St Albans Pageant 1953: A Masque of the Queens (1953)

Having staged a pageant during the height of Edwardian ‘pageant fever’ in 1907, as well as one of the early post-war pageants in 1948, St Albans did it for the third time during the Coronation celebrations of 1953. This was a larger pageant than the one five years earlier—with more than 1600 performers, well in excess of the 1000 of 1948—but otherwise similar in its organisation and emphasis. The pageant-master, again, was Cyril Swinson, who had been praised for his work in 1948 and who was one of the most prolific pageant-masters of the 1950s, and whose brother Arthur later wrote and produced the St Albans ‘pageant-play’ of 1968. The organisation involved many of the same individuals, including Alderman J.M. Donaldson, who chaired the executive committee on both occasions. As in 1907 and 1948, the outdoor venue was Verulamium Park, with the cathedral and abbey church providing the impressive backdrop. As in 1948, the organisers applied for exemption from the entertainments tax and established a number of committees to deal with particular aspects of the organisation, ranging from costumes to horses to music.

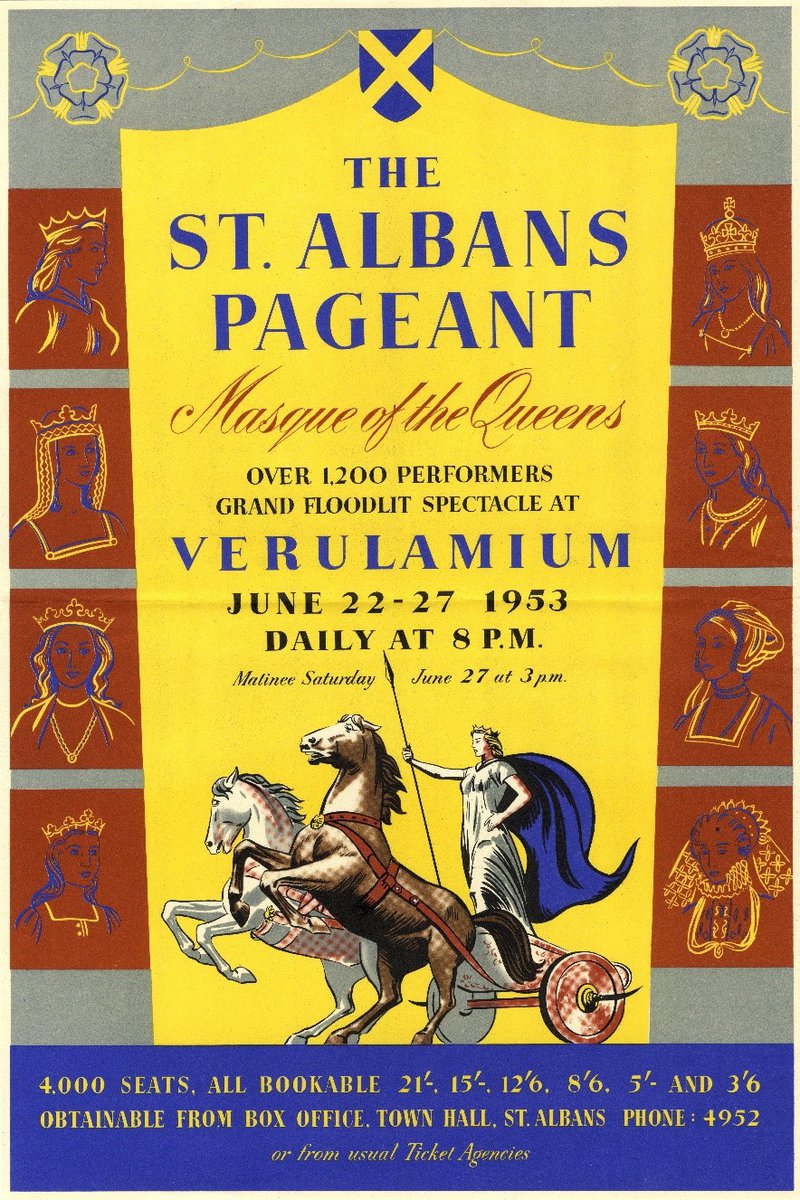

A poster advertising the 1953 St Albans pageant.

Image courtesy of St

Albans Museums

The

pageant was called ‘A Masque of the Queens’, reflecting the occasion of the

Coronation, and each scene depicted a visit of a queen to St Albans, although

perhaps the word ‘visit’ is not appropriate to the Boudicca scene (Episode I).

The theme dictated the periods that could be covered, which meant that, apart

from Boudicca’s revolt, all the episodes were post-Conquest. Some of the scenes

had characters who had appeared in St Albans pageants before, such as Elizabeth

I and the Bacon family of Gorhambury, Henry VI and Queen Margaret, Humphrey

Duke of Gloucester and John and Sarah Churchill, but other features of the

pageant were new. Queen Anne appeared for the first time, as did Anne Boleyn

and various prominent ladies of the Victorian period. Developing a trend that

was already apparent in the inter-war and early post-war periods, there was

more humour and frivolity in the pageant: the ‘comic highlight’, according to

one observer, was the smoke-breathing dragon, which featured in Episode V. The

dragon appears in the surviving film footage of the pageant, and it also

appears to have influenced children’s writer Rosemary Manning, whose novel Dragon in Danger (1959) tells the story

of a dragon who appears in a pageant in ‘St Aubyns’.

St George slaying the pageant dragon in St Albans, 1953.

Image courtesy of Peter

Swinson

The

‘queens’ theme resulted in an elaborate and ambitious costume drama, featuring

a whole gamut of well- and lesser-known historical figures, many of whom were

probably not recognisable to the audiences who came. Swinson skilfully blended

national and local history in his script and scenes, drawing on the importance

of the town and abbey of St Albans in the medieval period and bringing some of

the town’s prominent families and abbots into the episodes, as well as monarchs

from Boudicca to Queen Anne (Queen Victoria, although mentioned, did not

actually appear). He certainly did his research. He wrote in the souvenir

programme: ‘For my sources of information I have drawn upon contemporary

records, and only in Episode 10 have I had to invent the situation. ... For the

other episodes I have ranged from Tacitus and the Abbey Chronicles to such

modern works as the Victoria County History, the [Oxford] Dictionary of

National Biography, Charles Ashdown’s works, and Sir Winston Churchill’s life

of his illustrious ancestor: the Duke of Marlborough.’

Boudica (played by Brenda Swinson) in her scythe-wheeled chariot, with

entourage, in the 1953 St Albans pageant.

Image courtesy of Peter

Swinson.

A lot of effort was made, as always, to recruit participants and spread interest in the pageant. The arrangements occasioned some controversy, particularly when it emerged that—as a cost-saving measure—Swinson planned to use recorded music rather than an orchestra. This led to complaints at a public meeting, held at the town hall in December 1952, but the anticipated cost of recorded music, £200, was only one-fifth of what Swinson estimated a full orchestra would cost. Eventually Swinson and the ‘Master of the Music’, Lewis Covey-Crump, adopted a compromise solution, with a 100-strong choir and a 35-person orchestra, which would in total cost in the range of £250 to £300. In the end, the musical arrangements were ambitious, with some specially written music and a whole range of songs and orchestral pieces used throughout the two-hour performance.

Although

the Coronation was the immediate occasion for the pageant, local patriotism and

civic pride were heavily emphasised. As in 1948, the St Albans ‘pageant hymn’

was sung, this time at both the beginning and the end of the show. This song

remained in the civic consciousness of St Albans for some time and was even

sung at Swinson’s funeral in 1963. Swinson wrote in the local press at the time

of the pageant: ‘I feel it is all to the good to stimulate pride in the city

just now, when it is in danger of becoming a dormitory, or a large disorganized

mass.’ Concerns about the preservation of local history and civic memory were

particularly significant in the context of post-war planning and rapid

population change: St Albans was a designated ‘expansion town’ and saw a large

influx of new residents in this period, while in the following decades its

manufacturing base declined and its commuter population increased. As Mark

Freeman has shown elsewhere, these concerns were shared by pageant organisers

in many post-war towns and cities, resulting in the 1950s in a localism that

was perhaps even more intense than had been seen during the heyday of ‘pageant

fever’. As before, the pageant provided a way to bring the past into the

service of the present in new and distinctive ways. Thus the souvenir programme

(which was also the book of words) included a set of historical notes

significantly entitled ‘Past, Present and Future’. The last section, written by

the city surveyor, envisioned further suburban development, continued

employment in manufacturing industry, and a blend of past and present in the

fabric of the city: ‘[t]he future St Albans will be a pleasant place, retaining

the best of the old combined in a harmonious way with the modern development

and presenting a picture of an English city growing and changing through the

centuries’. Although the preservation of the civic past was an important

element of local politics and culture in the post-war period—Swinson himself

was a founder member of the St Albans Civic Society, established in 1961—the

emphasis here was as much on the future as on the past, and the pageant

reflected a certain degree of confidence in what was to come.

Souvenir

badge from the 1953 pageant.

In St Albans Museums’

collection; photograph by Mark Freeman.

The pageant itself, however, did not live up to expectations. Although it was undoubtedly enjoyed by those who took part in and saw it, it made a financial loss, mostly due to disappointing audiences. Only 17709 people paid to sit in the grandstand across the seven performances, less than two-thirds of the total capacity, although another 1280 sat on the grass for the weekend performances. The overall loss was £1203. 1s. 4d., resulting in a call on the guarantors for 4s. 6d. per pound promised. There had been some heavy expenditure, including £3757 on the grandstand and £1550 on costumes and props, and the total income was just £7900, compared with a projection of £13500. The organisers had tried to learn some lessons from 1948, when there had been too many expensive seats and not enough cheap ones, but this did not bring the hoped-for audiences to the pageant. The organisers’ report blamed the later start time of 8pm, which dissuaded visitors from beyond St Albans (although some special transport was arranged), traffic bottlenecks resulting from a poor layout of the pageant ground, and the ‘strong counter attraction’ of other Coronation activities, which meant that most advertising was done locally. Some of these problems had been foreseen. In March 1953 one member of the committee wrote to Alderman Donaldson with his concerns:

We shall certainly not get the free publicity which we got [in 1948] … We were pioneers, it was a novelty, the country had been starved of pageantry during the war period and more money was available. This time, every town, village and hamlet is having its own celebrations and, therefore, it will not be possible for the press to single out any one collaboration, or they would all expect similar treatment.

This correspondent urged a

smaller, less ambitious pageant, ‘definitely not on the scale of the 1948 one’.

In the event, the 1953 pageant was larger and more expensive and proved to be

the last outdoor pageant that St Albans staged. A smaller indoor ‘pageant play’

was staged at the new City Hall in association with the St Albans Festival in

1968, but there was nothing on scale of 1953 in the city again.

For more details of the 1953 pageant, see the database entry here. See also Mark Freeman, ‘“Splendid Display; Pompous Spectacle”: Historical Pageants in Twentieth-Century Britain’, Social History 38 (2013), 423-55.