The Chelsea Historical Pageant 1908

‘Little Chelsea, in fact, is going to show greater London how the thing ought to be done…’

The Times (12th June 1908)

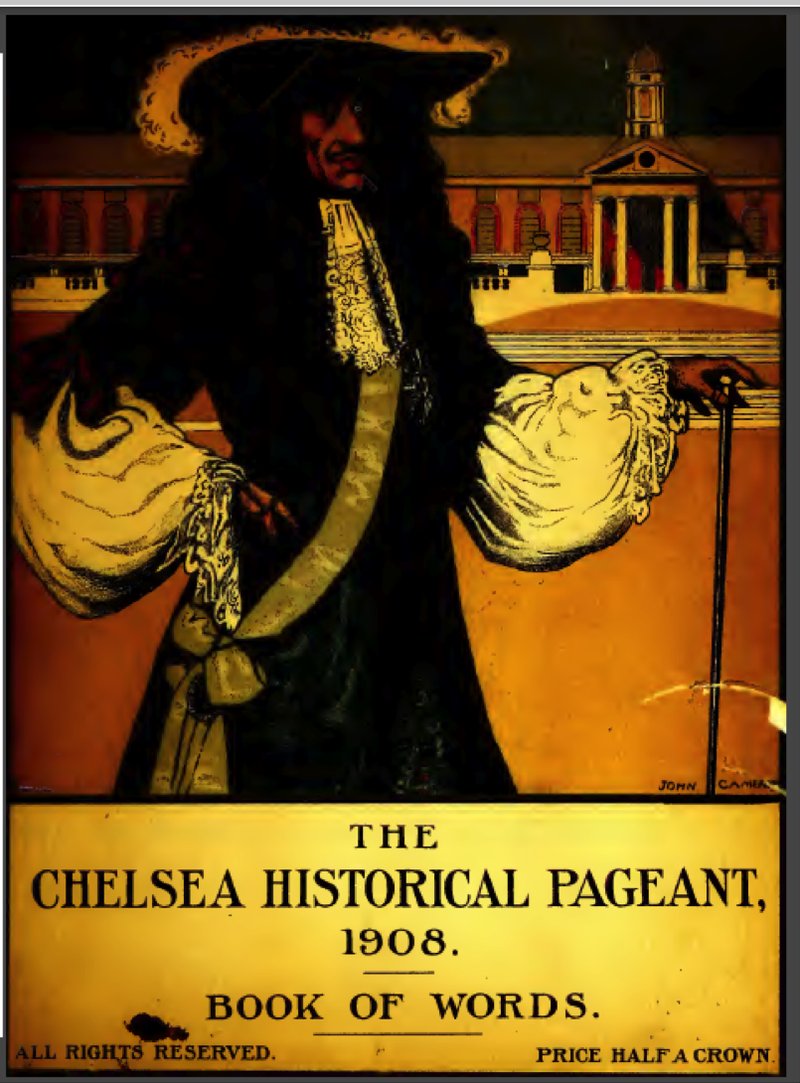

Taking place at the end of a fortuitously warm June in 1908, the Chelsea Historical Pageant was the first to take place in London as ‘pageantitis’ spread across the nation. For Chelsea’s pageant-master, J. Harry Irvine, and the medley of local lords, ecclesiastical figures and municipal dignitaries who organised the event, a grand civic celebration of Chelsea’s history could potentially inspire pride and love for the ‘ancient’ village in the present day. Organizing the pageant was a mammoth task, and took a year of careful planning. Each of the ten episodes was written by a different person, and based upon extensive historical research that aimed to provide a mostly faithful account of history. There were around 1200 amateur performers, each in dress made locally by women volunteers, and a general committee of almost 90 people. Along with the ‘monster’ grandstand that sat over 3000 people, from the roof of which Irvine conducted the pageant, there was an opportunity for almost all of the citizens of Chelsea to be involved. The potential for bridging social divides was not missed by the pageant organisers, nor The Times, who optimistically expressed their belief that Chelsea’s inhabitants had happily, and ‘without any distinction of classes’, worked ‘hand in hand, and shoulder to shoulder’. For Tom Heslewood, the primary costume designer, the experience was not so happy; the strain of creating this experience of ‘spectacular beauty’ was so great that he suffered ‘a rather severe breakdown’. Many worried that he might not be able to take his part of Charles II, but fortunately he pulled through, and performed his role in Episode VIII as the founder of the Chelsea Hospital in 1681.

Most of the episodes were chosen to illustrate the importance of the riverside village to nationally significant events that had occurred throughout the previous thousand years. It was at Chelsea that the Romans crossed the Thames in 63 B.C., the druids being met by a confident Julius Caesar; in a Chelsea garden that Henry VIII urged Thomas More to take up the poisoned chalice of Lord Chancellor; at Chelsea Manor House where Elizabeth I precociously articulated her desire to rule, and the funeral of Queen Mary departed; and at Ranelagh Gardens, also the actual location of the pageant, where the performance culminated in a grand Royal Fete in 1749. The significance of all these events was carefully detailed in the accompanying book of words, lavishly illustrated and available to purchase for half a crown. As the epilogue to the pageant implored:

Is it not well that we, the ages’ heirs,

Should waken Chelsea’s pride in Chelsea, thus

To realise how every yard of earth

About her homes is charged with memories?

To watch, as in a glass, how history

Is builded, aye, and building, hour by hour.

And we its architects?

Roman soliders of Episode 1

Henry VIII and Thomas More

Episode X: Royal Fete at Ranelagh Gardens in 1749

Episode 1: The Romans cross the Thames at Chelsea, 53 BC

If the purpose of the pageant was to inspire Chelsea’s residents, laughter was certainly not out of the question. The inclusion of processions from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1590) especially meant that there was an opportunity for fantastical figures in outlandish costumes to parade around the pageant grounds. The giant Orgoglio made an appearance, grotesquely looming over the other actors around him, and a dubious looking-lion, most likely a costumed child, was captivated by the beauty and innocence of Una. In Episode III the jolly villagers, and their seemingly not-so-jolly looking children, danced around the Maypole, performed the chronicles of Robin Hood, and even cheered on a fight between a dog and a bear.

The giant Orgoglio, from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen, in Episode VII

Episode III: May Day children

Appealing to the coarser whims of the audience, the final episode provided a moment of pure slapstick comedy. The scene was the Royal Fete of 1749, attended by Charles II and other local and national notables. John James Heidegger, Master of Revels and the organiser of the fete, rushed around nervously, and exhorted the orchestra to strike up the national anthem. Unbeknownst to Heidegger an imposter had been snuck in by the scheming playwright David Garrick and his accomplice the Duke of Montagu, who proceeded to dress the man in an identical style to Heidegger, complete with a mask of his face. While Heidegger sycophantically ingratiated himself to the King, Heidegger’s double mischievously instructed the orchestra to play Charlie Over the Water. In the ensuing confusion and mock anger of the King, who was also in on the gag, Montagu, barely containing his laughter, pointed his guards to the real Heidegger and ordered them to ‘run the traitor through’. As the Book of Words described:

The officers threaten Heidegger with their swords, one of which pricks him in a certain place behind. Heidegger jumps, and clasps his hand there… glaring round at the laughing faces, he rushes off, one hand on his wound, and his wig all awry, amid general laughter.If Irvine and the rest of the organisers thought the combination of fun and instruction through pageantry spectacle would awaken the civic conscious in all the people of Chelsea it seems they were perhaps mistaken. One gentlemen who clearly missed the point was Charles Fairplay. Ejected from the pageant for reasons unknown, he didn’t go quietly – dislocating the hand of one constable and punching another heavily in the jaw. While he was remanded at Westminster, it seems many found other things to do. While the The Times waxed lyrical about the content of the performance, it still lamented that ‘…audiences have not been as large as the excellence of the pageant deserved.’ With the combination of expensive ticket prices and a whole host of other attractions taking place in London at the same time, like the Horse Show or the Franco-British and Hungarian Exhibitions, the pull of the pageant was not strong enough to give even one sell-out night. Consequently it only made about £700 in profit, donated to the local charities. Maybe the three-hour extravaganza covering 800 years was simply too complicated. G.K. Chesterton, that most astute of commentators, and a pageant performer himself, thought the Chelsea Pageant ‘excellent’, but wondered ‘How many people actually living in Chelsea… ever even knew that Lord Chesterfield or Richard Steele had set foot in the place?’ In his opinion it would ‘probably have been a better piece of pure localism if they had relied on more recent memories’.

Yet the pageant was still undoubtedly important, and a watershed moment in the wider movement kick-started by the Sherborne Pageant of 1905 – not least for the many women who took part. While the primary committee of Officers of the Pageant was dominated by men by 10 to 1 – the only woman taking the role of Mistress of the Wardrobe, the Executive Committee and General Committee were almost 50-50. Perhaps more surprising is the photographic evidence that suggests St. George, who was part of the Faerie Queen Masque in Episode VII, was played by a young woman. Even more surprising, the official photographer was Kate Pragnell – the second professional female of that trade in London, and unusual in her success at gaining contracts from men at a time of antagonism. These facts, as well as the inclusion of strong female roles like Elizabeth I, may suggest that contemporary political issues like womens suffrage had crept into the Pageant as well – though whether the audience recognised this or not we can only speculate.

Elizabeth I

Una, the Lion, and a female St. George

While maybe not the unbridled success the elites of Chelsea hoped, now 105 years old, the Pageant has not disappeared from public memory. In its centenary year of 2008 a new Chelsea Pageant was performed at the Royal Hospital, the first in the grounds since its Edwardian predecessor. Produced by Christopher Joll, who also created the successful Household Cavalry Pageant in 2007, the President of the pageant was Earl Cadogan – great grandson of the 1908 President. For two nights only, in front of a packed crowd of 3500, spectators were taken through the life of the Royal Hospital, beginning with its founding by King Charles II, also an episode in the original pageant. Voices of historical figures were provided by famous actors like Dame Judi Dench, Rory Bremner, Timothy Spall and Joanna Lumley, and the whole event was narrated by former MP Michael Portillo. Music from the period was provided by the Household Cavalry’s State Trumpeters, the Band of the Life Guards and the Choir of the Royal Hospital, and the pageant finished with a large firework display. While this event was perhaps targeted more towards raising funds for the Chelsea Pensioners’ Appeal than constructing ‘village’ civic unity in the 21s Century, pageantry lives on in ‘Sweet Chelsea by the River’.

Images by kind courtesy of the Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies Library.