A Grand Celebration of Border History: The Carlisle Great Historical Pageant.

Carlisle was a bit of a late arrival to the pageant craze of the early twentieth century. After all, between the advent of modern, historical pageants at Sherbourne in 1905, and the year 1928 when Carlisle finally took the pageant plunge, possibly hundreds of such outdoor events had already been held across the length and breadth of Britain, not to mention elsewhere in the world. Perhaps no big local anniversaries had occurred with which to justify the occasion of a historical pageant; or maybe hard-working Cumbrian citizens did not countenance time away from all their industry to organise this type of labour-intensive entertainment. We can only speculate... but perhaps a reasonable guess for the absence of a pageant until fairly late in the day is that history was simply everywhere in Carlisle and may have been taken a little for granted in this Border city.

As one civic dignitary put it, Carlisle 'was the cockpit of the wars of the Borders'. From the Romans to the Jacobites, the leavings of a succession of invaders were all too evident and undoubtedly had been incorporated into local identity as an aspect of everyday life within England's most northern city. If we accept there may be some truth in this particular analysis, what then did make Carlisle turn to pageantry in 1928?

Carlisle En Fete!

It was, in fact, the growing trend among Britain's industrial towns and cities for holding a 'Civic Week' that encouraged Carlisle to start planning its own historical pageant. During the interwar economic crisis, these festivals were designed to highlight local manufacturing and attract attention to the successes of civic enterprise. Carlisle was proud of its industrial prowess and intended to hold its own manufacturing showcase in the summer of 1928; this was to be headlined by an industrial exhibition where local engineering, textile, and bakery companies, among others, proudly displayed their wares. Within wider plans, at first, the pageant was only one of many planned Civic Week attractions. A good number of British pageants were held in tandem with Civic Weeks, so here again Carlisle was doing nothing new. Yet, having come to the pageant trend later rather than sooner, the Carlisle Great Pageant (as it soon became dubbed) was certainly designed to make a large impact. A will to impress ran through this pageant from the very beginning of its organisation in April 1927. Such were the efforts made, that by the time it was performed at the start of August 1928, a barely disguised and widespread view was taken that the pageant easily took the prize for being the premiere event of Carlisle's en fete Civic Week. For due to a brilliant publicity initiative and a high level of local enthusiasm, other draws such as a huge firework display , a fancy dress ball, decorated streets and an elaborate torchlight tattoo, came nowhere close to the cachet of the pageant.

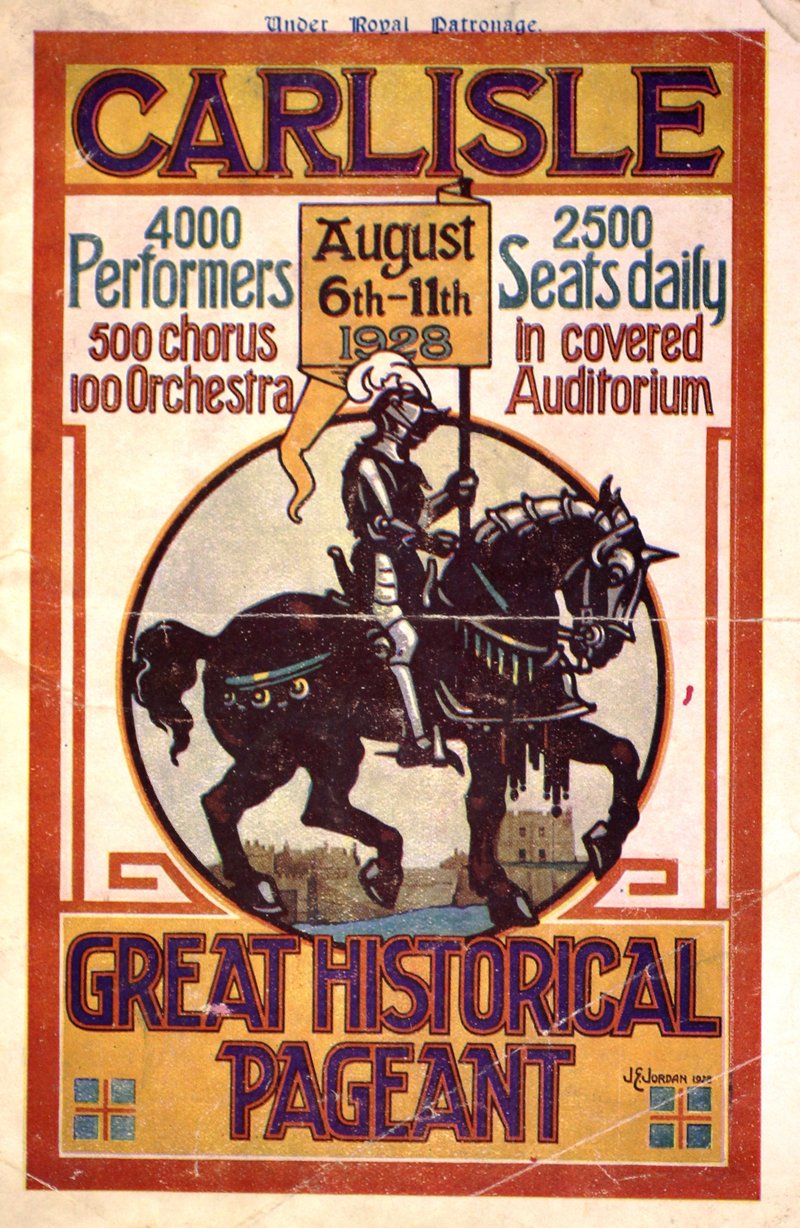

Cover for one of the many promotional programmes produced for the Carlisle pageant in 1928.

The view that the pageant simply outpaced everything else in Civic Week was not misplaced. Even in a year that had seen the widely publicised financial disaster of the city of Glasgow's massive pageant, held in June 1928, the organisers in Carlisle never lost their nerve. Carlisle's pageanteers started with big ambition and they kept going at this pitch. No stone was left unturned in the effort to advertise this celebration of Border history to the widest possible audience and right up until a couple of weeks before dress rehearsals began, recruitment of performers to make this huge display even more spectacular was still going on. In the end, 4000 took part - a very considerable achievement for this relatively compact city - and one that demonstrated the passion at large for telling Carlisle's colourful story.

Pageants the length and breadth of Britain aimed to be inclusive and Carlisle took this obligation seriously by encouraging all of its citizens to play their part in some way. Even the very young joined in with the pageant! These performers appeared in episode IX which depicted the Carlisle Great Fair at the start of the nineteenth century. The woman's costume (including the bonnet!) is still preserved at Tullie House Museum.

A Right Royal Occasion.

When planning for the pageant first began, an early indication of the city's ambition for the event was success in securing the services of the most famous pageant master of the day - Frank Lascelles. Having achieved this, a 'Royal Box' was also built into the plans for the arena. Royalty did not always shore up at pageants, even very big pageants, but Carlisle was optimistic on this point and that confidence was rewarded when Princess Mary agreed to attend a performance. The third augur of box office success was that a cluster of the great and the good promised their services to the pageant: most famously, the much-photographed Lady Carlisle agreed to play in the star dramatic role of Mary Queen of Scots within episode VI. Carlisle, without doubt, aimed high and was prepared to put in the maximum amount of effort that was needed for creating pageant magic.

One of the many souvenirs produced to commemorate the visit of Princess Mary to the Carlisle Great Pageant in 1928. This is a paper napkin wonderfully preserved at Tullie House Museum in Carlisle.

Lady Carlisle looking suitably tragic in the role of Mary Queen of Scots.

Organisation With Military Precision.

The organisation required to stage such a large, open-air event needed capable leadership. The pageant was headed by a 'Grand Council', which had around 100 members and included many individuals from local and, or, interested aristocracy such as the Earl of Carlisle, Lord Rochdale, Lady Anne Bowes Lyon and Lord Henry Cavendish Bentinck. Also part of the membership was no less than eleven armed services' officers including a Brigadier-General and two Colonels. The Grand Council was, however, more a vehicle for lending prestige than a hands-on body of organisers. Fourteen separate committees, each of which looked after a distinct part of the Civic Week and the pageant's activities, as well as nine individual committees in charge of each episode in the pageant, all did the real work. Within these, everything from finance and publicity to the practical arrangements needed to set up a substantial grandstand for housing the anticipated huge audiences was an allocated task that was tackled in detail by a designated committee. Carlisle had long been famous as a military garrison, so army and ex-army personnel proved immensely useful for much of the workaday but necessary administration involved with putting on a pageant. Men of the cloth also played a big part; but lest it be thought that pageant organisation was something of a male bastion, it should be noted that the women of Carlisle also fulfilled an essential (although often unsung) role. Most notably, episode IX of the pageant, which celebrated Carlisle's ancient Great Fair and had perhaps the biggest cast of all the episodes, was almost entirely organised by the local branch of the National Council of Women.

Clergymen were very active in pageant organisation, but as we see here, they also took performing roles. 'Father Time' was the pageant narrator in 1928 and was played by a high profile church minister.

An activity demonstrating 'common citizenship in a healthy and pleasant way'.

The Chairman of the pageant committee - Reverend T. B. A. Saunders - used these words to describe the purpose of Carlisle's pageant. What he meant by this was that the Civic Week needed to prove there was more to the city than just its industries. Saunders had the vision of providing a show that was both entertaining and educative but more importantly, would bring Carlisle citizens together in a demonstration of collective local pride. Certainly, with Frank Lascelles in charge, great numbers of people were needed. Lascelles made his mark on the pageant world by producing performances that depended on visual spectacle with huge casts, spectacular settings and lavish choreography. This meant that the script itself was definitely of secondary importance. To some extent, his approach was a pragmatic one, for before the widespread use of effective amplification it is unlikely that the majority within pageant audiences would have heard much of the words spoken. Perhaps for this reason, the task of scriptwriting for the 1928 pageant was first given to an amateur, though he was certainly someone with a public profile in the city. Mr J. S. Eagles, then general manager of the city's infamous State Management Scheme was appointed as the pageant's scriptwriter in 1927. Undoubtedly, Eagles set about writing with a will, but in truth, it is probably just as well that the success of the pageant did not depend on his script! The somewhat worthy verse produced by Eagles was rescued however, when a well-known and respected local historian - W. T. McIntire - was brought on board following Eagles resignation as State Scheme Manager and his relocation to London; it is notable that the episodes in which the new writer had a hand have a rather lighter touch and include some comic moments.

Lascelles too was unable to see Carlisle's pageant through to completion; he became ill during rehearsals and had to bow out of overall control, but the great pageant master had already made his mark, and had sufficiently inspired local organisers to carry on with the project as he had envisioned it . The scale of the spectacle won the day. Around 4000 local people including a 500- strong massed choir rose to the challenge of presenting Carlisle's history over nine episodes. A 100-piece orchestra further heightened the drama - playing both classical and traditional tunes. Together this ensemble dramatised the city's story in a way that really needed no words.

Presenting Border History.

The typical pageant of the 1920s began with an episode centered on Roman Britain, which meant that Carlisle was certainly under no pressure to defer from this well-worn path. For in terms of the history of the Romans in these Isles, the star location is undoubtedly Hadrian's Wall, and since it was thought that the Wall had in fact once run over the land where the pageant was to take place, the opening episode was given a special air of authenticity. This location was Bitt's Park, nearby to Carlisle Castle, the landscape of which was said to provide a 'natural arena'. Local railway workers played the Romans. This was perhaps especially fitting: for if the Romans had been responsible for putting Carlisle on the map in centuries past, it was the railways that had performed this role in more recent times, transforming Carlisle into a manufacturing and transport hub within the north.

Episode II, however, presented a bit more of a challenge. In this, historical accuracy was discarded in favour of a tale of the mythical King Arthur and his Knights. These legendary characters took on the mantle of defenders against barbarism - in the shape of the Picts from the north - who in this particular piece of drama threatened to take over Carlisle by breaching the unmanned wall following the departure of the Romans. The local Border Regiment enthusiastically played the vicious Picts. Fanciful though this episode was it seems to have had an allegorical purpose in that it underlined the extreme vulnerability of border settlements and the consequent need for strong defences. Moreover, at the end of the episode the wizard Merlin predicted that although Arthur had come to the rescue on this occasion, in the future others could and would successfully conquer, but that the spirit of Arthur would always remain ready to ‘awake in the hour of utmost peril’. This message was perhaps especially meaningful only a decade after the Great War when the protection of British interests had caused so much sacrifice, but the need to carry on defending these across the empire remained an imperative and depended on a strong level of patriotism. It is also the only, albeit oblique acknowledgement, in the pageant of this most recent conflict, which had taken the lives of so many Border citizens. From then on the pageant returned to firmer historical ground with a cavalcade of chronological tales that unfolded Carlisle's often-turbulent past.

The murderous Picts played with no small amount of enthusiasm by members of the Border Regiment.

The influence of Christianity was dealt with in episode III via the locally and nationally significant figure of St. Cuthbert; at the outset of planning it was suggested that Roman Catholics take charge of this scene. However, this proposal was rejected in favour of a non-denominational approach: perhaps telling us something about possible tensions that existed, following many decades of in-migration to the city as its industries expanded. Indeed, there was an accusation following the pageant that anti-Catholic bias was present in the script. Still, the episode did have a celebrity figure as its organiser: Lady Mabel Howard took on this task, and also played the central role of the Abbess of Carlisle. Likely, it was her social status that also encouraged many 'County Ladies' to play the parts of nuns.

Episode IV on the Norman Kings had less exalted leadership and was organised by local schoolteachers. In this, the English identity of Carlisle was the driving force. The ascendancy of King Henry and the importance to the monarchy of Carlisle’s position as a fortress was allegorically depicted with the building of Carlisle Castle using stones from Hadrian's Wall in the foundations of this new structure. This powerfully characterised the beginning of a different era in which Carlisle became a key frontier town for the English nation. Of note also in the telling of this story, is that it was Flemish builders who were shown to be in charge of this task; this was a further allusion to the city's ancient but continuing ability to absorb many incomers in the interest of commerce and was a turning point in the overall narrative of the pageant . For the remaining episodes, excepting the final one, the drama concentrated on conflict of one type or another with the Scots.

![]()

Friction with the Scots in the past was a theme of the pageant. In this postcard image of episode V, two kinsmen of Robert the Bruce are sentenced to death by Edward I.

Even so, as the narrative developed over five more episodes, the accommodation that was eventually reached with the Scots was shown to be to the benefit of all. This was most forcefully depicted in episode VII through the colourful tale of the Scottish Border Reiver, Kinmont Willie. Sir Walter Scott had previously made this real historical character into more of a legendary figure through his verse which told of Willie's capture and escape from Carlisle Castle. Taking its lead from Scott, in the pageant's version of this adventure, Willie was shown respect for his gallantry by his English foes. Moreover, though the infamous reiver escaped his English captors and lived to raid another day, the unruly Scots were shown to have been tamed by this experience. For in a variation on the usual tale, the pageant depicted Willie making his peace with a rival reiver family (the Elliotts) by allowing his daughter to marry into this clan. A similar capitulation characterised episode VIII centred on Charles Edward Stuart's disastrous rebellion in 1745 when the central Scottish character of 'Jimmy' deserted the Highland army in Carlisle and declared himself henceforth ' a loyal Hanoverian'. This ascendancy of British identity was emphasised in the final episode that depicted the folksy, traditional atmosphere of the Carlisle Fair on the eve of industrialisation. The scene involved a runaway couple on their way to Gretna to be married who had run into difficulties: but coming to the rescue was the quintessential northern Englishman, John Peel. Interestingly however, in this episode, members of the Dumfriesshire Hunt and their hounds accompanied Peel. So the pageant ended nicely with co-operation coming from across that troublesome border!

In episode IX, John Peel came to the rescue arriving at the Carlisle Fair just in time to help an eloping couple make it onwards to Gretna Green.

The First of a Trio.

In the Official Souvenir Book, the Pageant Committee Chairman - Rev. Saunders - commented in the foreword that 'there is a real danger, in these hustling days, lest historical memories should fade out of sight...' There was probably never any real danger that this would happen in Carlisle: for as the Lord-Lieutenant of Cumbria, Lord Lonsdale, who performed the opening ceremony on the first day, proclaimed, no city had more ‘right to a pageant’ than Carlisle. Here was a 'stirring and romantic story' he went on to state, and the pageant gave 'a birds' eye view' of it. The citizens of Carlisle appear to have agreed.

Carlisle's pageant was a highly successful celebration of local lore. It also made a clear statement about the importance of Border history within the British national story. The sun shone on Carlisle while it was en fete, and a little over 78,000 people attended the six dress rehearsal and six official performances held during the first fortnight in August. This triumph brought in a tidy profit of £7,000 (worth around £300, 000 in today's prices). Clearly, although the bar was set high for the pageant, Carlisle's citizens more than scaled this. Moreover, it left a legacy - Carlisle would go on to hold another two large and successful pageants in 1951 and 1977 - within two very different eras for the city, its industries and its people.

The majority of the images used are reproduced with the kind permission of Tullie House Museum

and Art Gallery Trust with whom the Redress

of the Past team worked closely on an exhibition which took place in 2015. More information about the exhibition can be found HERE