Searching for Norman Carey

Many of the pageant-masters we are researching in this project left large and easily accessible archives, along with reams of newspaper articles and photographs associated with each event they staged. Often working at the large town or city level, producers like Frank Lascelles, Louis Napoleon Parker, and Gwen Lally were known figures associated with the world of theatre. Bold, charismatic, and frequently eccentric, they seemed aware of the importance of projecting a captivating and confident personality. They became minor celebrities, interviewed in the press and featured on postcards and other ephemera. Other pageant-masters were known only locally, and even then were often not figures of any great repute. While some had ‘tread the boards’ or produced minor shows, most were more likely to be enthusiastic reverends, historians, or minor civic figures, enthused primarily with a love of locality. After the pageant had finished, it drifted out of public representation, the smallest often leaving only a book of words and a couple of articles in the local rag, often taking with it the pageant-master. Yet even the producers of such ephemeral pageants could have fascinating backstories.

‘A Dream of Old Bulwell’ was a small indoor pageant-play that took place in 1929 at the Bulwell Olympia, a struggling local theatre. Beyond a small piece in the Nottingham Evening Post, and a thin souvenir programme, it has left very little evidence of its staging. It was masterminded by the Rev. Stanley M. Wheeler, who acted as author, arranger, and pageant-master, the profits (if there were any) going to the Bulwell Parish Church Organ Renovation Fund and the Bulwell Nursing Association. Reflecting the strength of local industry, the patrons were predominately made up of businessmen and industrialists, and there was an episode dedicated to showing staple industries like pottery, lace, and coal. If Wheeler was the architect of the pageant, however, the second-pageant master, Norman Carey, was its intriguing poster-boy.

Stanley M. Wheeler, A Dream of Old Bulwell : Historical Pageant Presented in 12 Episodes (1929), p. 4. By courtesy of the Local Studies Library, Nottingham City Libraries & Information Service.

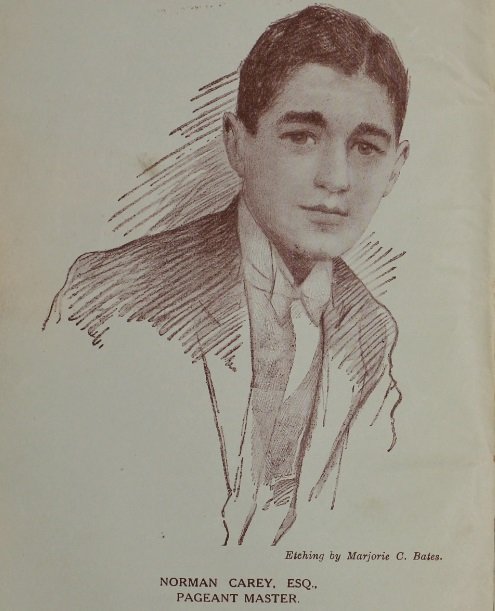

In the souvenir programme he was depicted in a striking portrait sketch by local notable artist Marjorie C. Bates. Dressed in formal wear, he seems mischievous and noticeably younger than his actual age of 29. Part of an old and established Nottingham family, his father, W.H. Carey, was a former city council member, Sheriff of Nottingham, and founder of the large employer Bulwell Finishing Company in the 1880s, as well as a main patron of the pageant. His son was seemingly a bit of a tearaway. Earlier in the same year of ‘A Dream of Old Bulwell’ he was summoned to court for declining to move his car when requested by a policeman. Allegedly, when told by the officer that he would be reported if he refused, he replied ‘“Oh, that’s all right. My father is a J.P., and I will phone Colonel Lemon [the Chief Constable of the County] and report you for not moving these three [other] cars.’ Already having claimed that he had obstructed the road ‘for ten minutes while the Prince of Wales was going up in an aeroplane’ during a regal visit, he further ‘surprised’ the magistrates when asked if he had anything to say to the bench: “Nothing, except to ask why he [the officer] does not carry a pencil. He had to borrow mine to take down my name and address.’ The judge was left bemused but not amused, and fined the impertinent Carey.

Only four years later Norman Carey died at the age of 33, tragically before the death of his elderly father, who had already seen his first son killed in the First World War. 150 employees of the Bulwell Finishing Company attended Norman’s funeral and over 60 wreaths were given, but no information was given on the cause of death for the seemingly popular figure. As is often the case with minor pageant masters he has left the researcher with more tantalising speculations than firm conclusions. How did he get the gig as pageant-master? Was it through his powerful father, perhaps pushed as a way to control his cheeky son? To what extent did he even organise the pageant, or was he maybe a mere assistant to the main brain of Wheeler? And how, more invasively, did he come to die so young? We’ll probably never know the answers to these questions; he remains only faintly visible as one example of the many interesting characters associated with historical pageants.

Tom Hulme