The Hertford Pageant of 1914

*Guest post by Philip Sheail - for more information on his book, click here*

The county town of Hertford is one of a number of historic English towns which during the Edwardian period, celebrated its millenary with a grand historic pageant. The Pageant took place in the grounds of Hertford Castle on six consecutive afternoons during the week of 29 June-4 July 1914. The performers numbered about 600, the audience totalled 6000, and the cost of staging it came to just under £2000. It was regarded by the townsfolk as a veritable triumph, but perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Hertford Pageant was the fact that it was ever staged at all.

Queen

Elizabeth I, her courtiers and the burgesses of Hertford in Episode VIII (The

visit of Queen Elizabeth to Hertford Castle, 1561). (Photo:

Hertford Museum).

Celebrating Hertford’s Millenary

Hertford was founded by the Saxon King Edward the Elder in the years 912-14. It lay at a crossing point on the River Lea which at that time formed the frontier between territories controlled by the Saxons and Danes. In time the settlement acquired the status of a Royal Manor. Then, later in the 10th century, when the country came to be organised into “shires”, Hertford became the county town of “Hertford-shire”. In the closing months of 1066, Duke William of Normandy established a motte and bailey castle beside the River Lea, just to the west of the town. It remained a royal stronghold and in 1170, during the reign of Henry II, it was considerably enlarged and upgraded. For about 300 years thereafter Hertford Castle was in constant use as a royal residence. The town itself was made a Royal Borough incorporate by William I and over the centuries its rights and privileges were maintained and formalised in a series of Royal Charters.

The Castle fell out of use as a royal residence in the early 1600s. The town fell on hard times for some years thereafter, but matters gradually improved during the 18th century and the town prospered as a centre for flour milling, malting, brewing and tanning. The railway stimulated further urban development and by 1914 Hertford’s population was about 10,400. Nonetheless, despite being an ancient royal borough and the administrative centre for the county, the town was much smaller than other urban centres in the county such as Watford, St Albans and Hitchin.

Amongst Hertford’s leading citizens in the early 1900s were two brothers, Robert and William Andrews, whose family had long been builders and timber merchants in the town. The brothers had a particular interest in local history and archaeology, and in February 1914 they achieved a long-held ambition to found a town museum. William had served on the Town Council since 1895 and in November 1913, at the age of 74, he was elected Mayor for the third time. No-one could have been better qualified or better placed to promote the celebration of Hertford’s millenary in 1914 than William Andrews. Indeed, on being sworn in as Mayor on 10 November 1913, he mentioned that next year would be Hertford’s millennial year – a unique occasion, he said, which he hoped would be observed “in a suitable manner.”

An ad-hoc committee of interested citizens had been formed during 1913, under the leadership of William Graveson, a draper and leading member of Hertford’s Quaker community. The committee garnered a great deal of information about the millenary celebrations held during the previous decade in places like Bury St Edmunds, Colchester, Coventry, Cheltenham, Winchester, Canterbury and Sherborne. In several cases these celebrations had taken the form of an historic pageant. The committee’s prime yardstick for such an event, however, was the mammoth St Albans Pageant held in July 1907, which had been performed on six consecutive days at the site of the Roman amphitheatre at Verulamium, had boasted a cast of 2000 and had been watched by some 23,000 people.

At the beginning of 1914, however, nobody in Hertford seems to have been promoting the idea of a millenary celebration with any sense of urgency. It was not until 27 January that William Andrews, as Mayor, called a public meeting to discuss the possibilities. Some 30 people attended, drawn mainly from the town’s more public spirited shopkeepers, brewers and builders, plus two clergymen and three schoolmasters. With his antiquarian hat firmly in place, Andrews opened the meeting by reflecting at length on Hertford’s early history and by stating his desire that the town “ought to celebrate its millenary in a suitable manner so that it would go down to posterity.” William Graveson presented a resumé of the information garnered by his committee. Andrews’ ambitions for Hertford, however, were very modest. In commenting upon the St Albans Pageant, he declared that “they could not hope to come up to that, as it would take a week to celebrate and entail an enormous amount of time and money in the preparation of it.” This view was initially accepted by those present at the meeting, and they proceeded to mull over the possibilities of holding a series of lectures on the history of the town and putting on a tea for the elementary school children in the town. It was acknowledged, however, that the townspeople would view such events as distinctly second rate, and they concluded that there was really no alternative but to stage some sort of pageant. From then on their ideas became steadily more ambitious and they began to think in terms of holding a two-day event at the end of June or beginning of July. They then formed themselves into a “Millenary Committee” and resolved to meet again the following week.

Photograph

taken behind the scenes at the Hertford Pageant. The two men in the foreground are courtiers

in Episode VIII (The visit of Queen Elizabeth to Hertford Castle, 1561) (Photo:

Hertford Museum).

The second meeting, held on 2 February, attracted far more people, but more importantly it was addressed by a guest speaker, Charles Henry Ashdown. Ashdown had been a teacher at the St Albans Grammar School, and was a man of wide-ranging interests, especially in local history. He had written the text for the St Albans Pageant while his wife Emily had served as Chief Mistress of the Robes. They had both enjoyed it so much that following Charles’ retirement from teaching in 1911, they went on to assist in the staging of pageants in various parts of the country. Thus when he came to address the meeting at Hertford, Ashdown spoke with considerable authority on the subject of historic pageants and, as the Hertfordshire Mercury commented, what he told them “as to the time, labour, and expenditure involved in the promotion of pageantry on anything like a grand scale upset all previously conceived ideas as to the nature of the undertaking on which they were prepared so light-heartedly to embark.”

He explained that pageants were notoriously expensive to put on and that a two-day pageant would not be a viable proposition. Under favourable conditions, they might clear their expenses with a three-day pageant. However, if they went for a six-day pageant, then “they ought to be rolling in wealth.” He also disabused the meeting of any notion that a pageant could be staged for a few hundred pounds. By its very nature a pageant required a cast of several hundred people, and their costumes could cost up to a pound apiece. In addition, there was the cost of staging and properties, of music, printing and advertising, and the fee of the Pageant Master and Mistress of the Robes. To meet such expenses, the St Albans’ guarantee fund had started at £2000 and had increased to £6000. Similar sums had been required for the pageant staged at Eastbourne. The Westcliffe Pageant had been a smaller affair and there the guarantee fund had started at £1000. It lasted a week and just about covered expenses. Thus, if the Millenary Committee wished to go ahead with a pageant, the first step would be to launch an appeal for members of the public to guarantee financial support. Then, if the takings failed to cover expenses, the organisers could call upon their guarantors to make up the shortfall.

Following Ashdown’s departure, the assembly elected an Executive Committee and charged it with the task of issuing a circular appealing for guarantees. During the following weeks the wisdom of staging a pageant became a subject of much debate amongst the townsfolk. The Mercury voiced the opinion of “some people” that pageants had lost their freshness and their power of attraction. Others thought that the town should mark its millenary with a memorial, such as a statue of King Edward the Elder, similar to the one of Alfred the Great which the people of Winchester had erected to celebrate their millenary in 1901. It is also evident, from comments made in the aftermath of the pageant, that there were a good many “croakers” who claimed that “sleepy Hertford” could never rise to the occasion.

A total of 1200 circulars was sent out, and when the Millenary Committee reconvened on 16 February it was reported that 80 replies had been received, of which 56 had expressed a willingness to become sureties, the total amount guaranteed being £578. The guarantors included the 4th Marquess of Salisbury who had made himself surety for £100 and had also agreed to serve as President of the celebration. In view of the short time which had elapsed since the circulars were sent out, the Committee considered the response to be most encouraging. The Mayor had also received detailed figures from Charles Ashdown which clarified the scale of the task before them. Ashdown estimated that, to stage a “small” pageant at the Castle would cost £1750, of which £350 could be recouped through the subsequent sale of materials. Thus about £1400 would be required, this figure to include a sum of £250 as the fee of the Pageant Master and Chief Mistress of the Robes. The Committee agreed that this figure, though substantial, was well within their grasp. The decision was therefore taken to stage a pageant in the grounds of Hertford Castle each afternoon of the week beginning Monday 29 June, and to invite Mr and Mrs Ashdown to act as Pageant Master and Chief Mistress of the Robes.

Photograph

taken behind the scenes at the Hertford Pageant, showing some of the performers

in Episode VIII (The visit of Queen Elizabeth to Hertford Castle, 1561) (Photo:

Hertford Museum).

Preparing for the Pageant

Having resolved to stage a full-blown “Pageant of History”, Hertford’s townsfolk had left themselves just four months in which to get everything ready. The Mercury later commented that this had caused everybody to work at top pressure, whether they were “an official, a member of the committee, a performer, or one engaged in the making of the costumes and properties.”

Venue and Organisation

The venue for both the preparation and performance of the Pageant was Hertford Castle. William Cecil, the 2nd Earl of Salisbury, had been granted possession of the Castle by Charles I in 1628, and it had remained in the hands of the Salisbury family ever since. For much of that time the property had been used as a grand private residence. Then in 1911 the 4th Marquess agreed to lease it to the Hertford Corporation for a period of 75 years at a peppercorn rent of 2/6d a year, the house to be used as municipal offices and the gardens as a public park. The grounds were formally opened to the public by Lord Salisbury on Saturday 27 July 1912.

The old house, known to all as “The Castle”, consisted of a 15th century gatehouse, plus an elegant wing added in the 1780s. The former bailey was given over to lawns and flower beds, and enclosed on two sides by a high wall made of brick and flint, which followed the line of the original curtain wall. The Town Council placed a whole suite of rooms on the second floor, plus some rooms in the basement, at the disposal of the Pageant Master and his co-workers. The Pageant itself would take place on the large lawn to the east of the Castle, while the spectators would be accommodated in a covered grandstand that stretched all the way round the east side of the lawn.

The Executive Committee remained in being, but under Charles Ashdown’s guidance, its work was supplemented by a whole raft of sub-committees who were responsible for such matters as finance, costumes, properties, music, casting, seating arrangements, the press, printing and advertising. At the same time the Executive Committee finalised the list of historical episodes to be portrayed in the Pageant. They were confined to the Saxon, Medieval and Tudor periods and comprised the following:

I: The Synod of Hartforde, A.D. 673

II: Defeat of the Danes by Alfred the Great, A.D. 896

III: Re-founding of Hartforde by King Edward the Elder, A.D. 914

IV: The Siege of Hartforde Castle, 1216

V: The meeting of King John of France and King David Bruce of Scotland, 1357

VI: Presentation of a Charter to Hertford by Margaret of Anjou, Queen of King Henry VI, 1451

VII: Suppression of Hertford Priory, 1533

VIII: Visit of Queen Elizabeth to Hertford Castle, 1561

Photograph

taken behind the scenes at the Hertford Pageant, showing the performers in

Episode II (The defeat of the Danes by Alfred the Great, AD896). The mounted figure is Alfred the Great. (Photo:

Hertford Museum).

Guarantors

The campaign to secure guarantors for the Hertford Pageant went on throughout the spring of 1914. Wherever a positive response was received, the Secretary would ask that person to complete a form on which they would specify the sum they were prepared to guarantee. The Committee also took out a public notice each week in the Mercury, which listed the names of people who had agreed to become guarantors and the sum guaranteed. The preamble to these notices was always very upbeat. It stressed the fact that the Pageant was most unlikely to incur a loss and that any surplus would be devoted to the permanent benefit of the Hertford County Hospital.

In conducting its appeal for guarantors, the Committee had its sights set not only on the more affluent citizens of Hertford but also on the titled aristocracy and gentry who between them made up the ranks of “County Society” in Hertfordshire. The notice printed each week in the Mercury was primarily aimed at such people. For whilst the notice served ostensibly as a scoreboard as to how the fund was progressing, in reality its prime purpose was to flatter the vanity of the guarantor and hopefully encourage his friends or social rivals to come on board. In certain cases, therefore, the sum guaranteed by an individual was of less note than his name, and such people were further flattered by being adopted as “Patrons” of the Pageant.

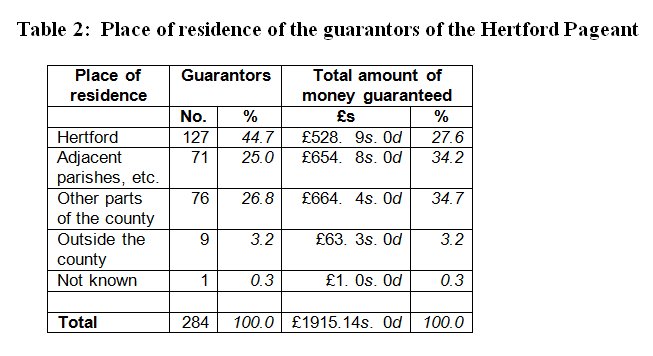

The Committee’s efforts were to prove successful. The guarantee fund, which stood at £500 in mid-February, rose steadily to over £1000 by 5 March and to £1700 by the beginning of April. It ultimately reached a sum of £1915. The Committee was also successful in securing support from members of County Society. At the final count the guarantors included a marquess, four earls, a viscount, 11 baronets; the High Sheriff, Lord Lieutenant, and the Chairmen of the County Council and the Quarter Sessions; 17 members of the County Council, 58 County Magistrates, 18 clergymen, and four MPs, including the member for the East Herts Division, Sir John Rolleston. The Patrons included all those guarantors who were members of the peerage, baronetage and knightage.

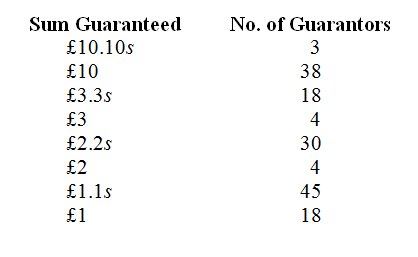

A prospective guarantor would select the sum he or she wished to guarantee from a range of categories set out on the form provided by the Secretary. Most people (23%) chose to guarantee a sum of £5. Those people guaranteeing a sum of less than £10 could chose from a wide range of categories. There was clearly a good deal of snobbery entailed in the matter of guineas or pounds, especially in the £1-£3 categories, as is demonstrated by the following figures:

The Mayor was the only Hertford resident to guarantee a substantial sum; of the other 126, 113 (90%) guaranteed sums of £9 or less. Thus the bulk of the guarantee fund was received from people living outside the Borough, the amount guaranteed being split almost equally between those people residing in the neighbouring town of Ware and in the parishes adjacent to Hertford, and those living elsewhere in the county.

Volunteer Helpers and Performers

The Committee made several appeals for volunteers to take part in the performance and to help with making costumes and props. These appeals met with a mixed response. The most ambitious part of the project was manufacturing the costumes, but there seems to have been no problem in recruiting sufficient women helpers. This was perhaps a measure of the under-employment which existed at that time amongst middle-class wives and daughters. Many of them clearly relished being involved in a project of this kind, and they were consistently praised for their dedication.

The

leading players in Episode VII (The suppression of Hertford Priory) – the Prior

Thomas Hampton and the King’s Commissioners.

(Photo: Hertford Museum).

The situation was rather different in the case of the men. Charles Ashdown was most insistent that the props should be as authentic as possible and whilst some of them might be made of papier maché, the armour and weapons had to be fashioned from metal and wood. There were plenty of craftsmen in the town with the necessary skills, and in late March they came forward in reasonable numbers. Many of them, however, failed to return after the Easter holiday. The reason for this is unclear, but it would seem that for many of the town’s craftsmen, the working day was quite long enough. Furthermore, once the evenings started to lengthen, they were easily diverted by sporting activities. The production of the props thus fell behind and at one point it looked as though the work would have to be completed by professionals, but somehow the Committee managed to resolve the situation.

Concerns also arose in regard to the performers. The original aim was to have a cast of 1000 people. The local thespians came forward very readily, but after the initial rush the numbers tailed off. By the beginning of May only 250 people had come forward. That figure included 150 students from Haileybury College, who had volunteered to serve as soldiers in Episode IV (The siege of Hertford Castle). Clearly, if the Committee were going to achieve their target, they would have to find a way of attracting people from across the social spectrum. For this to succeed, however, they would need to secure the active co-operation of the town’s shopkeepers and tradesmen, and that was no easy task. Any major public celebration disrupted the normal pattern of trade by drawing away customers and causing workers and shop assistants to ask for time off. Most tradesmen could cope with a celebration lasting one or two days, but a pageant lasting six days was a very different matter.

The

leading performers in Episode III (The re-founding of Hertford by King Edward

the Elder AD914). The mounted figures

are King Edward and his sister Ethelfleda, the Lady of the Mercians. (Photo:

Hertford Museum).

The Committee, therefore, made various overtures to the business community. They sought to demonstrate how beneficial a pageant could be to the town’s trade by stressing that all the materials used for making the costumes and props had been purchased from local suppliers, and that the printing of publicity materials had all been handled by local printers. They also stressed that, wherever a pageant was held, it brought hundreds of visitors to the town and that following the performance, they thronged to the shops to see the performers serving behind the counter in their picturesque costumes – a sight that was especially dear to Americans and visitors from the Continent. More importantly, however, the Committee worked with representatives of the local traders to find practical ways of addressing their concerns. One approach was to allow those workmen who wished to take part in the Pageant to put in overtime beforehand and clock up sufficient hours to compensate for the time lost during the performance. Another was to stagger the times at which employees needed to be absent and to arrange for parts to be shared between two or three people, thus reducing the number of days on which an individual would need to have time off.

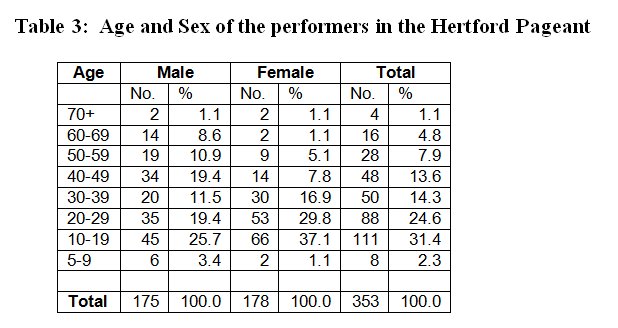

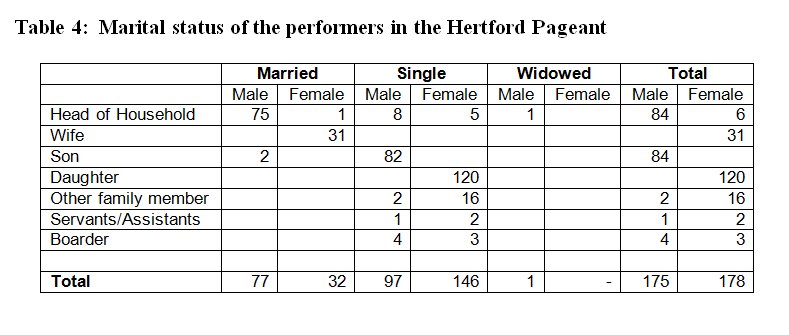

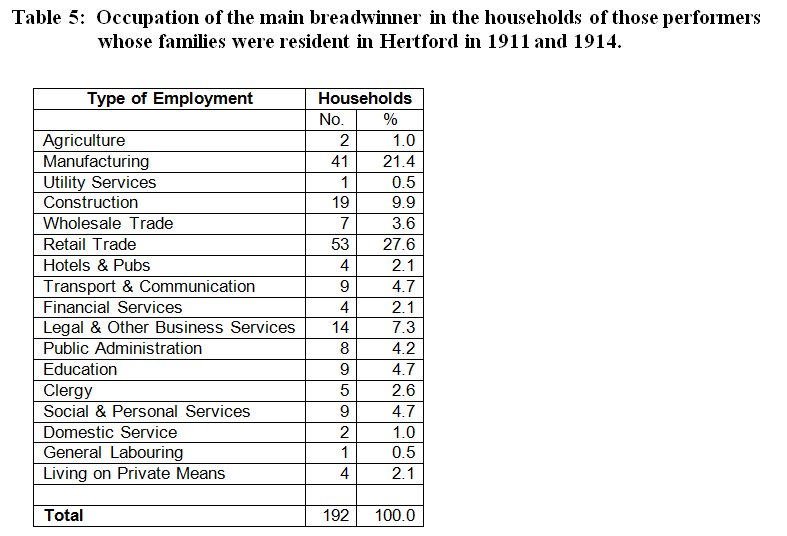

By these various stratagems the numbers coming forward to perform in the Pageant steadily increased, and the Committee eventually managed to secure the services of 469 men, women and children, plus some 150 students from Haileybury. This was subsequently trumpeted as a considerable achievement, whilst the original target of 1000 performers was quietly forgotten. Of those 469 persons, 354 (75%) have been positively identified in the 1911 census. Tables 3-4 provide details about their age, sex and marital status. Table 5 looks at their social standing, this being measured by the occupation of the main breadwinner in the family. For this purpose the table includes just those performers whose families were living in Hertford in both 1911 and 1914. They comprised 272 persons, who were contained within 192 households.

The Pageant performers were thus drawn primarily from the town’s shopkeeper and tradesmen class, and from families where the main breadwinner was a skilled worker, employed in one of the town’s flour mills, breweries and printing establishments. Hardly any came from the labouring class. As with any urban community at that time, Hertford was riddled with class distinction and petty snobbery. Thus, despite the broad social mix of the performers, there remained a fine distinction in status between, say, employers and their foremen, clerks and bench workers, or between the owners of the large drapery store and the small corner grocery shop or tobacconist. Most of these people had been brought up to recognise such distinctions and to show respect for their social superiors. Such ingrained habits would inevitably prevail in a situation where shop assistants and bench workers found themselves rubbing shoulders with the town’s leading businessmen and their families.

Furthermore, the themes explored in the Pageant tended to emphasise the hierarchical structure of society and the enormous disparities in wealth and power which existed between the highest and lowest levels. Apart from Episode VII (The suppression of Hertford Priory), each episode featured some grand royal personage, together with his or her courtiers and officials, and it was those personages who took pride of place in the scene. The more middling characters such as the Borough Reeve, Mayor, Bailiff and Burgesses generally occupied a supporting role. The most lowly figures, such as the Saxon peasants or medieval townsmen, simply made up the “crowd”.

The

men who served as the defenders of Hertford Castle in Episode IV (The siege of

Hertford Castle 1216) (Photo: Hertford Museum).

As a consequence of these different factors, the roles taken by the performers in the Pageant tended to echo their status in contemporary society. This can be seen especially with the persons chosen to represent royal personages. The part of Queen Elizabeth I was played by a member of the local gentry. Alfred the Great was played by Hertford’s Town Clerk and Solicitor, while other monarchs were played by leading businessmen in the district. There was also a certain drole sense of humour behind some of the casting, such as the casting of the Town Clerk, Alfred Baker, as “Alfred the Great” and his brother Herbert, a Major in the Hertfordshire Regiment, as Walter de Godardville, Governor of Hertford Castle during the siege. Several Councillors were cast in roles which echoed their status in 1914; namely, as members of the Saxon Moot and as the Bailiff and Principal Burgesses of Tudor Hertford. Such things would have been much appreciated by the audience. Furthermore, the roles of bishop or priest in the Pageant were all played by the incumbents of the town’s parish churches.

Pageant Week and After

The Hertford Pageant duly took place during the week of 29 June-4 July 1914. Apart from a heavy downpour on the Friday, the weather was magnificent throughout the week. The event had been preceded by considerable controversy over ticket prices, the cheapest tickets being 3/6d, and seems to have had an effect on sales, particularly on the Monday. However, the Pageant was deemed to have been a triumph overall and indeed the townsfolk clearly felt immensely proud of their achievement. The Executive Committee, in its preliminary report on the Pageant finances, struck a highly optimistic note. The weeks went by, however, and no final balance sheet was published. The reason for this delay was explained in the Mercury of 15 August. It appeared that certain claims had been received from “unexpected quarters” for services rendered. The Committee had been under the impression that these services were rendered on a voluntary basis, but this now appeared incorrect. Some of the claims were still under discussion and thus the exact amount of the deficit could not yet be ascertained. In the event no final balance sheet was ever published, for the whole matter came to be totally eclipsed by the outbreak of war on 4 August.

The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, occurred on Sunday 28 June, the day before Pageant Week was due to start in Hertford. The Pageant audience, like the rest of the British public, probably gave the matter little thought, assuming that it would all be sorted out in due course. The assassination, of course, was destined to have far-reaching consequences and a month after the end of Pageant Week, the country stood on the brink of a full-scale European war.

The war memorial at Parliament Square in Hertford bears the names of several men of the town who took part in the Pageant. Amidst the turmoil of the post-war period, the Pageant came to be remembered with a certain poignancy. Furthermore people everywhere began to feel a deep nostalgia for that long “Edwardian Summer”. They tended to forget the fierce controversies which had existed at the time and instead came to look upon the pre-war period as a golden age. And for the people of Hertford that golden age came to be symbolised perfectly in the grand historic pageant which they had worked so hard to put on and which they had all enjoyed so very much.