The Pageant of Birmingham 1938

The Birmingham 1938 Civic Pageant was one of the largest pageant ever held in Britain, designed to eclipse civic and national rivals at Runnymede in 1934 and Manchester in 1938. The pageant was the culmination of inter-war pageantry in which the epic scale, and the range and complexity of audio-visual effects, wholly eclipsed the performance itself. Indeed, the Birmingham Pageant was epic in a number of ways, not least its epic financial losses. Despite many failings in its realisation, its huge financial losses, and a hostile press which saw the pageant as preferring sound and fury over substance, the pageant has gone down in folk memory, and its more overblown aspects made a deep and lasting impression on local civic culture.

The main pretext of the pageant was a conjunction with the Royal visit to Birmingham to mark the centenary of the city’s civic charter. This was a meticulously planned day beginning with the arrival of George VI and Queen Elizabeth at Birmingham New Street, their opening of the new Hospital Centre, and a visit to a newly opened Centenary Park. The day would continue with a sixteen-mile long procession through the city, with the route lined with floral displays and symbols of Birmingham’s heraldry. Most notable would be the ‘Spirit of Birmingham’ in the form of a young smith bestriding the City, and holding in his left arm a wrought disc, upon which is embossed a mother and child standing against an oak tree, to signify the birth of art in association with natural beauty’. The Royal couple would then view the pageant accompanied by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain (himself a famous son of Birmingham). In the event, however, things did not quite go to plan: the King was too ill to visit the pageant and the Duke of Gloucester attended on his behalf. In fact, the costs of the Royal visit (paid for by the City Corporation) were only £7466, £2533 less than the £10000 put aside. This was to be the only part of the event which did not run massively over-budget.

The preparation of the pageant encountered many difficulties: ‘some of the scenario was not completed until rehearsals began, while the script of the finale was not completed until a few days before the pageant itself.’ The overall conception was altered a number of times, with an episode on the founding of King Edward’s Grammar School deleted a few months before its performance because it ‘had little dramatic effect.’ Lally demanded some 8000 performers for the Pageant, and the city officials were more than happy to agree to the epic scale. Unfortunately, recruitment for the pageant was slow, particularly in the poorer areas of Edgbaston. Many people were unhappy at the size of the city’s expenditure on the pageant, combined with perceived high prices for admission. Ultimately, the pageant had to recruit volunteers from much further afield across the whole of the Black Country, and it paid nearly £1000 in transporting them to and from rehearsals or paying to accommodate them. Preparations were on a huge scale. The work rooms, attached to enormous warehouses, were employing, five months before the pageant, a mistress of the robes, four designers, six cutters, twenty machinists with sewing machines and irons, and twenty finishers, not to mention the metalworkers and blacksmiths to create real suits of armour for the hundreds of knights who appeared in the Battle of Crecy.

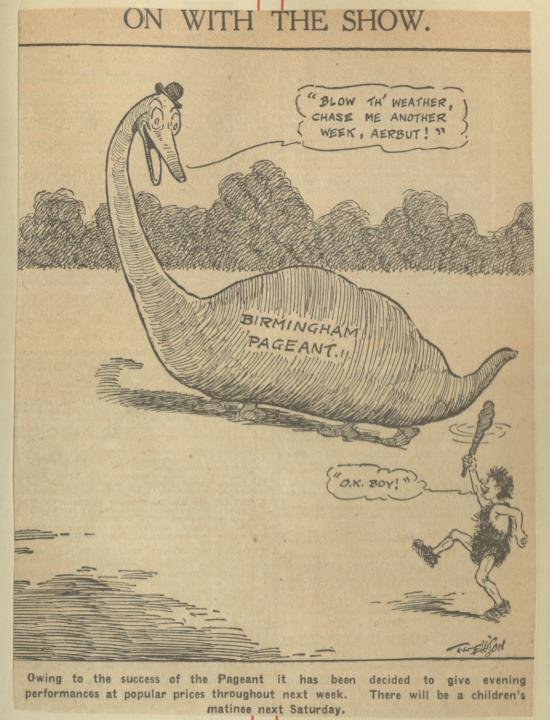

The local opposition towards the pageant’s high-handed attempts to impose civic spirit combined with appalling weather in the weeks running up to the pageant, which severely impeded rehearsals and added many unforeseen costs. The result was low box office takings, as fewer than hoped bought tickets in advance. Rain dogged the first week of the pageant and exacerbated the under-attendance. (The Pageant Committee had considered but then rejected the notion of insuring the pageant against adverse weather.) It was the decision of the pageant to be held over a second week, at greatly reduced ticket prices, which led to the record-breaking audience of 137 545. A cartoon in the Birmingham Mail depicted the famous dinosaur, Egbert, telling his prehistoric nemesis, ‘Blow the weather, chase me another week, Aerbut!’

Egbert and Aerbut

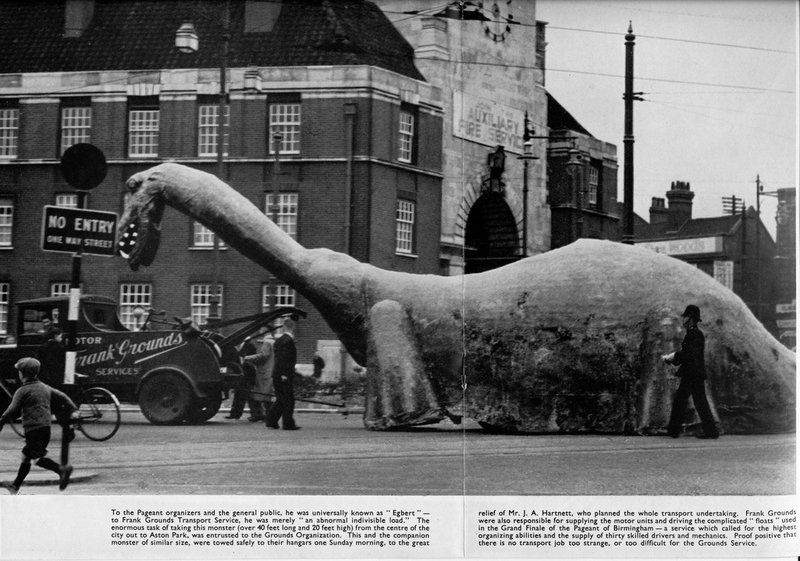

The most visual symbol of this spectacular miscalculation was Egbert the dinosaur, a sixty-foot, smoke-breathing dinosaur, ‘as large as a church’, who anachronistically fought with cavemen in the first scene. Though Egbert was the part of the pageant most fondly remembered, he was criticized at the time as a distracting extravagance, with the Leamington Spa Courier remarking that ‘the introduction of such monsters gives a quite erroneous impression that the pageant is intended to be a burlesque.’ Egbert has ever since remained a popular character in Birmingham’s folk memory and is frequently mentioned on internet forums, with one article entitled ‘Dinosaur Cosplay in the 1930s was Creepy as Hell’.

A key problem was that incredible set pieces tended to eclipse the other scenes, such as the actual establishment of the town by Peter de Bermingham. The third episode recreated the Battle of Crecy, which was a great spectacle, aided by the use of massive floodlighting: ‘No one who ever visits Aston Park this week will ever forget the thrill of the charging horses ridden furiously across the arena. It was an amazing achievement, daring both in conception and execution… There was an amazing incident when one of the “slain” fell off his steed so realistically that an ambulance man rushed to the rescue, to be waved off by the casualty—to the relief of the spectators.’ The Manchester Guardian, whose hostility can only be partially explained by rival civic loyalties, pointed out that there was at best a highly tenuous link between the town and a battle fought on French soil, which was that a local historian had discovered that four percent of the men-at-arms were from Birmingham. The newspaper reported one spectator who was quoted as saying, ‘It is better than a Test match…and look, the English have won.’

The episode’s final scene appeared belatedly to justify Birmingham’s place in the empire as one of its pre-eminent manufacturing centres, which had provided countless inventors, writers, and politicians (depicted in the episode). Whilst this was true, the attempt to represent the continuum of Birmingham’s industrial power, from the early nineteenth century to the present, struck many observers as incongruent, particularly given the prolonged period of recession: The episode was something of ‘an anti-climax. The vast lorries carrying erections symbolising Birmingham’s leading commercial undertakings are more in the tradition of a carnival procession than that of a Pageant…[O]ne found the transition to a display of modern advertising methods not altogether to one’s taste. The two elements do not mix, and there is a complete absence of unifying idea.’ The writer ‘felt that Queen Victoria would have made a better climax’, though was admittedly impressed at the spectacle of the final procession.

The Pageant made a spectacular loss of £11835, despite a massive attendance of 137545. There were many who felt that while the Birmingham Pageant was certainly a financial failure that crippled the city’s finances, it yet succeeded in its aim of raising the city’s profile and boosting civic pride. The Birmingham Post noted that whilst the cost to the city had been dear, ‘At the same time it is felt that the pageant achieved a very great success and was the means of arousing a civic consciousness attracting a considerable amount of attention to Birmingham.’ The Sub-Committee report into its own spectacular failings ended a scathing report with a quotation from the Birmingham Post the previous week: ‘Whatever the deficit, and the reasons for it, perhaps it will be best to regard the Pageant of Birmingham as an adventure that drew the attention of Great Britain to “The Hub of Industrial England” and gave its humblest citizen a civic pride that should endure long after the dead past has reburied its dead.’ In terms of the enduring local interest in the Pageant, this evaluation has proved accurate indeed.

(Egbert in Procession)

Links:

Watch a film of the Pageant on the BFI website