The Warwick Pageant of 1906

The success of the Sherborne pageant attracted a good deal of notice, particularly in places with claims to long or illustrious histories. One of these places was the town of Warwick, site of an important castle since the tenth century and famous for its association with the ancient British king Caradoc, the legendary hero Guy of Warwick, Warwick the Kingmaker, and other notable figures. In June 1905, in the context of Parker’s extraordinary success at Sherborne, Edward Hicks, an enterprising Warwick journalist (and author of a book about Caradoc), pounced on a passing suggestion in the Daily Telegraph that Warwick would be an ideal site for a historical pageant. Writing in the Warwick Advertiser, Hicks challenged the town to demonstrate ‘the importance of its place in the national life of the past’. Roused by this patriotic appeal, local opinion quickly mobilised behind the idea. The Lord Mayor declared his support, as did the heads of the town’s secondary schools, and by the beginning of July a provisional pageant committee had been established. This was soon followed by the establishment of an executive committee based in Jury Street, at the building now known as Pageant House, and the launching of a fund – based on public subscriptions and guarantees – to underwrite the costs of the event. In view of the Sherborne example, the executive committee resolved to acquire Parker’s services as Pageant Master, and by the end of September he had indicated his willingness to act. By mid-October, a town meeting had formally resolved to go ahead.

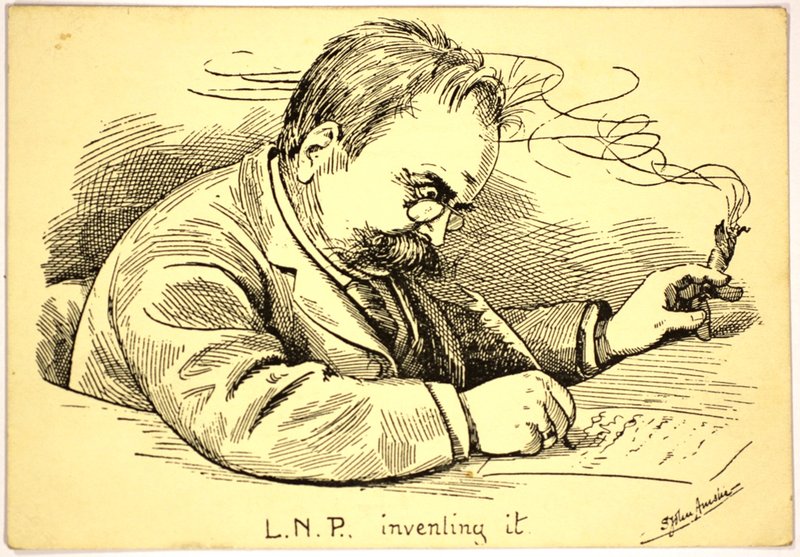

[Postcard: “L.N.P. Inventing it”: Warwick County Record Office CR367/35/10. Credit: S. John Austin]

Thereafter, things moved quickly. Indeed they had to do so after it had been announced in early November that the performances would be held in the week beginning 2 July, leaving just eight months to get things ready (it is hard to imagine such a large-scale event being organized so quickly in the twenty-first century!). The pageanteers, led by the seemingly tireless Parker, spent the winter and spring in a flurry of publicity and organisational activities. Tens of thousands of pamphlets promoting the Pageant were distributed; articles about the event were published in the local and national press; episodes were devised and music was commissioned; books of words and souvenir programmes were printed; and a Ladies Committee marshalled the sewing prowess of three hundred Warwick women, who working in 14 teams produced 1400 costumes. Indeed, following Parker’s usual practice, almost everything used in the pageant was of local manufacture, and it seems that many Warwick men and women spent a great deal of their spare time that winter making weapons, banners and other props.

By late May, the first rehearsals were being performed, cast members being summoned by means of special postcards issued from the meticulously well-organised headquarters office at Pageant House. There were two hundred speaking parts! On 21 June a full dress rehearsal was put on, for which cheap tickets were offered, and to which journalists and photographers were invited. Cheap tickets aimed at the town poor and schoolchildren were also sold for the rehearsals in the week before 2 July. These proved very popular – on one day three times as many people as could fit in the grandstand turned up – and their popularity was doubtless in large part due to the fact that seats for the pageant performances proper were priced at levels well beyond the reach of many poor families (the cheapest seats, of which there were not many, were 3/6; the next cheapest were 5s.)

Pageant week got underway on Sunday 1 July with a special service at St. Mary’s Collegiate Church, preached by the Bishop of Bristol. Special services were also held in other parish churches in the town. This was in line with Parker’s ideas about pageants; he was always very insistent that pageant week celebrations should commence with special church services. And indeed, the religious content of the Warwick Pageant is striking, perhaps affording evidence that claims of the secularisation of early twentieth-century British society have been exaggerated. The antiquity of Christian belief in Warwick is hammered home in the early parts of the pageant. Episode I shows Caractacus saving a child from pagan sacrifice, and then later returning to Britain to preach the word of God; episode II has the legendary British king Gwar [Gwdyr] found a church at Warwick. This is followed by the godly Ethelfleda’s conversion of captured Danes, and two episodes featuring the return of Warwick heroes from the Crusades, one of whom (Roger de Newburgh [Beaumont]) demonstrates his faith by founding a hospital in honour of the Templars, and establishing St. Mary’s as a collegiate church.

Aside from its religious content, another notable feature of the pageant – common to many early pageants – was the avoidance of any coverage of the English Civil War. This reflected the organizers’ sensitivity that doing so would undermine the patriotic and community-buttressing agenda of the event. For a similar reason, perhaps, the Reformation was also ignored. Indeed, with the exception of the long-distant Wars of the Roses (handled via Shakespeare), which unlike the Reformation did not map onto any very serious contemporary divisions, events suggestive of disharmony are not present in the pageant at all.

Local history and tradition loomed large in the pageant episodes. The legend of Guy of Warwick and his slaying of the terrifying Dun Cow was too dramatic a story to leave out, and proved particularly popular. Special attention was given to the construction of the monster’s head. After Guy had told how he had severed it from the Dun Cow’s body in mortal combat, the thing was wheeled into the arena on a special trolley, its eyes still rolling and its nostrils breathing smoke.

[Postcard: Rejoicings at the death of the Dun Cow": Warwick Record Office: CR2409/8/10]

Real-life town benefactors and notables such as Thomas Oken and John Fisher were also celebrated, of course, as well as the earls of Warwick and their families. Present-day notables were honoured too: it is significant that the final episode, set in 1694, features an appearance by a member of the Greville family, who would hold the title to the Earldom of Warwick after its fourth creation in 1759. But throughout the pageant, the original intention that local history be fused to the larger narratives of the English national past is everywhere apparent; through means of its pageant, Warwick, a small provincial town by 1906, sought to assert its importance to the national life of the past (Parker called the place ‘the Clapham Junction of English history’). This is shown not least by the prominence of British kings and queens, and also through the presence of William Shakespeare and Warwick the Kingmaker. One highlight was the arrival of queen Elizabeth I in a magnificent state coach.

[Postcard: "Queen Elizabeth Arrives": Warwick Record Office: CR2409/8/9]

The pageant was accounted a great success, and did much to raise the temperature of the ‘pageant fever’ developing in the wake of the Sherborne performance. With the exception of that on the opening day, all performances seem to have been sold out, with visitors coming long distances (some travelled from the United States) to see the show. Warwick itself was en fete throughout pageant week. Businesses closed early, the pageant properties (including the impressive head of the monstrous Dun Cow) were displayed in the streets of the towns, and the local press carried very extensive coverage of the performances and associated events. These latter were numerous, and ranged from a celebratory civic luncheon held by the mayor, to an exhibition of watercolours of ‘Old Warwick’ and ‘Shakespeare’s Country’ at Warwick Castle, to a competition inviting members of the public to guess the weight of ‘exceptionally large pieces of coal’.

Warwick hosted other pageants after 1906, notably those of 1930 and 1953; and more recently still one was staged in 1996. But the pageant of 1906 was the largest and most elaborate of all held in the town, and its traces are still very visible in the place today. Pageant House and Gardens remain as physical memorials to the event, the former now housing Warwick Registration Office and the latter being very popular with locals (not least as a venue for wedding day photographs). Furthermore, the pageant continues to function as a focus for civic pride. In the newly-refurbished tourist information centre the visitor can watch film footage from the pageant as part of a display devoted to the event, which is described as a great success not only in meeting the challenge set by the Sherborne example and generating funds for the purchase of Pageant House and Gardens, but as evidence that, even in 1906, Warwick ‘knew how to entertain its guests’.