Lions Led by Donkeys, Pageants made by Patriots

As we enter the centenary year of the First World War a fresh battle is taking place in the pages of the national press. Predictably wading in first, with about as much subtlety as a German whiz-bang, was Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Education. According to Gove all this talk of the complex geo-political situation pre-1914, the accusation that the war was a shambles presided over by an out-of-touch elite, or the possibility that perhaps not everyone wanted to fight to the death, is just the ‘Left wing’ guff of ‘academics all too happy to feed those myths by attacking Britain’s role in the conflict.’ Thoughtful rebukes quickly came from a variety of sources. Shadow Education Secretary and historian Tristram Hunt accused Gove of rewriting history, while also pointing out that much of the left back in 1914 actually supported the war; Professor Richard Evans has deconstructed Gove’s claim that the war was ‘just’ and fought for freedom; and even Tony Robinson, of Blackadder fame, has jumped in to defend the necessity of a varied interpretation of history.

In the subtext of these debates two important questions still remain: what is a fitting commemoration for a horrific conflict in which millions lost their lives, and where does the concept of patriotism fit within the act of remembrance? I have a confession: as much as it pains me, on a variety of levels, to say that Michael Gove *might* have a *small* point… he does. In his original piece for the Daily Mail, he said:

"Our understanding of the war has been overlaid by misunderstandings, and misrepresentations which reflect an, at best, ambiguous attitude to this country and, at worst, an unhappy compulsion on the part of some to denigrate virtues such as patriotism, honour and courage."

Though he may be guilty of Evans’ characterisation of a “tub-thumping” jingoist, and is undoubtedly twisting a complex historiographical debate for his own purposes, it does seems to be the case that the genuine patriotism felt by some contemporaries is missing in public debates about commemoration. In our rush to condemn Gove and other politicians appropriating the past for more cynical present-day purposes, we run the risk ourselves of obscuring the multi-faceted nature of popular reactions to the First World War 100 years ago.

Of course, there was warranted regret and shock after the events of the War: the famous poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon was only the emotive surface of a wider current of pacifism and anti-militaristic feeling in the inter-war period. Yet, within popular patriotism, there was still a space for a more reflective articulation of national identity and togetherness. Historical pageantry was one way that contemporaries attempted to engage with this difficult issue and, though theatrical, hammy, and at times bizarre, it had an inherent level of emotion yet nuance that is missing from some of the arguments now taking place.

Historical pageants were huge events involving thousands of amateur actors, watched by even larger crowds of spectators. Almost totally the work of volunteers, who not only performed but also made dresses and publicised the event, they projected moral interpretations of the past directly into the uncertainty of the present. Pre-First World War pageants invariably stopped well before the present day, instead concentrating on less contentious regal, civic, and ecclesiastical histories. Yet in the post-war decades, some pageants – such as the Historical Pageant of Manchester in 1926 or the Empire Day Pageant in 1932, took the bold decision to dramatise the First World War.

One notable effort was the Greenwich Night Pageant in 1933, a mammoth spectacle of 2500 performers, taking place in the grounds of the Old Royal Naval College. According to the pageant-master, the nationalistic Arthur Bryant, its goal was to ‘take the mind off the worries of everyday life’, ‘kindle enthusiasm and knit up a community’ and enable ‘differences of creed and politics’ to be laid aside. For Bryant these feelings were very real; as his biographer Julia Stapleton has argued, dramatic spectacle was but a servant in the awakening of a higher and more powerful patriotism. The theme of sacrifice ran clearly throughout the pageant, reaching its zenith in the terrifying and novel visualisation of the horror of the First World War in the final scene:

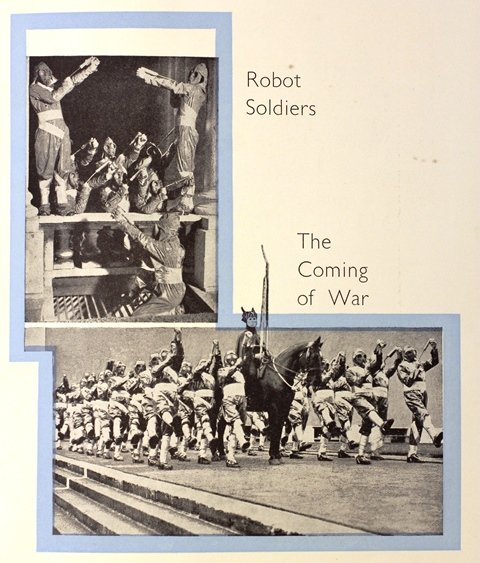

"…the sound of a tolling bell is heard, the movement of the dark waters increases and weird noises, suggesting tempest, and far voices calling, break the silence. Gradually these increase, lighting and thunder are joined with them, and, as the sea vanishes into darkness, the back screen is half lit by ominous flames and shadows. Then the noises die away, to be succeeded by a strange and haunting march, and a beam of light reveals a company of armed men marching across the top of the steps. Their helmets are of steel and their faces are pointed and photophorescent, while their uniforms gleam with slime. Their motions are not those of humans, but of rigid automata. At first the light picks out only them; then another beam reveals their leader, who is Death, with a skull head and white floating robe and riding a horse. So they pass across the stage, till the light suddenly leaves them. For one second there is darkness; then in one blinding flash of light, the whole stage seems to shake with sound. Amid the thunder of artillery and the rattle of machine guns, and the shrieking sound of flying steel, screen, colonnades and buildings are lit by running flame. For some thirty seconds, all Hell seems to have broken loose, as sirens add to the inferno of noise; then the flames grow quieter and the sound of battle with them, till a ray of light illumines a single figure standing erect at the top of the steps. He is in naval uniform and is blowing a bugle, and as he blows, the notes of his call strike high across the din and banish it. Then notes and figure are dimmed and the roadway below is flooded with light, and filled with a crowd in the clothes of August, 1914. They pass across the stage, surrounding and following a company of Naval Reservists, led by the Town Band, marching to the station on Sunday, August 2nd. The cheerful strains of brass band and the cheering, confident crowd provide a complete contrast to the previous scene…."

Pictures of the Greenwich Night Pageant (1933). Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 1.

The theme of military might and sacrifice was clearly forefront in the mind of the pageant president, Admiral Domvile – an anti-Semite interned during the Second World War for his pro-Nazi views. Giving his approval of Bryant’s plans for the War scene, he expressed his ‘unpleasant feeling that anything martial is not popular in Greenwich.’ This, he believed, was a bad thing: ‘the sooner they learn to become a bit more martial again, the better.’ Though Bryant agreed, seeing military heritage as a legitimate object of national pride, he was no warmonger – evinced by his naive pro-appeasement in the 1930s. While showing pride in the actions of the military, the pageant also tried to show the ‘hell’ and confusion of war. Sombre incorporation of remembrance, in a commemorative rather than jingoistic fashion, was one way that the rituals of popular imperialism evolved after peace - the lions, rather than the donkeys, providing the focus of attention.

Praised almost universally in the press, attended by around 100,000 people, and making a profit, the Greenwich Night Pageant shows us that the concept of patriotism after the War was not simple or universal. Popular, thoughtful, and emphasising community and loss instead of victory and pride, many could respectfully remember the dead while recognising the patriotic impulse it served - we could perhaps learn a lesson from this past as the battle lines of commemoration are drawn in 2014.

‘Michael Gove blasts “Blackadder myths” about the First World War spread by television sit-coms and left-wing academics’ - http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2532923/Michael-Gove-blasts-Blackadder-myths-First-World-War-spread-television-sit-coms-left-wing-academics.html#ixzz2ppXTruYe

‘Richard J Evans: Michael Gove shows his ignorance of history – again’ - http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/06/richard-evans-michael-gove-history-education

Sir Tony Robinson hits back at Michael Gove's first world war comments - http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/05/tony-robinson-michael-gove-blackadder-first-world-war

Tristram Hunt, ‘Michael Gove, using history for politicking is tawdry’ - http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jan/04/first-world-war-michael-gove-left-bashing-history

Pictures of the Greenwich Night Pageant (London, 1933).

Book of the Pageant, Greenwich, 1933 (London, 1933).

Julia Stapleton, Sir Arthur Bryant and National History in Twentieth-Century Britain (2005).

Letter from Admiral Domvile to Arthur Bryant, 8th February 1933 in BRYANT C22, File 1. At the Liddell Hart Military Archives of King’s College London.