was even open dissent in the town council. When Harry Marsh's proposal to commemorate the 1,100th anniversary of the martyrdom was recommended by the publicity committees to the council, some councillors replied that "The past was over and over with"! Alderman J.M. Painter was particularly blunt, telling one council meeting that it had ‘something better to do, having many more problems than to become concerned over a dead king’. If a councillor had expressed this opinion in 1907 or 1959, they may have been kicked into a different county. But, in 1970, several other councillors even backed up Painter.

The criticism of the St Edmund Year reached its most vitriolic after the pageant actually began its lengthy run. Particularly emphatic was a letter to the Press from another mysterious contributor: Achilles Heel. In an amusing but angry rant, he exasperatingly voiced how

"This town has never ceased to surprise me with the capacity to exhibit every sign of fossilization, and yet continue to exist. In your edition of July 3 the usual wealth of local news gems were augmented by an orgasm of worship praising the St. Edmunds Pageant farce. In your supplement you ask the question, “Who was St. Edmund?” to which a not inconsiderable proportion of those freedom loving young people of Bury will reply “who cares?” With the exception of a group of the frightfully ‘county set’, the towns businessmen and some egocentric senile delinquents, a large proportion of Bury’s population do not know and do not care about St. Edmund, or the pathetically embarrassing series of events intended to colour his 1100th anniversary… The people on the estates around the old heart of the town are not involved in many of the so-called commemorative events, and see the whole affair as a waste of ratepayer’s money on what is proving to be an advertisement for the businesses of the town… Rather than despair of any change occurring that might alter Bury and cause a radical shift in its conservative outlook I continue to live in hope that this year’s Pageant will serve to convince Burians of the monumental waste of their money."

The Achilles Heel letter, not surprisingly, rubbed many up the wrong way. One wrote back and declared Achilles Heel ‘despicable’, arguing that ‘Doubtless certain local bovver boys care little for Edmund, so in their ignorance they fail to appreciate our tolerance of them – brought about by a feeling of compassion towards all mankind in general, and drop-outs in particular’. These traits, he pointed out, had been ‘handed down’ from the saintly Edmund. Achilles Heel, revealed to researcher Tom Hulme in 2014 as Julian Putkowski (then a local 23-year-old), then went even further, by organising an alternative satirical pageant of his own, along with several similarly minded friends. Named ‘Ed the Toadstool’ it took the form of a puppet show in the Abbey Gardens, and was seen by a ‘fair-sized crowd of interested and amused onlookers’. When a park attendant tried to intervene one of the crowd shouted ‘Shut up, we’re enjoying this’ – proving that not everybody disagreed with Achille’s antics. Inevitably the puppet-pageant also attracted the attention of the police who, to their credit, let the twenty-minute performance finish before informing the puppeteers that they actually needed a license to perform in the gardens. The Bury Free Press responded in a surprisingly tolerant manner, writing that ‘one has to admire their spirit and impish sense of humour, to say nothing of the orderly way they conducted themselves at all times, despite being somewhat thwarted in ambition.’ After all, as they said, ‘when reaction is confined to good-humoured “taking the mickey” in order to make a viewpoint heard it’s a thin skin that cannot appreciate the joke of it all.’

Putkowski’s protest and backstory neatly encapsulated the ways in which Bury St Edmunds had changed in the previous twenty years. Son of a Polish furniture-restorer, he had grown up on the new Mildenhall housing estate. In 2014 he remembered how

"There was an alternative Bury St Edmunds, populated by young late-teens and early twenty year olds during the mid to late 1960's for whom the pageant was a costly irrelevance. They weren't really party political but took umbrage at the large amount of money that was being squandered on the pageant. My principal complaint was that it was a business promotion and had damned all to do with the majority of the townsfolk and as I think I indelicately expressed it f##k all to do with folk living on Mildenhall and Howard estates. Then, and I surmise to some extent nowadays the overwhelmingly working class estate dwellers were marginalised."

Since the end of the Second World War, the town had seen a massive period of expansion. By 1960 the construction of the Mildenhall Estate was well under way, joining the Howard estate and housing on Nowton Road. Industrial estates also sprung up, as Bury St. Edmunds actively courted London firms under a town expansion scheme. Agriculture, though still important, was joined in the local economy by new businesses of many kinds – from Nilfisk, the Danish vacuum cleaner manufacturers, to Vitality Bulbs and Vintens, who made specialised cameras. The population of the town correspondingly grew. After staying at around 16,000 people from 1881 to 1931, it reached 20,056 in 1951 and 25,661 in 1971. These economic and social changes, and the blurred suburbanised development they encouraged, were not welcomed wholeheartedly. As the famous historian of Suffolk, Norman Sharpe, lamented: ‘the extraordinary decision to double the town, from 20,000 to 40,000 is relentlessly changing both its heart and country setting.’ While there was an inkling of these changes in 1959, by 1970 they had become properly visible. The problem, for Putkowski and others, was that the civic elite had not kept in-step with the changing town demography. As he further explained,

"It is perhaps difficult [in the 21st century] to appreciate the extent to which Bury St Edmunds during the 1960's was Torytown, very much influenced by the farmers and landowning squirearchy but controlled directly by an oligarchy of powerful individuals associated with the the Con(servative) Club and local Freemasons - specifically the Magna Carta Lodge. If you check the Mayors of Bury St Edmunds during the 1960's and possibly earlier, I have a hunch that they were all on the square - with possibly one exception (a local Co-op manager). It wasn't an occultish, malevolent mafia but more a small town confluence of interested parties."

Putkowski could, of course, be exaggerating, but it does seem that he was right about something: to the newer residents of the town, the pageantry format may have been bright and colourful, but it seemed strangely quaint and obsolete.

A scene from the pageant - by kind permission of Margaret

Charlesworth

A scene in the pageant - by kind permission of Margaret Charlesworth.

Still, we should not get carried away in condemning poor old ‘Edmund of Anglia’. If there had been an intriguing protest, the press was also, as usual, mostly complimentary about the amateur performers effort- an ‘absorbing spectacle’ that was both ‘colourful and entertaining’. John Knight also told the press that there had been a ‘wonderful spirit of co-operation and enthusiasm which has manifested itself in so many ways in diverse places’ – another sign that all that was so important in 1959 had survived. In attendance terms the pageant was not seen by anywhere near as many people as in 1907 or 1959 but, by its own measure, it was still a success. Of the total 14820 seats available to see the play, 14,050 were occupied, and the only vacant seats were in the first few days. Not a patch on the huge crowds of 1907 and 1959, but pretty respectable. More concerning was the small loss, costing a ¼d rate in the borough - though Knight commented that it was still ‘exceptional value’, the benefits of which would be ‘felt for some years to come’. Despite the disagreement on whether ‘Edmund of Anglia’ was a success or not, it was the last major pageant in Bury St Edmunds. In 2015, as we celebrate both the anniversary of Magna Carta and memories of historical re-enactment throughout the twentieth century, perhaps a new set of pageant-masters and pageanteers will be encouraged to take up the mantle, and restore Bury St Edmunds to its proud place as a natural home of pageantry.