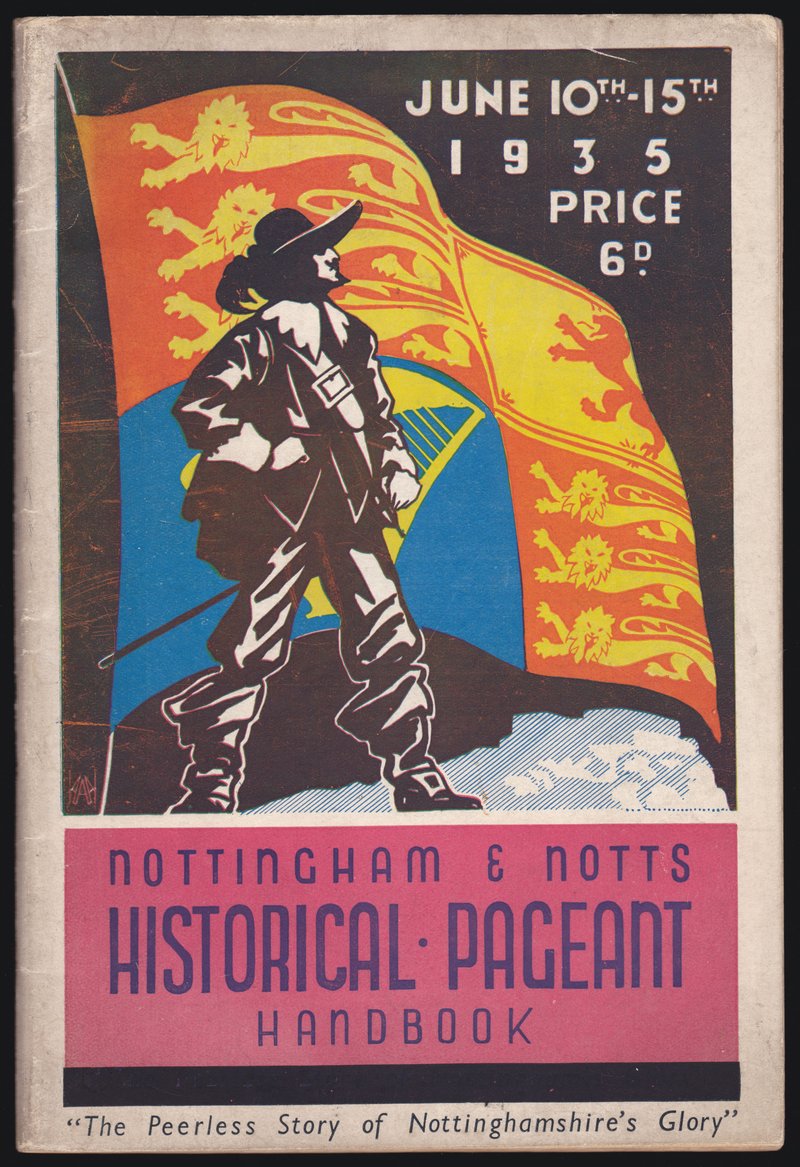

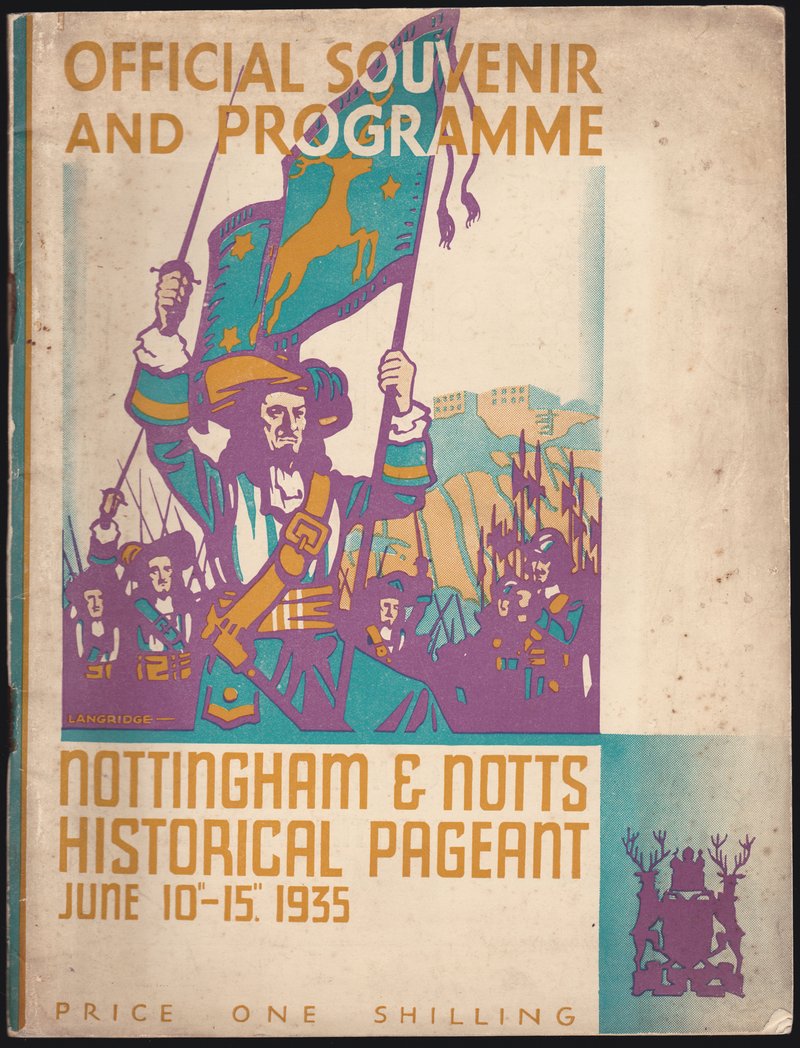

The Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Historical Pageant of 1935

*Guest Post by Tim Savage, Museums Officer for Harborough, Melton & Charnwood in Leicestershire*

The Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Historical Pageant took place in June 1935, in Wollaton Park. According to a correspondent writing in the Nottingham Guardian, the city’s effort was inspired by Leicester’s large successful pageant just three years earlier. But, in the context of the period, the pageant was yet another example of a large industrial city turning to popular pageantry as a way of promoting its local economy, with the bonus of stimulating a sense of community and continuity in a time of strife. After all, and in direct comparison to Leicester, Nottingham was faring badly during the economic downturn of the 1930s. In 1933, 20455 people were unemployed and workers’ wages were below what was seen as required for an acceptable standard of living; housing was in huge demand, due to population growth; and the industrial hosiery base of the city was declining. Thus, while the pageant was ostensibly staged to raise money for hospitals in Nottingham and the surrounding area, the fact that it also included an expansive Industrial Exhibition makes it clear that promoting the city – economically and socially - was a key factor as well.

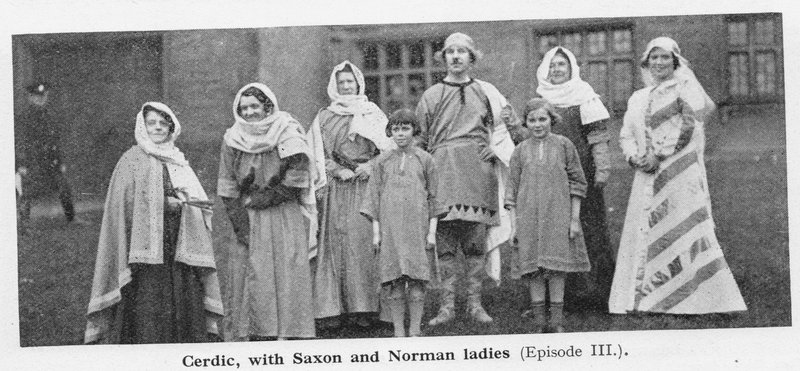

Edward Baring directed the pageant, with Nugent Monck as the producer – a role that seemingly more resembled the (perhaps by then) old-fashioned title of ‘pageant-master’. Both had extensive experience of creating historical pageants. Edward Baring had first become involved with the movement when working as a business manager for the Gloucestershire Pageant in 1908. In the interwar period he more commonly worked on historical pageants in big industrial cities such as Newcastle (1931), and especially with Frank Lascelles, such as Carlisle (1928) and Stoke-on-Trent (1930). Monck was an experienced theatrical actor and director, and had founded the Maddermarket Theatre in Norwich. He produced a Northampton Pageant (1926), as well as another Northampton Pageant (1930), a Wolsey Pageant in Ipswich (1931), and the Ramsgate Pageant (1934), amongst others. The executive committee included several civic worthies, such as the Lord Mayor of Nottingham, Sir Julien Cahn, and many other County Council members. A number of subcommittees, each with their own chair, boasted a wide range of figures from the city’s local civic culture, such as the Director of Education, the City Engineer and two professors from University College, Nottingham. Assistance from the county was sought, and people from Long Eaton and Mansfield produced Episode III.

The pageant took place in Nottingham, but – like Gloucester’s pageant in 1908 or Leicester’s in 1932 – the extravaganza was billed as being for the county as well. An official ‘County Day’ on 11 June was the centrepiece of this more inclusive focus. As the Nottingham Evening Post noted, ‘an unusually large section of the audience were people from outside Nottingham’ on this day. The organisers were also keen to make sure that the pageant had an even wider impact beyond the county. A huge number of civic dignitaries from across Britain were invited to attend the Civic Day on 12 June, including the Lord Mayors of London, York, Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, Bradford, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Grantham; various Sheriffs; Mayors and Mayoresses; and Town Clerks. The Lord Mayor of London and other civic guests were members of a huge procession around Nottingham, and a luncheon at which the toast ‘The City of Nottingham’ was made, before the pageant was opened in the afternoon. This local government focus reflected the attention being given to municipal administration and its achievements in the mid-1930s, as municipal officials and contemporary commentators reflected on the centenary of the Municipal Reform Act of 1835.

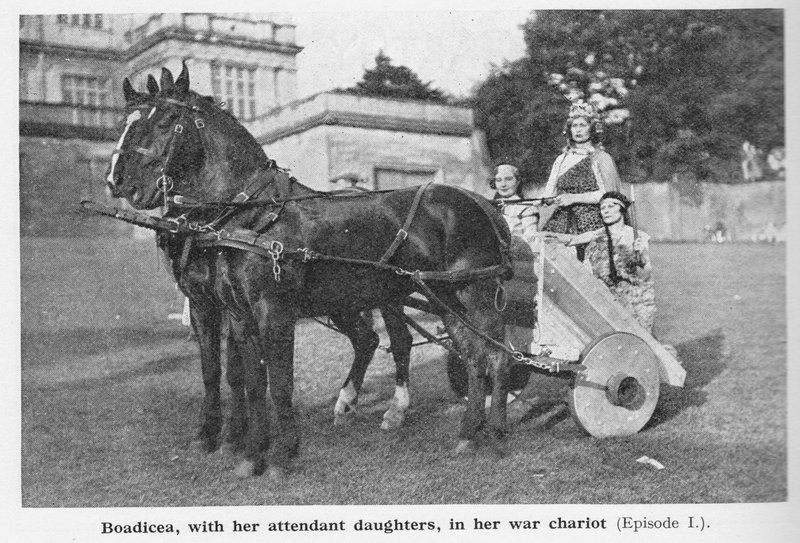

Reflecting the difficult economic context of the region during the pageant, some of the unemployed were given work; the Nottingham Association of Unemployed Workers, for example, made costumes and props for the pageant - including a Roman chariot, market stalls, and a throne for Henry II. On the one hand, this may have been a philanthropic gesture. But it could also have been a necessity; at first, support for the pageant was slow to develop in the city. A letter to the Nottingham Guardian in January 1935 proclaimed: ‘Sir, your appeal on behalf of the Pageant is opportune for it has become obvious that up to the present the public have shown little interest in it.’ Around three months later the picture had seemingly changed, with the same newspaper reporting that Nottingham had caught the ‘Jubilee Spirit’ - with some parts in the pageant being doubled or even tripled out of demand. There was also more general national interest, with the Tamworth Herald, Swindon Advertiser, London Standard and Sheffield Independent all featuring articles about the upcoming event. The Nottingham Evening Post even reported that the role of Boadicea received 400 applications ‘from all parts of the country’, with 20 being interviewed.

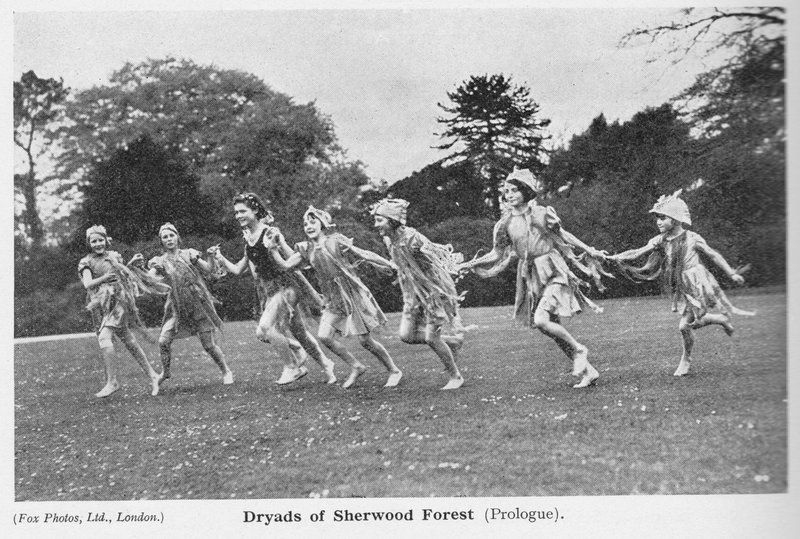

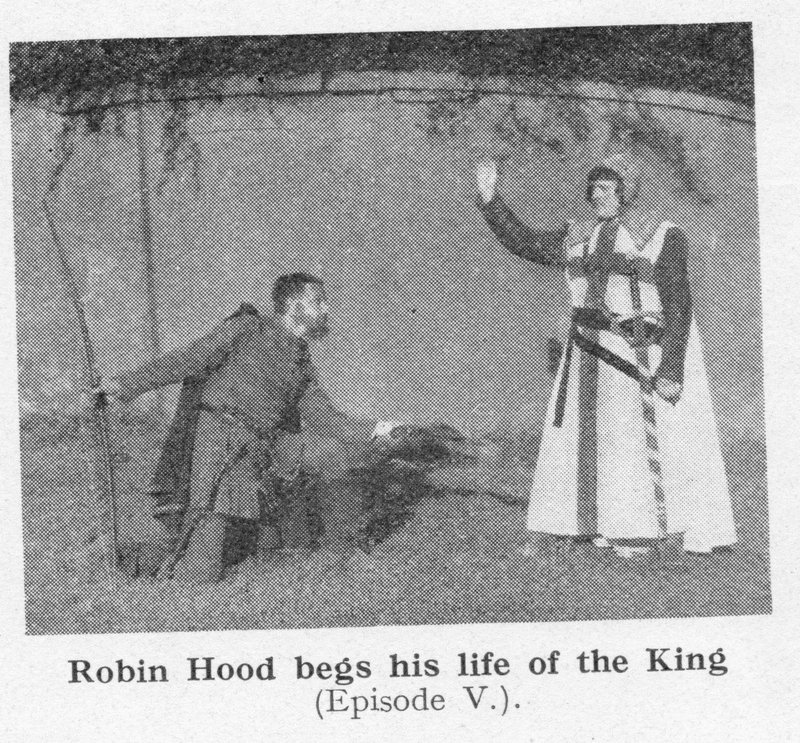

Instead of depicting a linear narrative showing just the rise of Nottingham, episodes involving the city’s hinterland were also devised. They featured famous historical figures in not just Nottingham, but several county places as well. Monck claimed to have developed the practice of historical pageantry without influence from the first pageant-master, Louis Napoleon Parker. But, in terms of themes and style, he was actually perhaps the most faithful interwar interpreter of Edwardian historical pageantry. He used dialogue extensively; mixed both serious and more light-hearted pageantry; and utilised allegory as a presentational device. At the same time, however, there were some of the artistic flourishes of the more modern pageant-masters, such as Lascelles, that came through especially in scenes that featured the ‘common-folk’ in large crowds. The pageant began, as was common, with an allegorical prologue, where various muses of history instructed local children to watch the portrayal of history. As well as fairies of the field and countryside, ‘gnomes of the mines and factories’ were also portrayed – a nod to the industrial lifeblood of the city. Naturally, being a pageant of Nottinghamshire, Robin Hood and his band of merry men featured in this episode, as well as having a whole episode later in the pageant, set in Sherwood Forest.

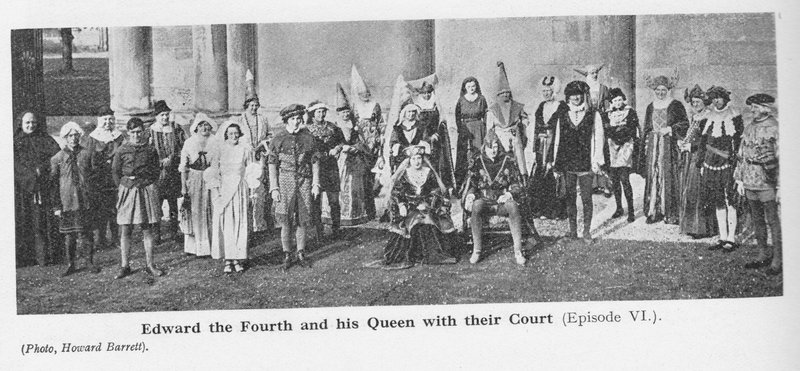

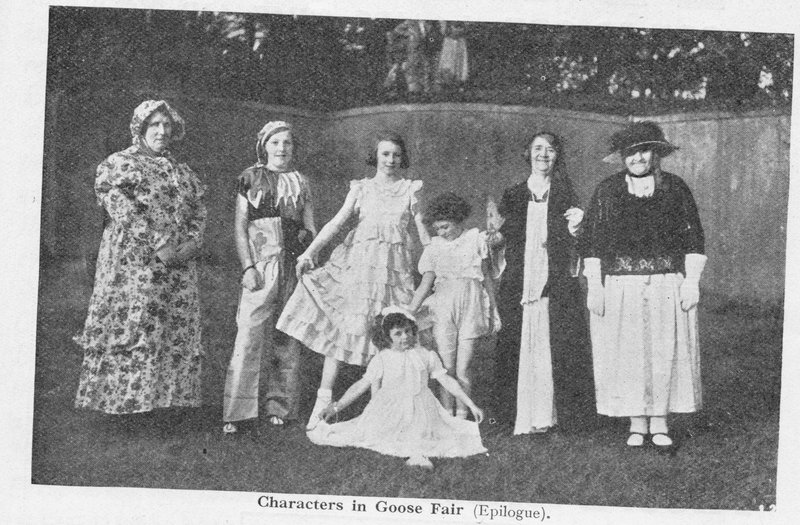

Other episodes were fairly generic pageantry fare, and illustrated several common themes. Firstly, the connection of important figures and events to the life and history of the county (Episode I featured Boadicea’s revolt; Episode II featured Paulinus, Archbishop of York, spreading Christianity; Episode III featured William the Conqueror, giving Nottingham Castle to William Peveril; Episode VI featured Edward IV, bringing the splendour of the Royal court to the city; Episode VII featured Cardinal Wolsey at Southwell Palace; and Episode VIII featured Charles I, Colonel Hutchinson, and Prince Rupert, and the Civil War). Secondly, and in contrast, cultural events of a more local character (most notably Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest, Episode V; the final episode, which showed the locally celebrated Goose Fair; and the epilogue, which introduced historical figures associated with both the industrial and cultural life of the county). The pageant also showed something of the municipal development of the city, by portraying the granting of the city’s first charter in AD 1155 (Episode IV).

Throughout, there was opportunity for grand spectacle and massed movement, with Monck the 6000-strong cast to good effect. Dancing and singing was present in many episodes. According to Monck (in an interview several years later), ‘the central theme of modern pageantry’ was the depiction of the ‘influence of the crowd’, by which he meant ‘the increasing power of the man in the street to organize his life.’ In the context of economic depression, Monck’s ethos likely aimed at creating some local hope and buoyancy, and was a simple-but-effective way of making pageants more relatable to large crowds of urban-industrial workers. This was especially evident in the final Goose Fair scene, which featured no famous faces, and instead concentrated on small incidents of a local and humorous character.

Despite poor weather, the pageant was a huge success. Over the duration of the week, 53600 people paid for admission, and a further 5700 paid to see the Great Carnival Procession. On the County Day, 4000 people were ready at the start of the day to witness the festivities and on Wednesday 12 June it was reported that ‘The departure of the civic party was witnessed by 10000 people who defied the rain and cheered to the echo.’ Public demand meant two extra performances of the pageant were put on the following Tuesday and Wednesday evenings. A very impressive £4000 profit was made to donate to hospitals - largely awarded to Nottingham General Hospital, which received £2215 18s. 4d. The next largest donation was £886 7s. 4d., which went to Nottingham Women’s Hospital; and the smallest was £25, which was given to Workshop and Newark Hospitals. Of the six institutions listed as receiving money, four were in Nottingham. The perceived collective achievement was summed up by Nugent Monck when he said, to all involved, ‘Your efforts have placed Nottingham on the map.’

*All photos kindly provided by Ellie Reid, from the Book of Words, and the Souvenir*