The Pageant of Ayrshire 1934

This pageant of the month may have taken place 80 years ago, but it engages with something of a present-day topic of interest given that Scotland may vote to leave the Union on 18th September 2014.

The Pageant of Ayrshire was subtitled, 'The Story of Scotland's Struggle for Independence', however if the organisers of this large-scale event did have any particular political messages to deliver, contrary to what this title might imply, they were certainly not aimed at severing ties with the UK. Instead, this pageant loudly celebrated all that seemed vital in the 1930s for the maintenance of Scotland's position as an equal partner within the United Kingdom. Indeed, this was a pageant untroubled by political nationalism but very much concerned about the preservation of Scottish cultural identity within the Union.

Its overall message was to highlight the place of history in the formation and safeguarding of Scottish national identity, in spite of the Union of 1707, and to evangelise about the importance of the county of Ayrshire in the bigger picture of this national historical narrative. And indeed, there was plenty in the way of local legend in order to successfully do so.

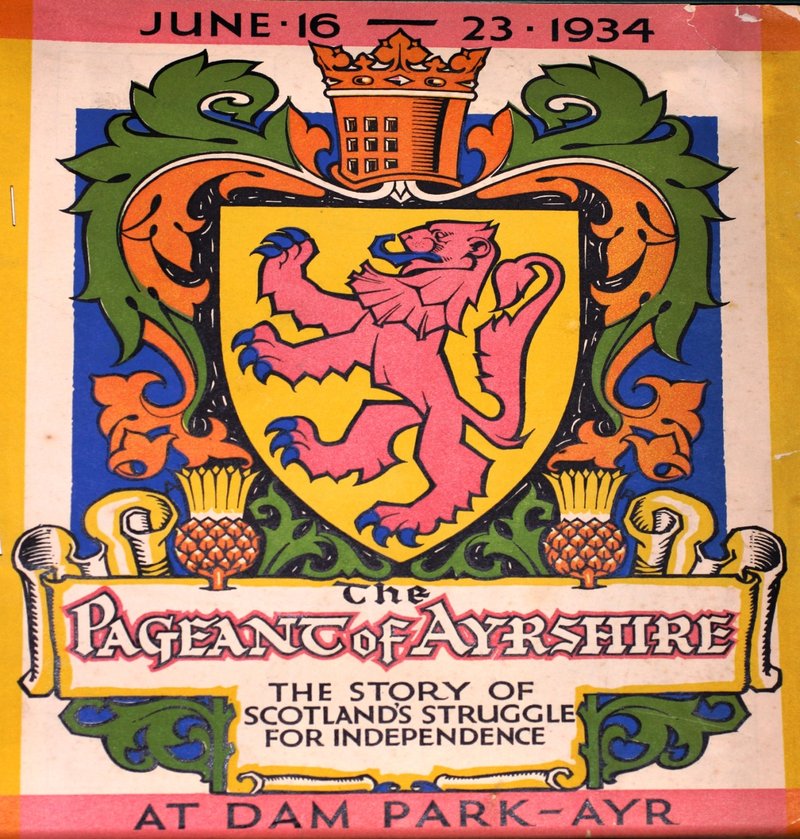

Cover of the souvenir programme for the Pageant of Ayrshire

The Pageant of Ayrshire was held in the ancient burgh of Ayr and was the largest event of this type to be held in a Scottish town up until this date. Following its eight performances held between the 16th and 23rd June 1934, it was reported that the pageant had attracted an audience of almost 92,000. For a wee seaside and market town this was a massive achievement, but small or no, Ayr took its position as the cultural seat of its namesake county very seriously. Consequently, in its role as host for this pageant, it had never aimed small.

Over 3000 people from across Ayrshire performed in the pageant, which had six episodes: beginning with prehistory in Episode 1, which depicted the legend of King Coilus, and ending with an extravagant celebration of the life and works of the poet Robert Burns in episode 6. Throughout, individual localities or organisations took charge of particular scenes within each episode, or for some, the entire episode was in their charge. So for example, Ardrossan, a coastal town in the north of the county, organised all of episode 2, which recalled a great battle between the Scots and the Vikings in 1263, following which Alexander III of Scotland put an end to Viking influence in his realm. And the industrial town of Kilmarnock situated in the east of Ayrshire, was entrusted with episode 5 on the Covenanters. Given that perhaps the most famous Scottish covenanting martyr, John Brown, hailed from nearby, this organisation of the pageant paid proper heed to local ownership of the past.

Naturally, the town of Ayr's big contribution was episode 6 on the life and work of their most famous literary son, and renowned champion of liberty, Robert Burns, who more than any other figure from the past had made Ayr into a place of international pilgrimage.

Performers in the Robert Burns episode depicting the Jolly Beggars at Poosie Nancie's Tavern

The Burns episode, which included four separate scenes, was hailed at the time as spectacular and moving in equal measure. One scene included a ballet performed by 250 witches in an enactment of the famous verse Tam O'Shanter; but as well as capitalising on the humour and drama of Burns' poetry, the personal travails of the poet at the end of his life, were also poignantly depicted.

'...the history of Ayrshire is, in a large measure, the history of Scotland.'

Although this pageant celebrated local history, all of the publicity surrounding it also proclaimed loudly that the performance would tell the national story. In early publicity and continuously up until the event, the pageant was described as 'not an Ayrshire, but a Scottish pageant'. While this type of aggrandisement was hardly unusual within pageants, it worked particularly well in the context of Ayrshire. The county was the birthplace of national heroes such as Robert the Bruce (celebrated in episode 4) as well as Burns. Moreover, the Ayrshire landscape was littered with monuments and landmarks recalling the arch liberator William Wallace who was depicted in episode 3 of the pageant. The use of Scotland's most iconic freedom fighters and the notion of 'struggle' worked successfully to encourage the widest possible audience, drawn not just from the local area but also from the large numbers of holidaymakers and day-trippers who arrived during the summer months to this part of the Clyde coast. The event was also aimed at international visitors who it was expected would flock to immerse themselves in the heritage of the ‘land of Burns’. And flock they did.

Local amateur artist, Roy McLean, created an illuminated manuscript as a record of the pageant. Here William Wallace is depicted in Monkton Chapel in Ayrshire pledging his allegiance to Scotland.

The Pageant Master, Matthew Anderson, was an energetic and imaginative publicist; under his leadership, pageant organisers enlisted the partnership of shipping companies to promote the pageant in North America and on the European continent. Capitalising on Scottish migrant networks and the international appeal of Scotland's national bard and his Ayrshire antecedents, news of the pageant was spread to Burns Clubs and similar Scottish émigré societies worldwide. The pageant was advertised at the Lyons Industrial Fair in March and at the Scottish Travel Exhibition held in London in April and May 1934 where tickets were sold by the player who took the role of 'Cutty Sark' in the Tam O'Shanter scene.

Publicity Still of Matthew Anderson in 1934

'The most elaborate open-air drama ever presented...'

Anderson came to Ayrshire fresh from his organisation of several large events in England. Originally a journalist who had found a niche in writing and directing pageants he was, despite his English pageant pedigree, also ‘a perfervid Scot and an Ayrshire man to boot’. His interest in the Ayrshire pageant was therefore both professional and personal. It was also commercial: the deal Anderson agreed with Ayr was for ‘ten per cent of the gross takings, less entertainment tax.’ With considerable flair he pursued the idea that the Ayrshire pageant should be the best ever show, and not just in parochial Scottish terms. Evidently, with the example of larger pageants held south of the border in mind, he further said that it would also be ‘the most striking pageant attempted in Great Britain… not through any particular merit of the scenario, but because of the subjects with which it dealt.’ Implying that the Scottish national drama could steal a march on anything England had to offer for excitement and romance, and, for the fervour of its patriotic message. In order to ensure that this ambition was achieved, Anderson also authored the script. He certainly had chutzpah!

Anderson's skill paid off: the Pageant of Ayrshire was a huge success. Impressive staging and generally good weather helped, as did the attractions that Ayr as a town had during the interwar years with its long esplanade and busy market town atmosphere. Yet more important than all of this, was that the pageant's underlying message seemed to hit the right note at the right moment, for as predicted, the story of Scotland's struggle for independence had considerable appeal, both for the participants and the audiences.

Illustration from the front cover of the Official Book of the Pageant of Ayrshire

Exploiting the zeitgeist.

The theme of this pageant suited the mood of the times. Unemployment, strife and political unrest were widespread in lowland Scotland in the early 1930s, and memories of WW1 were still potent, so that the message that Scots were made of sterner stuff was a resonant one. However, the retelling of Scotland's historic fight against English despotism and applause for the independent spirit of the Scots were not aimed at arousing dissent, indeed, quite the opposite was the case. Would such a nation of successful freedom fighters ever have allowed their country to be coerced into union with a larger nation? And having joined forces, would they ever have deserted their allies in war?

The fact that most Scots easily identified as 'British' and could do so without the loss of all that made Scottish identity unique was the cause for celebration in this pageant. The fact of political union was simply not the issue; this, for most Scots at this time, was taken entirely for granted.

Ayrshire International!

The finale of the pageant included not only all of the performers from previous episodes, but also a grand international procession with around 300 Ayrshire performers dressed in the national costumes of countries from across the globe. It presented a striking spectacle, and was all the more remarkable given that this splendid show was staged against a backdrop of severe economic depression. The nations were depicted paying homage to the literary genius of Burns, and of course, in doing so they were displaying their debt to no less than the land that had given Burns to the world: that land was Scotland.

Performers depicting 'India' in the Finale of the pageant

Organisers of the Pageant of Ayrshire clearly did not feel the need to undersell themselves! Two years later, in the summer of 1936, and still buoyed by the success of its county pageant, Ayr held another historical event. Entitled, The Romance of the Road, it celebrated the centenary of the death of the engineer John 'Tar' Macadam. All of the augurs were good for this pageant as well: brilliant weather, interesting props from the world of travel, local enthusiasm from the performers and so forth... but sadly, it flopped. At least one of the reasons for this failure was its lack of attachment to exclusively Scottish themes. The local press stated that this performance, despite its celebration of yet another local son who had achieved international fame, failed to privilege 'the Scottish scene'. So that for the audience, 'there was uncertainty as to whether the `occasions we were witnessing were in England or Scotland.'

Flying the flag for Scottish culture and national identity.

This cautionary experience underlines the fact that in the 1930s, while most Scots were perfectly happy to be British, and indeed, this particular pageant was, like all others, closed in traditional style with a rendition of God Save the King, for popular displays of history, Scots were not content to play second fiddle to their larger neighbour. Keeping the spirit of Scottish independence alive through enacting the past was too important to be sidelined within a narrative that might be viewed as generically 'British' or, dare it be said, too easily mistaken as English. In countless pageants held in Scotland, icons of Scottish independent thinking such as Wallace, the Bruce, the diehard Covenanters, and the poet Robert Burns were a means of keeping alive the meaning of Scottish independence within the Union and reinforcing the contribution that Scottish attributes had made to the strength of Great Britain. These events promoted the notion that Scottish identity would never be undermined so long as the history of Scotland's struggle remained in popular consciousness. Lurking in the background of such patriotic feasts was, of course, the spectre of the eventual disappearance of a separate Scottish identity, should the national tale ever be forgotten.

Changing Times?

That spectre did not emerge and in their time, events such as the Pageant of Ayrshire played a significant role in warding it off. Moreover, interest in Scottish history has continued to grow and continues to inform identity politics. Yet, approaches to the national story have inevitably changed and perhaps because of this the ending of the tale of Scotland's struggle for independence may be about to be re-written. The election that will take place in 2014 would have been unthinkable to the great majority of Scots in 1934 when the struggle for independence was widely viewed as having been settled, if not wholly amicably, then at least pragmatically, in 1707. Recent history suggests otherwise. The organisers of the Pageant of Ayrshire may well be turning in their graves! Or, perhaps, they may see this as the inevitable sequel to a story that has proved to be extraordinarily resistant to being subsumed and forgotten. For one relatively small band of stalwarts, this certainly was the case: 1934 was also the year when the Scottish National Party was formed.

*All images are shown with the kind permission of the local history section of the Carnegie Library in Ayr; I also wish to thank all of the staff there for their enthusiastic support with research for the project.*

Linda Fleming