The Aberystwyth and Cardiganshire Peace Pageant of 1935

After the First World War, the League of Arts for National and Civic Ceremonies was charged by a Parliamentary Committee to consider how peace should be celebrated in Britain. Theatrical performance loomed large in its suggestions, which were then taken up by the government - from the performance of open-air Shakespearean plays in all of the London boroughs, to the Thames Pageant, where 500 barges, decorated in honour of the mercantile marine, sailed down the river. Frank Benson, the famous Shakespearean actor and director as well as a pageant-master, was an important leader of the League. He insisted that for a country suffering from ‘the prevailing paralysis of artistic expression’, peace pageants would ‘resume, symbolise and express all that is noblest in our national history’ and act as ‘the greatest panacea’. The Aberystwyth and Cardiganshire Peace Pageant of 1935 was one such event. It took place in the ruins of the town’s 13th century castle, and was performed only once, to a full audience. The pageant contained elements of historical performance, but unlike most of our featured pageants, the characters and incidents were drawn from all over world, and used in the service of a message of peace, rather than local or national pride. Still, the Mayor, Alderman David Edwards, found an opportunity to use the pageant as a reflection upon the civic patriotism of town, expressing his pleasure, though not surprise, at Aberyswyth giving ‘such a splendid lead to the counties of Wales and England.’

The Castle Ruins today. Photo taken by Tom Hulme, 2014

Throughout the interwar period, peace pageants were organised regularly by the League of Nations Union, an organisation that hoped to internationalise citizenship, promote cooperation between nations, and prevent any future outbreak of war. Aberystwyth’s peace pageant was not organised directly by the League of Nations Union, but the local press reported that the ‘primary aim’ was to ‘state a case through pageantry for the existence of the League of Nations’. The Reverend Gwilym Davies, though not listed as an organiser or performer, was undoubtedly the key local figure in this respect. Thirteen years prior to the pageant he had retired from the ministry to devote himself to bringing about peace. He joined with Lord David Davies in creating the Welsh council of the League of Nations Union, headquartered at Aberystwyth, where he acted as its director until 1945. One of his first acts was to conceive of the peace message of the youth of Wales to the youth of the World, which took advantage of emerging wireless technology and was annually broadcast from 1922 – and is still going today. The Mayor, in his souvenir ‘Message’, mused that the pageants ‘dramatic rendering of incidents relating to peace and war’ would ‘promote intelligent thought and fruitful discussion of the pressing problems of our time. In reality, the narrative of the peace pageant sought to portray a much simpler story.

The pageant was split into three parts and began with ‘Towards Peace’, by far the longest episode. It started with an announcer declaring

‘Here, within the mouldering walls of a castle by a soldier king to dominate a people by military force… Here, beside a monument dedicated to the perpetual remembrance of men of our own generation who gave their lives in the belief that their sacrifice was the last of its kind to be demanded of men… Here, it is dramatically fitting that we should present our Pageant of Peace.’

The War Memorial. Photo taken by Tom Hulme, 2015

He went on to explain that

‘through the ages, men and women have challenged the war; insisting that there were better ways to secure justice between men and man, between nation and nation… To-day, we celebrate and review the efforts of those who have sought the better way, exhorting their fellows through example and precept to ‘seek peace and ensue it.’ ‘

The following incidents first served to explain the various motives of war, mostly mimed as the announcer explained the significance of each. The first incident showed a group of schoolboys playing a game, fighting, and reconciling – an example, the announcer said, of how, ‘when anger has cooled’, men are ‘ready to forgive and forget.’ Following incidents were historical. First up were Joshua and the military leaders of the Hebrews. After interrogating two spies they had sent to infiltrate Jericho, the details he obtains leads him to send his army against the city. As the announcer explained, ‘Desire to possess a country of their own led the Hebrews to make war upon the Canaanite peoples. Conquest has, through the ages, been a frequent motive of war.’ Next came a party of Arab raiders with booty, an example of ‘war motivated by the desire for plunder.’ A party of Aztec warriors, leading prisoners destined as sacrificial victims, symbolised the ‘demand for human victims’ as a cause of war. Arab slavers showed the desire of profit for war, while Louis XIV and Napoleon Bonaparte, ‘men of colossal egotism’, were examples of how vanity, jealousy, and greed ‘plunged nations and even continents into war’.

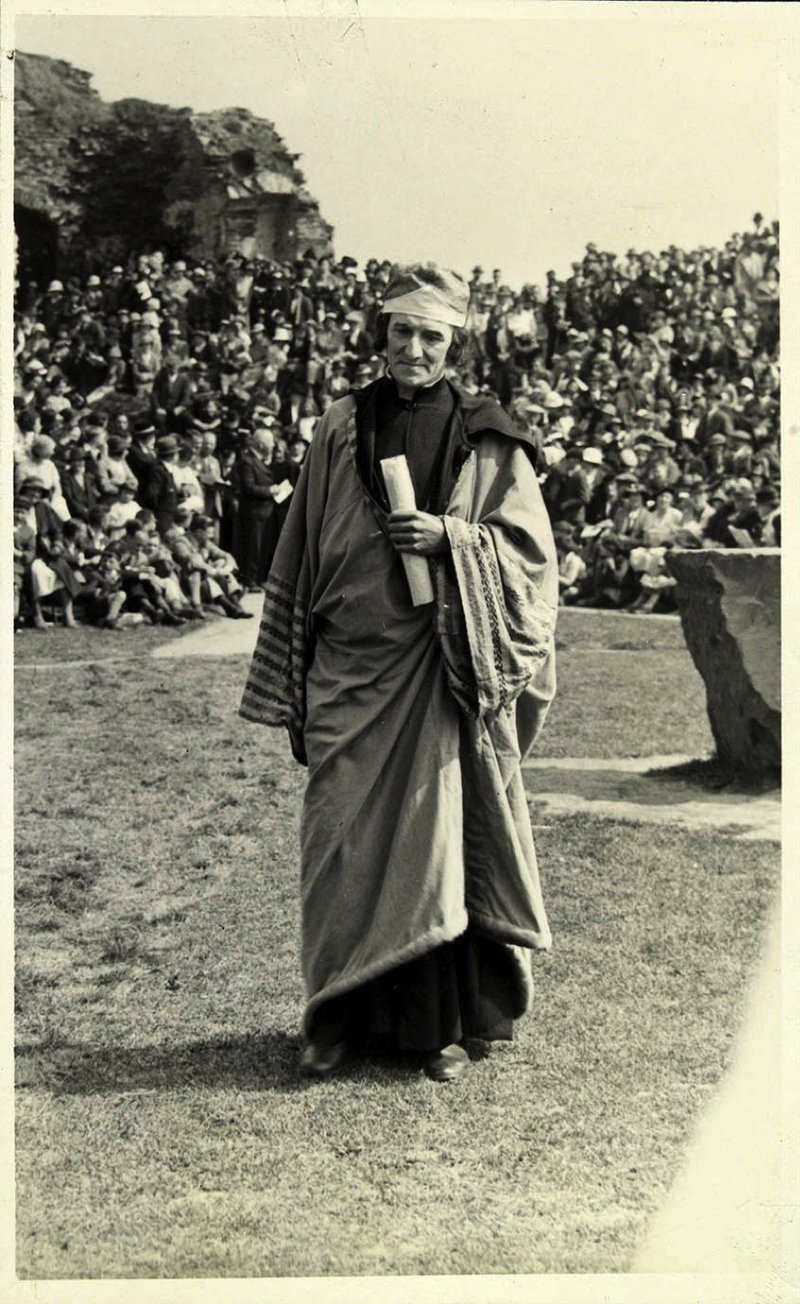

Napoleon Bonaparte. By permission of the National Library of Wales. Taken from ‘Album presented to Rev. Gwilym Davies - photographs of Peace Pageant on the Aberystwyth Castle Grounds, Wednesday 8 May 1935’, B6/6, National Library of Wales.

After these displays of conflict the narrative turned to those who had tried to stop war. The Hebrew prophet, Micah, walked into the arena and spoke to the audience, prophesising that eventually the time would come when men learned the futility of war, and would instead enjoy peace. The following incident was more thrilling; from opposite sides of the arena warriors marched in, one group representing the Romans and the others the Sabines. Just as they began to attack, a number of Sabine women rushed in between, forcing the hostilities to end. Married to Roman men, they realised that war between the two would inevitably mean the loss of husbands, fathers and brothers. This, according to the announcer, was an example of how ‘Throughout the ages, women have realised that war deprives them of those whom they love.’ Other episodes from the Roman period then followed; Vergil, the poet who saw the vision of a world at peace; and the abolishment of gladitorialism following the intervention of a fearless priest, who paid with his life by getting in the middle of a bloody contest. His sacrifice, ‘a single protest’, had the ability to abolish a custom which had endured for ages. Following the Romans was another religion-based incident, where the Pope persuaded Attila the Hun to not attack Rome – surely the only example of Attila the Hun and the Pope in a British pageant, not to mention in the same scene! A following scene where bishops and clerics persuaded medieval military leaders to make peace signified the same idea. Chaucer’s ‘parfait knyghte’ and then a company of Knights Hospitallers made much the same point, representing Christian ideals in fairness and courtesy in war, and mercy and tenderness in the care for the sick and dying repseftively. Dante Alighieri then walked across, the first to argue for, according to the announcer, a federate Europe living at peace but organised for war in defence of her ideals. William Blake then featured, invoked for his poem Jerusalem – ‘a clarion call to those who work for peace’. Florence Nightingale, along with her nurses, walked across to remind the audience of the women who ‘strove to ameliorate the barbarities of war by caring for the sick and dying’. John Bright, the Quaker, was acknowledged for his voicing in Parliament the Christian view that war is wrong, despite the excitement of the Crimean War.

Dante Alighieri. By permission of the National Library of Wales. Taken from ‘Album presented to Rev. Gwilym Davies - photographs of Peace Pageant on the Aberystwyth Castle Grounds, Wednesday 8 May 1935’, B6/6, National Library of Wales.

The final entrant was Henry Richard of Tregaron. Walking up to the Maen Log (Logan Stone), the announcer informed the crowd that Richard was

‘honoured throughout Wales as her great apostle of peace… [whose] peculiar contribution to the cause of peace to formulate as a practical policy an alternative to war – arbitration. And this formulation has been and is the foundation stone of all attempts made since his day to secure peace, to obtain justice between nations without recourse to war, and to employ might righteously. Henry Richard laid the foundations upon which all who come after him must build.’

The other historical characters now grouped around Richard, as the audience, led by the choir, was encouraged to join in the singing of Blake’s Jerusalem. Unlike most historical pageants, there was not a clear chronology to these ‘walk-on’s’; instead, episodes was organised thematically. The historical characters portrayed also had no specific relation to Aberystwyth, instead being chosen to signify attitudes across the past.

Henry Richard of Tregaron, surrounded by all performers. By permission of the National Library of Wales. Taken from ‘Album presented to Rev. Gwilym Davies - photographs of Peace Pageant on the Aberystwyth Castle Grounds, Wednesday 8 May 1935’, B6/6, National Library of Wales.

The second episode was an allegorical Ballet of War and Peace. It began with a large cauldron in the centre of the arena. Witch-like figures of Fear, Hatred, Jealousy, and Suspicion enter, and dance around the cauldron, chanting and throwing in flammable materials. A dancer representing Rumour swiftly enters into the arena, followed by War Maidens carrying unlighted torches. Rumour throws a spark into the cauldron. The contents burst at once into a great blaze. The War Maidens kindle their torches at the cauldron, as the witches dance in exultation. Suddenly the figure of Peace appears in the gate-way. She is attended by figures representing Industry, Commerce, Science, Art, as well as a number of her own maidens. There is a dance in which the torch is wrested from the War Maiden, and dashed out against the ground. The War Maidens lie where they fall, at the arena’s edge, while the Peace Maidens dance back to Peace. The extinguished torches and the defeated War Maidens remain at the edge of the arena. Peace stands in the centre, triumphant, mounted on the Maen Llog. Her attendants are seated, grouped about her. The maidens dance in a circle around the group, while doves flutter overhead.

Ballet of War and Peace. By permission of the National Library of Wales. Taken from ‘Album presented to Rev. Gwilym Davies - photographs of Peace Pageant on the Aberystwyth Castle Grounds, Wednesday 8 May 1935’, B6/6, National Library of Wales.

The final scene brought the action to the present day, when 1000 children, in the national dress of over fifty different countries, marched into the arena. The announcer introduced Gwilym Davies, and announced that, in ten days time, the Fourteenth Annual Message of peace would be broadcast to the world. To signify this moment in pageantry, the Rev Gwilym Davies then took his place at the microphone, and addressed the children of the world in front of him:

‘From our playgrounds, schools and homes we, boys and girls of Wales, greet the boys and girls of all the world. Springtime has come once more to our little country; springtime with all its loveliness in trees and flowers. And we children are of the spring, too; for through us the world becomes young again. Shall we, then, on this Goodwill Day, all join hands in a living chain of comradeship encircling the whole earth? To-day we would also remember with gratitude those, in all countries, who have renewed life and enriched it by conquering disease and who, by their labours, have brought health and happiness to mankind. Science has made us neighbours: let goodwill keep us friends.’

After a minute of silence, a child representative of each country mounted the Maen Log and thanked the children of Wales for the message of goodwill. The pageant ended with a representative of Wales crying to the assembled people:

‘Llais uwch Adlai -------- -----------A oes Heddwch?

Llef uwch Adlef ---------------------A oes Heddwch?

Gwaedd uwch Adwaedd --------- A oes Heddwch?’

The people assembled, together with the children gathered about the Maeen Llog to represent the peoples of the world, cry together: ‘HEDDWCH.’

Welsh children representing Southern China. By permission of the National Library of Wales. Taken from ‘Album presented to Rev. Gwilym Davies - photographs of Peace Pageant on the Aberystwyth Castle Grounds, Wednesday 8 May 1935’, B6/6, National Library of Wales.

Reception in the press was mostly positive. The Cambrian News waxed lyrical about the beauty of the pageant, describing it as ‘no mere pageantry of colour, but a lesson to the huge crowd which watched with intense interest.’ When the choir began to sing the ‘well-known strains of Jerusalem… there was across the expectant crowd a whisper of joyousness and a fervent Amen.’ But not everyone was thrilled. Particularly vociferous in their condemnation were a pair of students from the University College of Wales, based in the town, who described the whole event as ‘a glorious failure!’ Writing to the Western Mail letters page, their bone of contention was what they saw as anti-English sentiment and Welsh Nationalism, all the more deplorable as it was dressed up ‘in the guise of internationalism.’ Their first criticism was that, despite their being 50 countries represented in the final scene, ‘England was conspicuous by her absence.’ In a move that would raise the hackles of many a Welshman today, they finger wagged ‘we must not forget that Wales could do precious little for peace without the leadership of England.’ Now in a full-steam rant, they declared it appeared ‘characteristic of the Welsh to give credit where credit is not due and to withhold it where it is ’, by giving too much prominence to William Blake – ‘a third-rate poet, who endowed literature with a quantity of Superfluous versification [irony alert!] – John Bright – ‘whose contribution to peace is doubtful’ and, ‘to crown all’, Henry Richard, who was ‘unknown outside Wales.’ Whether these criticisms were fair or not, the point was clear: in any peace pageant, Wales should have been ‘content to take her due and humble place as a member of the family of nations.’

Despite the mumblings of some of the students from the University, the event seems to have been a grand success. Press reportage was positive; every souvenir programme was sold; and the castle ruins were clearly packed with spectators ‘probably the largest crowd which has ever assembled in the Castle Grounds’.

Tom Hulme