Chilham Castle Pageant 1946

The pageants that were held immediately after 1945 were suffused with the weight of that monumental event. Chilham Castle is a large Tudor-style manor house that lies between Ashford and Canterbury in Kent. Like many stately homes, it had been occupied by the army during the Second World War, and had been bought by the colourfully named Somerset de Chair, a politician, author and soldier in 1944.[1] De Chair had lost his seat for South West Norfolk in 1945, losing by 53 votes and was at something of a loose end, in his own words: ‘I felt sorely treated by the election and other disappointments’.[2] De Chair attended a Kentish appeal for the National Association of Boys’ Clubs ‘and rashly offered to hold a pageant at Chilham. I had no idea what I was in for.’[3] A local producer, Edie Craig, who was a daughter of the famous Edwardian actress Ellen Terry, was recruited, who ‘agreed to produce the pageant for the cost of re-thatching the barn, which in those days was £100.’[4] Craig, was well-versed in pageantry, going back to the Suffragette Pageant of Great Women (1910). As de Chair recounted: ‘It was a nightmare getting ten or a dozen villages to act ten or a dozen episodes. But they did it; and the long loft over the still disused cow byre abandoned by the army, was turned into a dressmaking establishment’.[5]

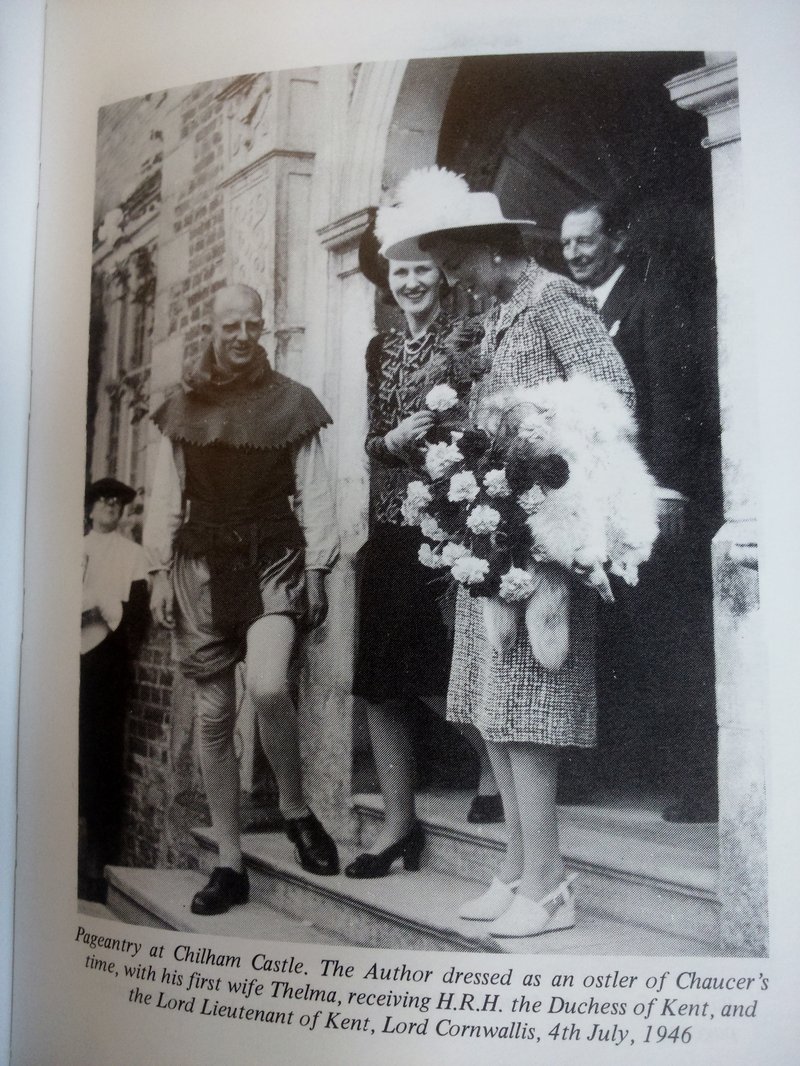

Above: A Plate from de Chair's memoirs Buried Pleasure showing the author dressed as the ostler receiving HRH the Duchess of Kent at Chilham Castle Pageant

The pageant was striking for the heavy involvement of Conservative figures who, in general, stayed aloof or even opposed to pageantry in the post-war period, castigating it as either an unnecessary expense or a trick of socialist propaganda. The local MP, Edward Percy Smith acted as the narrator, Geoffrey Chaucer, with de Chair playing the ribald ostler who conversed with him between each episode.[6] Ken Hardy, Chairman of the Kent County Council, played Sir Dudley Digges, the former owner of the castle.[7] Smith, who stood down at the 1950 election, may well have been presenting de Chair as his potential successor. In fact, the local Conservative Association bought fifty five shilling tickets for the opening performance, with the Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald announcing: ‘It is learned that this outing is expected to be the forerunner of others in the Conservative Association’s new drive to increase membership.’[8]

De Chair had enjoyed a stellar political career, becoming an MP at the age of 24 having published books predicting the Second World War and the spread of communism, becoming Parliamentary Private Secretary in 1942 after distinguished service in the Middle East.[9] The post-war period saw de Chair, an avid historian and art collector, at something of a loose end, with his meteoric rise momentarily arrested. One can very much view the Pageant as a device for taking his mind off things. The Pageant, which he wrote, was a classic account of the place’s importance in wider history, experiencing the myriad of invasions and Royal visitations. A significant device was the deployment of two narrators, Geoffrey Chaucer (local MP) and the Oastler of a local tavern, who presented all the dialogue. This is one of the earliest uses of a narrator; a tradition which became widespread in postwar pageantry. The inclusion of Chaucer, the scene adapted from the Canterbury Tales, the scene with Jane Austen, and a reading of Rudyard Kipling’s ‘If you wake at midnight’ in the smuggler episode was a nod to de Chair’s literary pretensions (he also wrote novels).

One of the biggest coups of the Pageant was the patronage of the Duchess of Kent, who opened the Pageant and drew wide newspaper coverage, particularly from the Times,[10] with the Bury Free Press praising de Chair’s script, fondly recalling the recently-dismissed local MP.[11] The Pageant was widely praised, with the Times calling it ‘outstandingly successful not only as an excellent entertainment but also as a means of aiding the Kent appeal’, in the ‘ideal setting for a pageant of Kentish history’.[12] The newspaper, generally rather sniffy about local pageants, praised the performers themselves: ‘One felt indeed that this pageant was as much an enjoyment to these performers as it was to those who watched them,’ and noting the ‘the obvious pride in the place that Chilham can claim in our island history.’[13] The Dover Express noted that the pageant was ‘mimed with a perfection which reflected the greatest credit not only on the members of the cast, but also upon those in whose hands had been entrusted the difficult task of production and rehearsals.’[14]

The scene which got the greatest applause was the final scene, in which Lieutenant M.E. Clifton-James played Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. In fact, Clifton-James had acted as Montgomery’s double shortly before D-Day in Operation Copperhead where the pay-clerk was farcically employed by David Niven to impersonate the Field Marshal to divert German attention during the weeks before the Allied landings in Normandy.[15] Clifton-James’ book I Was Monty’s Double (1954), which was turned in to a film in 1958, detailed these exploits. Whilst it was generally rare to portray a major living figure in a pageant, the scene obviously appealed to the audience for whom the war was still fresh in their memories. When promoting the film, Clifton-James’ wrongly told the Sarasota Herald that the audience at the Pageant had believed that Clifton-James was the real Montgomery.[16]

The Pageant was a great success, attracting 10000 attendees and making £2717 profit, which was divided equally between the National Association of Boys’ Clubs and the Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen’s Families Association[17][18]

[19]‘beautiful

medieval maidens wearing wimples’, who yielded £400, and judging a contest of

the ‘fleetest maid’, ‘won by the head gardener’s beautiful daughter Rosemary

Verral amid general acclaim’, and suggesting he might exact his seigniorial

duties upon her.[20]

[21][22]

[1] ‘Somerset de Chair’, accessed 3 May 2016, http://www.chilham-castle.co.uk/somerset-de-chair/

[2] Somerset de Chair, Buried Pleasure (London, 1985), 127; ‘Death of a self-confessed heterosexual’, Independent, 15 January 1995, Accessed 3 May 2016, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/death-of-a-self-confessed-heterosexual-1568079.html

[3] de Chair, Buried Pleasure, 128.

[4] Ibid, 128.

[5] Ibid, 128.

[6] Ibid, 128.

[7] Ibid, 128-9.

[8] Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald, 22 June 1946, 5.

[9] ‘Death of a self-confessed heterosexual’, Independent, 15 January 1995

[10] Times, 6 June 1947, 7.

[11] Bury Free Press, 7 June 1946, 4.

[12] Times, 6 July 1946, 2.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Dover Express, 12 July 1946, 9.

[15] ‘The impersonation of General Montgomery’, Spokesman Magazine, January 2005, accessed 3 May 2016 https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-135759761.html.

[16] Sarasota Herald Tribune, 23 November 1958, 68.

[17] Times, 14 November 1946, 7. Accessed 3 May 2016, ‘St Albans 1948: an austerity pageant’, http://www.historicalpageants.ac.uk/featured-pageants/st-albans-1948-austerity-pageant/

[18] de Chair, Buried Pleasures, 130.

[19] ‘Somerset de Chair’, accessed 3 May 2016, http://www.chilham-castle.co.uk/somerset-de-chair/

[20] de Chair, Buried Pleasures, 129.

[21] ‘Death of a self-confessed heterosexual’, Independent, 15 January 1995.

[22] Accessed 3 May 2016, http://www.chilham-castle.co.uk/the-history-of-chilham-castle/