Warwick: Pageant-Mad

I’m sitting in a pub near Warwick train station, ruminating on my pageant-related research efforts in the town’s record office over a pint of beer. My ruminations are being interrupted by some awful piped music (Chris de Burgh’s ‘Lady in Red’!), but the place is a certainly cut above those usually found near railway stations. It’s a cavernous black-and-white affair, dating it seems from the fifteenth century. There does seem to be a fair few older half-timbered buildings in Warwick, despite the fire of 1694 that destroyed many of them. I saw some fine examples down Mill Street, a cobbled medieval lane leading to the river Avon, in the course of a fish-and-chip-fuelled lunchtime search for a good view of Warwick Castle.

As evident from the town’s built environment, the past is still very present in Warwick. There’s the Castle, of course. Everyone knows about the Castle. But humbler places are also celebrated, such as Thomas Oken’s house, another fine Tudor building and now a quaint tea room. Thomas Oken was one of Warwick’s most generous benefactors, on his death in 1573 giving away much of his fortune for the benefit of the poor. His philanthropy was much celebrated in the 1906 Warwick pageant, but it’s not forgotten today; a charitable organization bearing his name still exists. People here seem keen on their history. The last time I visited Warwick, with Tom, the man in the fish and chip shop told us about the regular ‘Victorian Evening’ held in the town centre, something of a highpoint in the calendar of civic festivities (the locals dress up, the tourist office makes a big deal of it too). This time, the fish-and-chip man told me an anecdote about the great fire of Warwick. Apparently, as the fire was spreading the town gaoler told his prisoners that he could not countenance their perishing in the flames before they had had ample time to reflect on their misdeeds, so he let them free – having extracted a promise that they would return to finish their sentences. He didn’t see any of them again, so the story goes.

Warwick’s tradition of historical pageantry is another marker of the place’s engagement with the past. Some of this tradition lives on in the martial and other re-enactments at Warwick Castle, whose grounds and park hosted all of Warwick’s pageants (even today, modern-day tourists at the castle will see the site of the 1906 pageant identified as the ‘Pageant Field’, a space which is often used for concerts and other entertainments). It also lives on – and this is an equally good example – in the popular dressing-up and festivities of the town’s Victorian extravaganza held every November.

The rear of Pageant House - headquarters of the Pageant in 1906, bought after with the profit and presented to the town

The Pageant Gardens

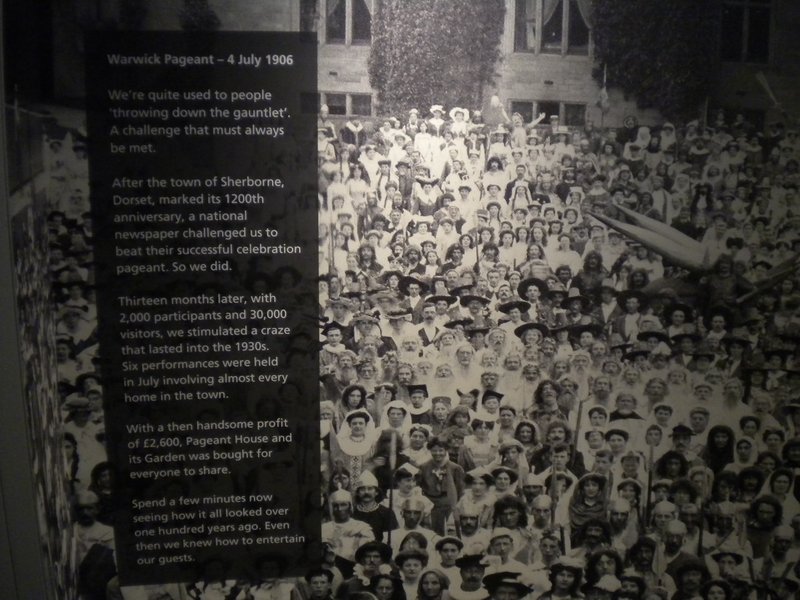

Four major pageants were staged in Warwick over the course of the twentieth century, the latest in 1996. Indeed, it early succumbed to the craze, being second off the mark, after Sherborne in 1905, to stage an historical pageant – inspired in part by the challenge of a newspaper journalist that Warwick move to ‘demonstrate the importance of its place in the national life of the past’. This story has passed into the town’s official memory. Indeed it is re-told in the spanking new tourist information centre in Warwick. On a panel behind a screen where a clip from the 1906 pageant plays in a continuous loop, the visitor is told

We’re quite used to people throwing down the gauntlet… After the town of Sherborne, Dorset, marked its 1200th anniversary, a national newspaper [the Daily Telegraph, no less] challenged us to beat their successful celebration pageant. So we did.

Even today, it seems the 1906 pageant can be mobilised as a source of local pride.

Warwick Tourist Information Centre

Warwick Tourist Information Centre

Of course, this is gratifying to the scholar of

historical pageants seeking to demonstrate the ‘relevance’ of her/his

research: ‘we still care about pageants, you know’, I can now say to

sceptics… and I can mention the Warwick Tourist Information display as

an example of this. But the Warwick example also shows another aspect of

the longer term impact of the pageant fever. Pageants didn’t just

promote feelings of local (and national) patriotism; neither were they

simply fun; they could create quite significant sites of memory for

local communities. The Headquarters of the officers of the 1906 pageant

were located in a handsome house on Jury Street, in the centre of

Warwick, which now directly adjoins the Tourist Information Centre. This

house is now known as ‘Pageant House’; it was bought with the proceeds

of the pageant; owned by the town, it is a popular venue for weddings.

Its garden, also bought with pageant-generated funds and named ‘Pageant

Garden’, is a pleasant public open space. It is a popular lunch-hour

resort for Warwick shop and office-workers. The legacy of

twentieth-century historical pageantry lives on in modern-day Warwick.

Paul Readman